HOW TO MAKE A NEGRO CHRISTIAN IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

In the late 1500’s, Wahunsenacawh, the mamanatowick (Paramount Chief) of the Powhatan people created a confederacy of 30 groups, each with a weroance (leader, commander) representing between 14,000 and 21,000 eastern Algonquian speaking peoples in an area of about 8,000 square miles called Tsencommacah (“Densely inhabited land”) inhabited by the Paspahegh people . Today that area is called Richmond, Virginia. In 1585, Wahunsenacawh discovered English immigrants illegally crossed the Tsencommacah border. As part of a scheme by Walter Raleigh and Richard Hakluyt to export England’s growing number of unemployed in order to create new markets and increase the riches of the British Crown while at the same time establishing a military base to attack Spanish settlements, Queen Elizabeth supported this early group of immigrants. To sell the idea, the true purpose was concealed and spreading Christianity to the Powhatan was promoted. By 1590, the settlement was found deserted. In 1607, the English immigrants set up a squatter’s camp along the north bank of the Powhatan River. Conflicts began immediately. The English immigrants fired gun shots as soon as they arrived. Within two weeks, the English immigrants had already killed Paspahegh people. By 1610, Illegal English immigration continued. Wahunsenacawh said, “Your coming is not for trade, but to invade my people and possess my country…Having seen the death of all my people thrice… I know the difference of peace and were better than any other Country.” Under the instruction of the London Company, Thomas Gates set out to “Christianize” the Powhatan Confederacy. Starting with the Kecoughtan people, Gates lured the Indians into the open by means of music-and-dance and then slaughtered them, initiating the First Anglo-Powhatan War in June. Nine years later, in 1619, THE HUMAN TRAFFICKING OF AFRICAN PEOPLE BEGAN WITH TWENTY PEOPLE BROUGHT TO TSENCOMMACAH BY SHAREHOLDERS OF THE VIRGINIA COMPANY OF LONDON. Within five years, more than 4,000 English immigrants illegally crossed into Tsencommacah. The British Government took direct control of the illegal English squatter’s camps and designated them a royal colony of England. By 1636 Colonial North America's slave trade begins when the first American slave carrier, Desire, is built and launched in Massachusetts. Massachusetts becomes the first colony to legalize slavery in 1641 and two years later, the New England Confederation of Plymouth, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Haven adopts a fugitive slave law. Finally, in 1660, Charles II, King of England, orders the Council of Foreign Plantations to devise strategies for converting slaves and servants to Christianity.

Terry M. Turner and Paige Patterson write in God’s Amazing Grace: Reconciling Four Centuries of African American Marriages and Families,

“The salvation of slaves was an attempt by Great Britain, a Christian country, to follow the Great Commission. English laws determined their mission was to fulfill the Gospel mandate of Matt 28:20 among all people. Consequently, the afflictions suffered in slavery by early African-American marriages and families were initiated by the motivation to convert them to Christianity.

The following are instructions that were issued by King Charles to the Council of Foreign Plantations: ‘And you are to consider how much of the Natives or such as are purchased by you from other parts to be servants or slaves my be best invited to the Christian Faith, and be made capable of being baptized thereunto, it being to the honor of our Crown and of the Protestant Religion that all persons in any of our Dominions should be taught the knowledge of God, and be made acquainted with the mysteries of Salvation.’ [Siphiwe note: salvation is not a concept within traditional African spirituality since no one was born in “sin”].

However, the conventional belief among slaveholders in the Americas was that the salvation of any male or female slave granted them their freedom. This was in opposition to the King of England’s request to keep the Great Commission and evangelize Africans and Indians. This misunderstanding created a need to protect the institution of slavery.

The colonies rejected the legislation of the council and King Charles. One of the arguments offered in defense of the modern slave trade was the false idea that an African American was an infidel. This belief justified the enslavement of the African Americans. In the ancient world, all men were considered equally capable of becoming slaves, but with the conversion of the people of Northern Europe to Christianity, the custom of enslaving prisoners of war gradually ceased between Christian nations. Although between Christians and Mohammedans, the practice of enslaving war prisoners continued.

During this era, the concept of African-Americans as chattel became ingrained in the minds of European-Americans, both Christians and non-Christians. As a result, state laws legislated Black people as inferior, which promoted the idea they deserved slavery over Christianity. Additionally, it was believed that to be a Christian, one needed to complete a catechism; therefore, they must be able to read and understand the Bible. As a result, colonial states passed laws that forbade slaves from reading and writing, imposing hefty fines towards violators. South Carolina’s Act of 1740 legislated that, because chattel could not be educated, African- Americans could not be educated. This law stated that African-Americans were human, but were to be held in chattel-hood and not receive an education:

‘Whereas, the having slaves taught to write, or suffering them to be employed in writing, may be attended with great Inconveniences; Be it enacted that all and every person and persons whatsoever, who shall hereafter teach or cause any slave or slaves to be taught to write or shall use or employ any slave as a scribe, in any manner of writing whatsoever, hereafter taught to write, every such person or persons shall, for every such offense, forfeit the sum of one hundred pounds, current money.’

By 1667, Negro labor had become so profitable that Virginia enacted a law that declared that ‘the conferring of baptism doth not alter the condition of the person as to his bondage or freedom. Masters, thus freed from the risk of losing their property, could more carefully endeavor the propagation of Christianity. In spite of the early church requirement for reading as a method for catechism, slaves soon found they could have a relationship with Christ regardless of the traditional way of becoming a Christian. Edward Baptist discovered that slaves found Christ through spiritual emotionalism in Christianity that also served as a link to their African religious experiences:

‘Enslaved people born in Africa - still in the late 1700’s a significant percentage of Chesapeake slaves - came from a part of the world where it was common for [spirits] to throw people on the ground, to breathe in and through them, to ride worshippers’ spirits and remake their lives. These new converts demonstrated the same intensity of conversion . . . .

The real measure of salvation is a spiritually converted heart to the principles of Christianity, regardless of a person’s ability to read and write. . . . During slavery, Christian doctrines were used to justify slavery and oppression. . . . Yet, enslaved people continued to flock to churches, ‘even if ministers turned their backs on them. . . . Those who became converted Christians found mental escape from the hardships of slavery . . . .Although their inability to read and write left them with little or no theological understanding, they had an excess of spiritual songs that were sung to help them endure their suffering.”

DR. REVEREND CHARLES COLCOCK JONES AND THE RELIGIOUS INSTRUCTION OF THE NEGROES

In her article, Voodoo: The Religious Practices of Southern Slaves in America, Mamaissii Vivian Dansi Hounon writes

“Contrary to popular belief, the Africans enslaved [in] America were not Christians. . . .the builders of this . . . nation were practitioners of the various African religions . . . . These spiritual practices of the Africans enslaved in America, have their ancestral origins. . . . directly from Dahomey, Nigeria, Senegal, Ghana, The Congo and other West African nations. . . . Though some forms of westernized Christianity made its way to many West African nations prior to the trans-Atlantic voyages, IT EFFECTED LITTLE INROADS into the lives of the millions of traditionalists Africans captured and enslaved in America.

In his book, Religion of the Slaves, Professor Terry Matthews writes,

“In the early decades of the nineteenth century, Christianity had made LITTLE OR NO IN-ROADS among Blacks for fear that they might take literally such narratives as the exodus . . . Various plantation owners expressed the concern that ‘the superstitions brought from Africa have not been wholly laid aside . . . .’[This was] often cited as evidence that the plantation slave refused to abandon African paganism for American Christianity. . . . Long before their contact with whites, Africans were a strongly religious and deeply spiritual people. . . . Indeed, the religion of modern Blacks represents a RELATIVELY MODERN DEVELOPMENT that dates back to the last several decades before slavery was brought to an end.”

Finally, Carter G. Woodson notes,

“The student of this phase of history will naturally inquire as to the actual results from all of these efforts to promote the progress of Christianity among these people. Here we are at a loss for facts as to the early period; but after 1890 when the first census of Negro churches was taken, we have some very informing statistics: and although the general census of 1900 took no account of such statistics, the United States Bureau of the Census took a special census of religious institutions in 1906, basing its report upon returns received from the local organizations themselves. . . . . Comparing these statistics of 1906 with those of 1890, one sees the rapid growth of the Negro church. Although the Negro population increased only 26.1 per cent during these sixteen years, the number of church organizations increased 56.7 per cent; the number of communicants, 37.8 per cent; the number of edifices, 47.9 per cent; the seating capacity, 54.1 per cent; and the value of the church property, 112.7 per cent.”

To the question, why? Why did we become Christians, again, Kamau Makesi-Tehuti writes in his book How To Make A Negro Christian,

“Reconnecting to our main theme, we weren’t Christians, but we became Christians. Why? Why were/are the Afrikan systems of spirituality so fearful to the caucasoids? If we all believe in a Higher Power, a Higher Force, a Supreme Deity with many different names - as we profess so profusely today - then why did/do caucasoids expend so much energy, time, manpower and resources to covert and spiritually conquer Afrikan spiritual expressions? . . . .

First and foremost - power and control. Caucasoids did not/can never fully understand our spiritual systems. . . . Back during the time of this main thesis, infiltration and co-optation was not the strategy of the day. - total banishment and destruction was, since they couldn’t understand our traditions. ALL things historically that caucasoids cannot elicit power over and cannot enact control on, must be destroyed or at best pushed into obscurity.

Secondly . . . some caucasoids knew something was up when we would bear our drums and dance in certain ways. . . . .caucasoids nonetheless feared the Afrikan language, drums and dancing, banned them and killed violators. Afrikan spiritual undercurrents were the root of most of the enslaved Afrikan rebellions.

‘. . . it was the sorcerer, the native-born Angolan, Gullah Jack at the occasion of the Denmark Vessey conspiracies in South Carolina (1822). [A] . . . .religious exercise anointed the bloody Nat Turner raids in Virginia in 1831; similarly, the conjuring ‘root man’ was blamed for fomenting mid-nineteenth century conspiracies and revolts in North Carolina, Mississippi and Louisiana (Suttles, 98-99). The connections between some kind of secretive. . . . religious exercises and violent rebellions seem fundamental to understanding the progressive history of exploited groups in the America. Slaves revived or tried to revive the old African observances under the amused or unknowing eye of plantation authority, they bound themselves in discipline to rites . . . it is only the beginning, a preface, to active, violent rebellion. For now, through the medium of his religion, the slaves ‘colonized’ self (his slave mentality) was disassociated and the slaves willfully strove to destroy the material and human trappings of the plantation authority around him.’

So we started out Afrikan traditionalists. Afrikan reality was banned and on the surface beaten out of us. Christianity then filled, however poorly, our spiritual void. After the start of the 1900’s, our Theological Misorientation: The belief in, allegiance to, or practice of a theology, religion-based ideology or an y aspects thereof that are incongruous with a) Afrocentricity (as a Black Social Theory), b) Afrikan History, and c) traditional Afrikan cosmology (e.g. harmony with nature, respect for and incorporation of the natural order inherent in the cosmos, spiritual and divine essence as the nature of the original human being, etc. . . .) increased exponentially - partly due to fear, not wanting the reprisals from caucasoid society and partly due to a lot of surface-level similarities between our innate ontology and the foreign imposed system.

Caucasoids had major debates as whether or not to ‘christianize their slaves.’

‘Stung by the effective charge of the abolitionists that the reactionary legislation of the South consigned the Negroes to heathenism, slaveholders considering themselves Christians, felt that some semblance of the religious instruction of these degraded people should be devised. It was difficult, however, to figure out exactly how the teaching of religion to slaves could be made successful and at the same time square with the prohibitory measures of the South. For this reason many masters made no effort to find a way out of the predicament. Others with a higher sense of duty brought forward a scheme of oral instruction in Christian truth or of religion without letters. The word instruction thereafter signified among the southerners a procedure quite different from what the term meant in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when Negroes were taught to read and write that they might learn the truth for themselves (Woodson, 109).

Enter Dr. Reverend Charles Colcok Jones.

‘In the early decades of the nineteenth century, Christianity had made little or no in-roads among blacks for fear that they might take literally such narratives as the Exodus. But as this ‘crisis of fear’ spread across the South, suddenly rather impressive efforts were made to address the ‘needs’ of the souls of black folk. These were well organized evangelistic endeavors, particularly in those areas with large plantations. Congregations stepped up their appeals, and refined their approaches to African-Americans. Preachers and planters alike urged them to fill the gallerys, and special seating that was set aside for these honored guests. Some owners were even motivated to build ‘praise houses’ on their land, and recruited black preachers to proclaim the Lord’s name (as long -of course- as a white foreman was present to monitor things so that they did not get out of hand). Large slaveholders like the Rev Chales Colcok Jones worked to comprise a Christian primer for slaves to instill teachings that were designed as a response to the portents of revolution, and to serve as preventive measures to any insurrection.’

Lastly, here is an excerpt of what Dr. Carter G. Woodson had to say about him in his grossly under-read & under-appreciated prelude to the Miseducation of the Negro . . . :

‘Prominent among the southerners who endeavored to readjust their policy of enlightening the Black population, were Bishop William Meade, Bishop William Capers, and Rev. C.C. Jones . . . The most striking example of this class of workers was the Rev. C.C. Jones, a minister of the Presbyterian Church. Educated at Princeton . . . . and located in Georgia where he could study the situation as it was, Jones became not a theorist but a worker. . . . Meeting the argument of those who feared the insubordination of Negroes, Jones thought that the gospel would do more for the obedience of slaves and the peace of the community than weapons of war. He asserted that the very effort of the masters to instruct their slaves created a strong bond of union between them and their masters. History, he believed, showed that the direct way of exposing the slaves to acts of insubordination was to leave them in ignorance and superstition to the care of their own religion. To disprove the falsity of the charge that literary instruction given in Neau’s school in New York was the cause of a rising of slaves in 1709, he produced evidence that it was due to their opposition to becoming Christians. the rebellions in South Carolina from 1730 to 1739, he maintained, were fomented by the Spaniards in St. Augustine. The upheaval in New York in 1741 was not due to any plot resulting from the instruction of Negroes in religion, but rather to a delusion on the part of the Whites. The rebellions in Camden in 1816 and in Charleston in 1822 were not exceptions to the rule. He conceded that the Southampton Insurrection in Virginia in 1831 originated under the color of religion. It was pointed out however, that this very act itself was a proof that Negroes left to work out their own salvation, had fallen victims to ‘ignorant and misguided teachers’ like Nat Turner. Such undesirable leaders, thought he, would never have had the opportunity to do mischief, if the masters had taken it upon themselves to instruct their slaves. He asserted that no large number of slaves well instructed in the Christian religion and taken into the churches directed by White men had ever been found guilty of taking part in servile insurrections. . . .

. . . ‘his [the Negro} instruction must be an entirely different thing from the training of the Cuacasian,’ in regard to whom ‘the term education had widely different significations.’ For this reason these defenders believed that instead of giving the Negro systematic instruction he should be placed in the best position possible for the development of his imitative powers - ‘to call into action that peculiar capacity for copying the habits, mental and moral, of the superior race.’ . . .

Seeing even in the policy of religious instruction nothing but danger to the position of the slave States, certain southerners opposed it under all circumstances. Some masters feared that verbal instruction would increase the desire of slave to learn. Such teaching might develop into a progressive system of improvement, which, without any special effort in that direction, would follow in the natural order of things. Timorous persons believed that slaves thus favored would neglect their duties and embrace seasons of religious worship for originating and executing plans for insubordination and villainy. They thought, too, that missionaries from the fee States would thereby be afforded an opportunity to come South and inculcate doctrines subversive of the interests and safety of that section. It would then be only a matter of time before the movement would receive such an impetus that it would dissolve the relations of society as then constituted and revolutionize the civil institutions of the South. . . Directing their efforts thereafter toward mere verbal teaching religious workers depended upon the memory of the slave to retain sufficient of the truths and principles expounded to effect his conversion. Pamphlets, hymn books, and catechisms especially adapted to the work were written by churchmen, and placed in the hands of discreet missionaries acceptable to the slaveholders. Among other publications of this kind were Dr. Capers’s Short Catechism for the Use of Colored Members on Trial in the Methodist Episcopal Church in South Carolina.; A Catechism to be Used by Teachers in the Religious Instruction of Persons of Color in the Episcopal Church of South Carolina; Dr. Palmer’s Catechism; Rev John Mine’s Catechism; and C.C. Jones’s Catechism of Scripture,’ Doctrine and Practice Designed for the Original Instruction of Colored People. . . .These extracts were to ‘be read to them on proper occasions by any member of the family’.

Here should be noted the remarks of Nubia Kai from the University of Maryland discussing her book, Kuma Malinke Historiography: Sundiata Keita to Almamy Samori Toure:

“First of all, in the traditional precolonial era, griots were the principle political advisors to kings, chiefs and other high government officials. They were the mediators in international, national and local disputes. They served as ambassadors and diplomats to neighboring countries. They were the chief judicial advisors and advisors of national defense. They were also the officiators of rites of passage ceremonies, naming ceremonies, puberty rights, marriage, naming ceremonies, funerals, as well as, national inaugurations, harvest festivals, religious festivals, sporting events and other national holidays. They negotiated marriage and dowry arrangements between the families of the bride and groom. They were foremost historians, archivists, genealogists, social and cultural anthropologists, musicians and dramatic performers. Training of both male and female griots began at an early age in a peripatetic fashion through close association with their parents and of other family members who were also griots. By the time a griot child reaches adulthood, they have already learned and absorbed a good deal of Mandinka cultural history. Then they may travel widely to learn the local histories of specific regions of the empire and become apprentices of master griots where they may study anywhere from 10 to 20 years. By the time a griot reaches the last stage of initiation achieving the title of [foreign words spoken] "master of the word" they have a mass a phenomenal amount of very detailed knowledge of every aspect of the Mandinka culture, society, history, politics, art, genealogy, and in most cases have mastered a musical instrument or instruments, elocution, singing, dancing and dramatic performance. They have the repositories of history with a repertoire that can fill a library. The astonishing amount of information that the griot's stores in his or her brain corroborates the disarming fact that human beings use only 10% of their brain capacity. For the griots seem use a much larger percent and confirm the singly infinite capacity of the human brain to a mass knowledge. The griots then are far more than storytellers. The use storytelling techniques and devices in their explication of history, yet that skill is a drop in the bucket of a multifaceted range of skills at expertise and numerous professions. The musician, performer, genealogist, historian are in inseparable in Mandinka historiography. The intellectual and esthetic are inseparable. In a culture where there is no separation between the sacred and the profane, the individual and the collective community, the corporal and spiritual worlds, the historical artistic paradigm is only a reflection of the way art is integrated into the daily life of the people. History to the Mandinka griot is a form of divine revelation; a sacred text that provides human beings with a spiritual ethical map on how to arrive by degrees to their initial state of perfection. Since life in this cosmological scheme is sacred, the recording of social and cultural life is also sacred, thus, the histories in traditional cultures are denoted as sacred histories. The most important event in history, in Mali's history, in any history, according to the griot [foreign name spoken] who the picture you have there and who I dedicated the book to, is the birth of a child for when a child is born a miniature universe is born, hence ego that is the ego that we see in the genealogical charts, the individual is the center of the world and the center of history. How does a Mandinka griot accomplish the task of infusing history into the souls of every Malian citizen? The answer lies in a historiography rooted in a correspondent cosmogony and a deployment of esthetic devices designed to engage the body simultaneously at an intellectual, emotional and spiritual level. Drama, ritual and art play a prominent role in the daily life of traditional African society and a special role in enlivening, interpreting and transmitting history so that histories powers of transformation are actualized. . . .

Mythic symbolism attempts to explain the spiritual nature of men and women and their inextricable connection to universal order. In traditional cultures, myths, legends, epics are regarded as real history while fairytales, animal [inaudible] tales are generally categorized as fictional. In the modern world, the extreme methodology of Aristotelian logic combined with social Darwinism relegated myth to the fantastic fictions of the infantile primitive mind. Nevertheless, and despite the intellectual hubris that generated the disfigurement of myth, there was an undeniable consensus regarding its transformational power and peculiar ability to shape and transmute consciousness among some of the most influential religious scholars and psychologists, Mircea Eliade, Bachofen, Carl Jung,[inaudible], Sigmund Freud, W.T. Stevenson and Joseph Campbell turned a psychoanalytical eye on mid and formulated at least a precise explanation of this functionality. The idea that myths are invented in order to rationalize and explain human existence was radically challenged once scholars isolated and carefully observed the cause effect relationship of myth and consciousness. Joseph Campbell, one of the foremost scholars of mythology defines for functions of living myths and their ritual enactments. "The first is what I have called the mystical function to awaken and maintain in the individual a sense of all and gratitude in relation to the mystery dimension of the universe not so that he lives in fear of it but so that he recognizes that he participates in it since the mystery of its being is the mystery of his own deep being as well. The second function of mythology is to offer an image of the universe that will be in accord with the knowledge of the time, the sciences and fields of action, of the folk to whom the mythology is addressed. The third function of the living mythology is to validate, support and imprint the norms of a given specific moral order that namely of the society in which the individual is to live. And the fourth is to guide him, stage by stage in health, strength and harmony of spirit through the whole foreseeable course of a useful life." And that is from Joseph Campbell. . . .

Historical myths record history as it actually occurs though they may be embellished with extended metaphors, hyperboles, parables, proverbs, imagery, symbolism and philosophical analysis. In the epic, the narrative is usually built around the life and deeds of the hero. The circumstances of his or her birth, childhood, trials, obstacles, triumphs and their impact on the course of history. Epics even more than creation myths, are constructed to personalize experience through the vicarious revelation of the hero who's acts epitomize the most cherished human principles; faith, courage, integrity, generosity, compassion, loyalty, intelligence. Through these virtues the hero is able to [inaudible] all opposition and obstacles and achieve a personal and public victory. Often the monomythic journey is a national parable explaining the philosophical and ethical ideas of the society through the life and character of the culture hero. . . . The finite and the infinite, man's mortality and immortality are brought into conflict with each other through the hero's action but the two worlds, the material and spiritual also overlap and the conflicts are resolved through him. . . . In Mandinka society, every social ceremonial whether secular or religious gave rise to colorful, flamboyant and elaborate theatrical performances that involved the entire community and lasted for days or weeks. As [foreign name spoken] noted, everything in them is displayed and performed. Social practices are in a state of permanent dramatization. Ritual drama permeates the society on a daily basis and infuses its members with an experiential sense of history, culture, morality and spirituality. History, culture, politics, and social practice are consistently explicated through multiple forms of dramatic performance; masquerade, theaters, spoken, drama, dance, theater, dramatize [inaudible], and civic and sacred rituals. The epic of Sundiata and many other epics popular among the Mandinka are reenacted in all these theatrical forms. Griots primarily account Mali's history through dramatized narratives. The written word holds a secondary place in their historiography. Why? Because the world was created through the word and history is transmitted through the creative word, the spoken word, thus, history in the Mandinka language is called Kuma the word or word force. The primacy and preference of an oral dissertation of history in a culture that has two written scripts; they have the Mandinka script and the Arabic script but there is still a preference for using the spoken word. It's predicated on the power of the spoken word which contains and abundance of inyama [assumed spelling]. Inyama means a vital force or a vital energy and this vital force and vital energy is contained in the spoken word at much greater level than it is in the written word. So, it pervades and effectively impacts consciousness more than a written text. That's why they prefer to use the spoken word. So, the inyama force that comes from the spoken word instills in audience the mystical function of language so that they know and understand the history exponentially . . . “

Now, the implications of the African cultures prior to the coming of the Christians as outlined above by professor Nubia Kai reveal the profoundest damage and is the key to understanding the effects caused by Reverend Charles Colcock Jones’ Religious Instruction of the Negroes. What was Reverend Jones’ plan?

“They are an ignorant and wicked people, from the oldest to the youngest. Hence, instruction should be committed to them all, and communicated intelligibly. And that it may be impressed upon their memories, and good order promoted amongst them, it should be communicated frequently and at stated intervals of time.

The plan is this. The Planters form themselves into a voluntary association, and take the religious instruction of the colored population into their own hands. And in this way: - As many of the association as feel themselves called to the work, shall become teachers. An Executive Committee is to regulate the operations of the Society, to establish regular stations, both for instruction during the week and on the Sabbath, and to appoint teachers who shall punctually attend to their respective charges, and communicate instruction altogether orally, and - in as systematic and intelligible a manner as possible, embracing all the principles of the Christian religion as understood by orthodox Protestants, and carefully avoiding all points of doctrine that separate different religious denominations. . . . The only difficulty in the execution of this plan, is the procurement of a sufficient number of efficient teachers. . . . “

Here, we see that Reverend Jones was proposing to use the tradition form of oral instruction used by Afrikan griots. Specifically, Reverend Jones, in 1847, stated,

“The instruction must necessarily be communicated in a catechetical way, and with a few exceptions, the multitude of children and youth do not read. This is particularly the fact with those who live in the country. Let the teacher ask the question and repeat the answer; and explain it; and then continue asking the question until the answer is committed to memory, the scholars answering all . . . .The negroes are fond of singing, and it is a matter of much importance to their improvement and interest in the school; that hymns and psalms of a suitable character be taught. . . . These hymns and psalms will be sung by them in their religious meetings, and while they are engaged in their daily duties; and they will gradually be substituted for many songs and hymns, which they are in the habit of using, for the want of something better. . . . At the close, let the superintendent review the school on the lesson and hymns of the day, and explain and apply them; the object being not only to covey the form of sound words, but the substance and power also. Frequent reviews should by no means be omitted. . . . Take the following order of exercises, and it will about consume the time mentioned: - open with singing; read a portion of Holy Scripture - pray; after prayer, let the school repeat the Lord’s prayer, the creed, the commandments, select verses of Scripture; teach the hymn or a portion of it, which the school is learning, and making the school rise, teach, for a short time, the tune with the humn; review the last lesson - sing again - teach the lesson in the catechism for the day - give explanation and make an application; this should be done by each teacher privately to his class, and then by the superintendent to the whole school - and dismiss with or without prayer, and a dismission hymn or doxology. . . . Happy then shall we be, if we can increase the spirit of obedience in our Servants. . . . Happy shall we be if we can . . . . deliver their Masters from the pecuniary loss . . . consequent upon their negligence and crime. . . .There never will be a better state of things until the Negroes are better instructed in religion.”

And what would be the benefits of such religious instruction to the Negro? According to Reverend Jones:

1) There will be a better understanding of the mutual relations of Master and Servant;

2) There will be GREATER SUBORDINATION and a decrease of crime amongst the Negroes;

3) Much unpleasant discipline will be saved to the Churches;

4) The Church and Society at large will be benefitted;

5) The Souls of our Servants will be saved and,

6) We shall relieve ourselves of great responsibility.

Specifically, Reverend Jones stated that,

“obedience will never be felt and performed to the extent that we desire it, unless we can bottom it on religious principle.. . . It will be noticed that obedience is inculcated as a Christian duty, binding on the Servants, and thus the authority of Masters is supported by considerations drawn from eternity”

John Spencer Basset, writing in 1899 in his book, Slavery in the State of North Carolina, states,

“It was, indeed, in a harsh spirit that the law came at last to regulate the religious relations of the slave. In the beginning, when the slaves were just from barbarism and freedom, it was thought best to forbid them to have churches of their own. But as they became more manageable, this restriction was omitted from the law and the churches went on with their work among the slaves. . . . The change came openly in 1830, when a law was passed by the [North Carolina] General Assembly . . . .It was enacted that no free person or slave should teach a slave to read or write, the use of figures excepted, or give to a slave any book or pamphlet. This law was no doubt intended to meet the danger from the circulation of incendiary literature, which was believed to be imminent; yet it is no less true that it bore directly on the slave’s religious life. It cut him off from the reading of the Bible - a point much insisted on by the agitators of the North - and it forestalled that mental development which was necessary to him in comprehending the Christian life. The only argument made for this law was that if a slave could read he would soon become acquainted with his rights.

A year later a severer blow fell. The Legislature then forbade any slave or free person of color to preach, exhort, or teach ‘in any prayer-meeting or other association for worship where slaves of different families are collected together’ on penalty of receiving not more than thirty-nine lashes.’ The result was to increase the responsibility of the churches of the whites. They were compelled . . . to take on themselves the task of handing down to the slaves religious instruction in such a way that it should be comprehended by their immature minds and should not be too strongly flavored with the bitterness of bondage. With the mandate of the Legislature the churches acquiesced.

As to the preaching of the dominant class to the slaves it always had one element of disadvantage. It seemed to the negro to be given with a view to upholding slavery. As an illustration of this I may introduce the testimony of Lunsford Lane. This slave was the property of a prominent and highly esteemed citizen of Raleigh, N.C. He hired his own time and with his father manufactured smoking tobacco by a secret process. His business grew and at length he bought his own freedom. Later, he opened a wood yard, a grocery store and kept teams for hauling. He at last bought his own home, and had bargained to buy his wife and children for $2500, when the rigors of the law were applied and he was driven from the State. He was intelligent enough to get a clear view of slavery from the slave’s standpoint. He was later a minister, and undoubtedly had the confidence and esteem of some of the leading people of Raleigh, among whom was Governor Morehead. He is a competent witness for the negro. In speaking of the sermons from white preachers he said that the favorite texts were ‘Servants, be obedient to your masters,’ and ‘he that knoweth his master’s will and doth it not shall be beaten with many stripes.’ He adds, ‘Similar passages with but few exceptions formed the basis of most of the public instruction. The first commandment was to obey our masters, and the second was like unto it; to labor as faithfully when they or the overseers were not watching as when they were.’ . . All this was natural. To be a slave was the fundamental fact of the negro’s life. To be a good slave was to obey and to labor. Not to obey and not to labor were, in the master’s eye, the fundamental sins of a slave. . . . [Says Lunsford Lane] ‘There was one hard doctrine to which we as slaves were compelled to listen, which I found difficult to receive. We were often told by the minister how much we owed to God for bringing us over from the benighted shores of Africa and permitting us to listen to the sound of the gospel . . . . ‘ On the other hand, many of the more independent negroes, those who in their hearts never accepted the institution of slavery, were repelled form the white man’s religion . . .

Through the teachings of the church many were enabled to bend in meekness under their bondage and be content with a hopeless lot. There are whites to whom Christianity is still chiefly a burdenbearing affair. Such quietism has a negative value. It saves men from discontent and society from chaos. But it has little positive and constructive value. The idea of social reform which is also associated with the standard of Christian duty was not for the slave.

It should be reminded that the very introduction of Christianity in Africa used this same system of white supervision within the church. Chancellor Williams reminds us that,

“White administration and control of African Christianity was assured by establishing the head of the Church in Lower Egypt (the Patriarch of Alexandria) with power to appoint all bishops in Africa. The bishops appointed were always white or near-white until token appointments of Blacks to lesser posts, such as deacons, had to be made following protests by black church leaders, supported by their kings. . . . for ‘white’ Egyptian control over the churches reflected the same policies that were to follow through the centuries into our own times. No church sponsored theological schools for the training of African clergy. By thus preventing educational opportunities, they could always maintain that the Blacks were simply ‘not qualified’ for this or that high post. In religion, as in every other field, the system deliberately prevented qualification in order to declare the lack of qualification on the part of Blacks in all regions under white control or in all institutions, in this case the Church, over which white power prevailed.”

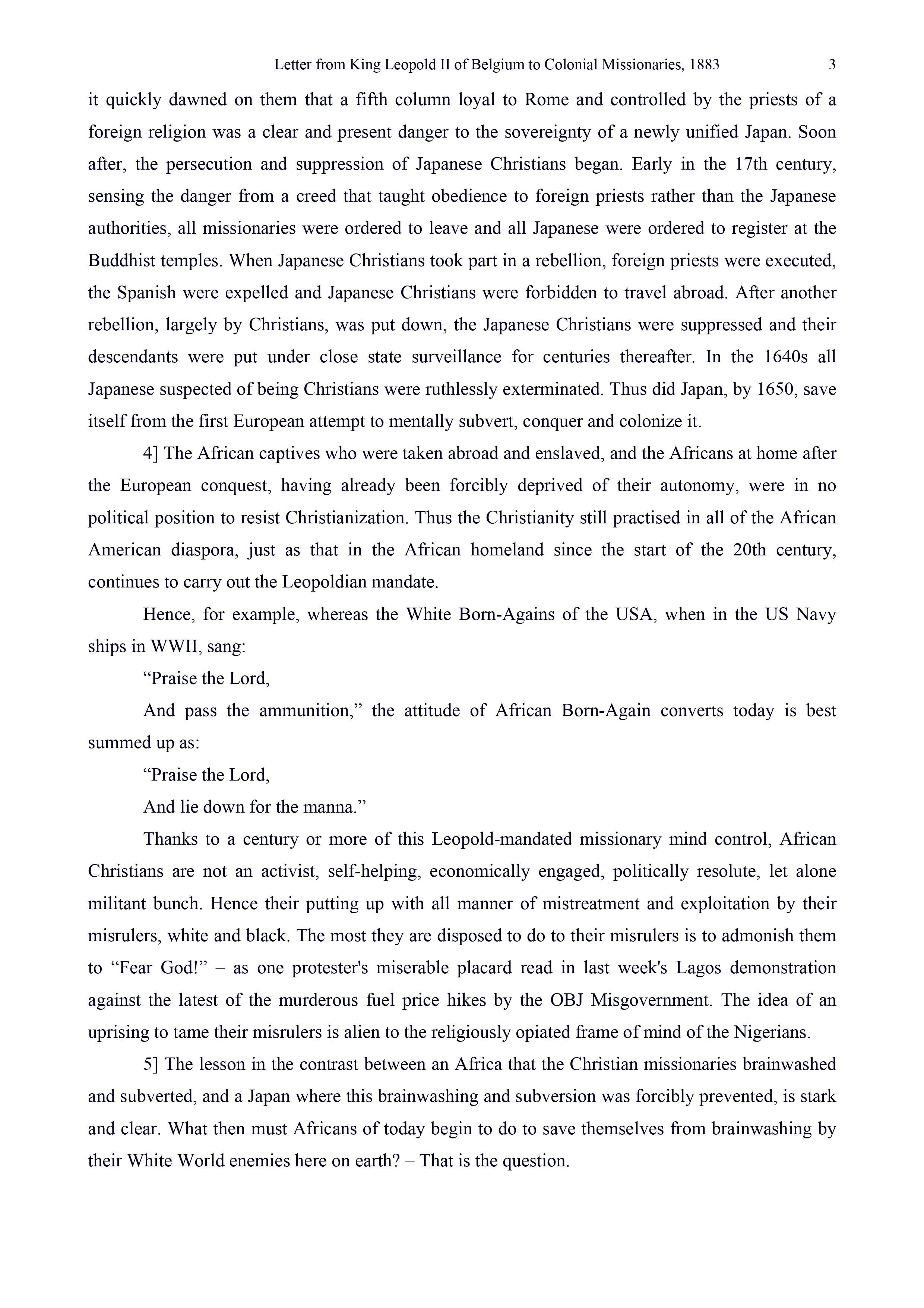

Consider, now the letter from King Leopold II of Belgium to Colonial Missionaries, in 1883, laying out the purpose of their Christian missionaries there: