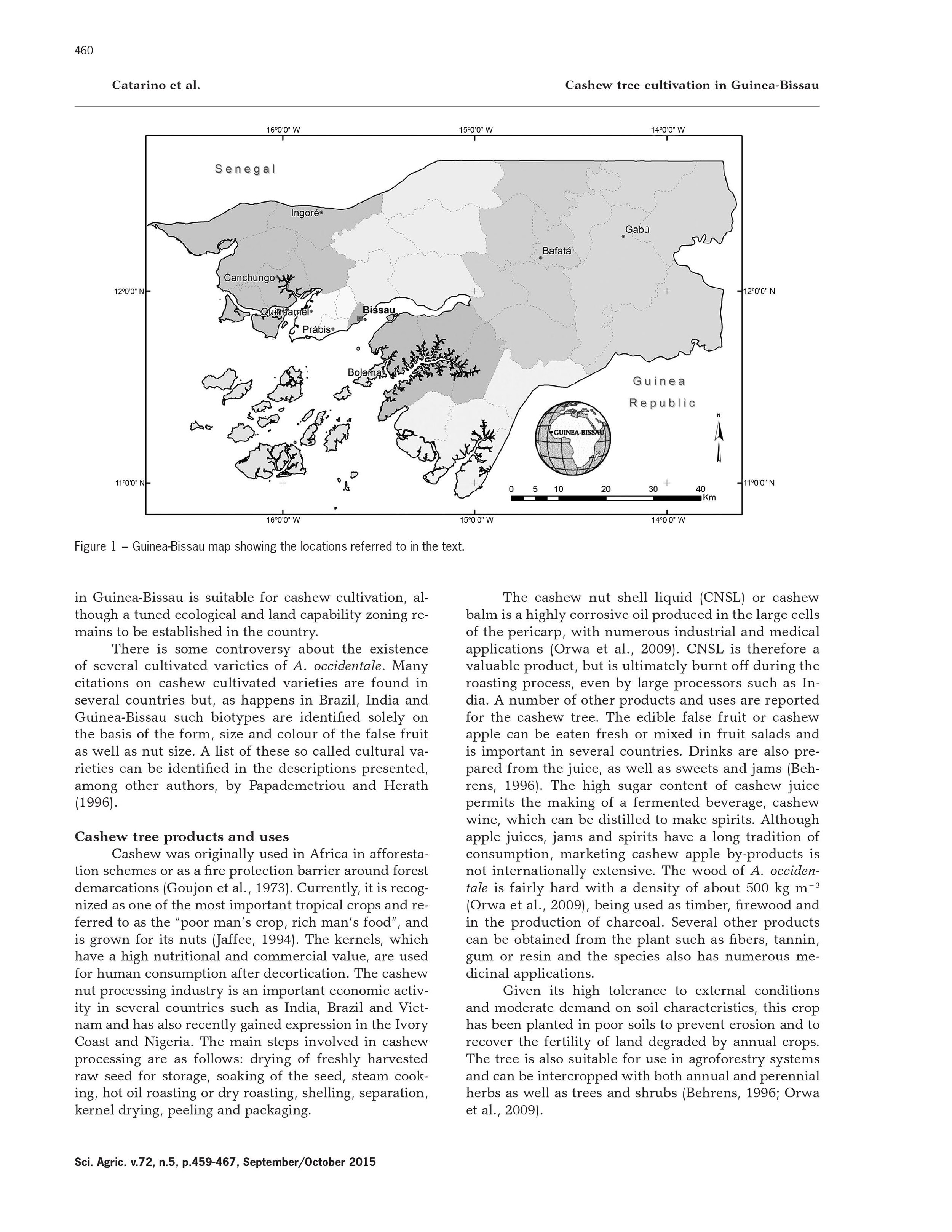

Guinea Bissau is now the second-largest cashew producer in West Africa and in the top five globally. An estimated 223,000 hectares are under cashew cultivation. Today, about 85% of the population depends on cashew farming.

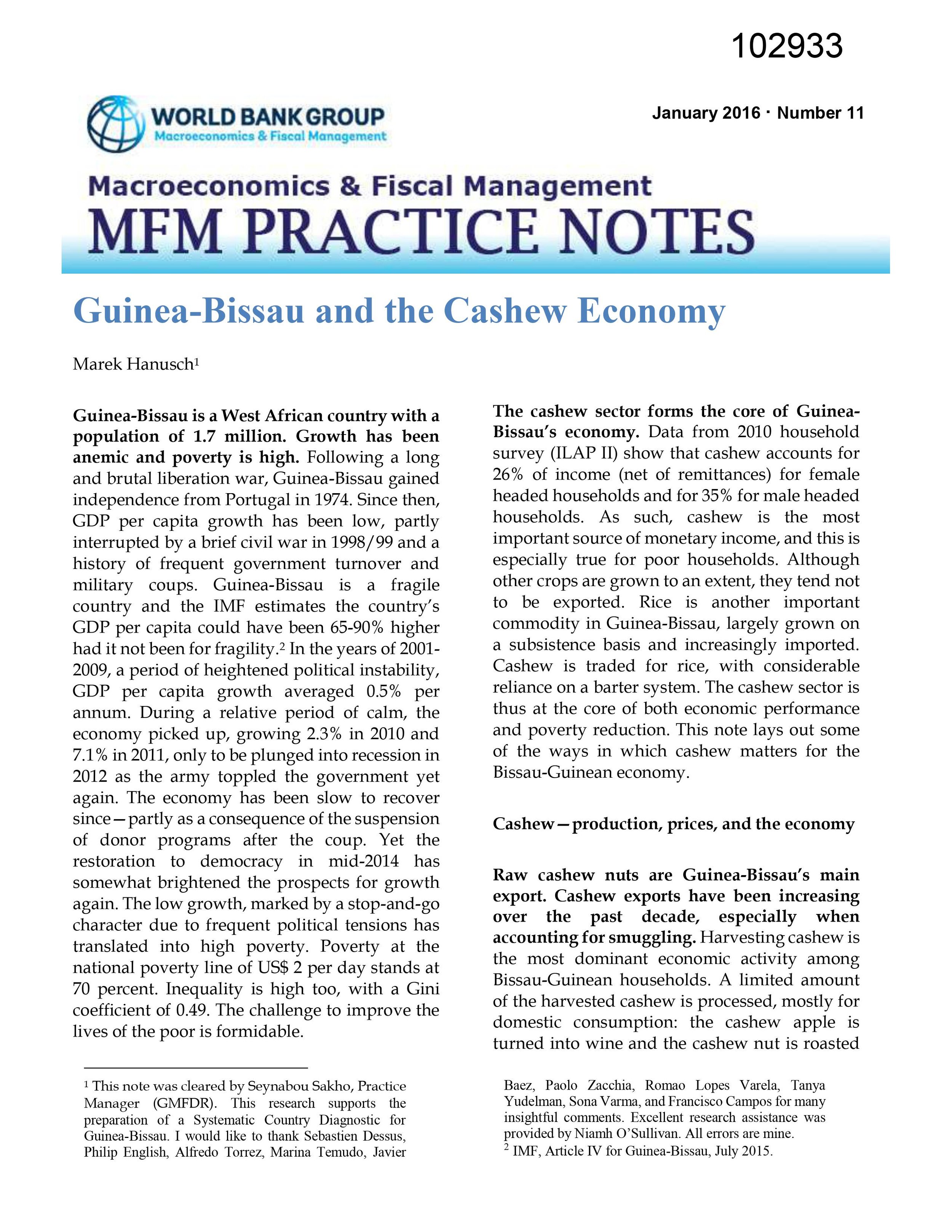

The 2016 Report of the World Bank Macroeconomic and Fiscal Management (MEM) Practice Notes for Guinea Bissau,

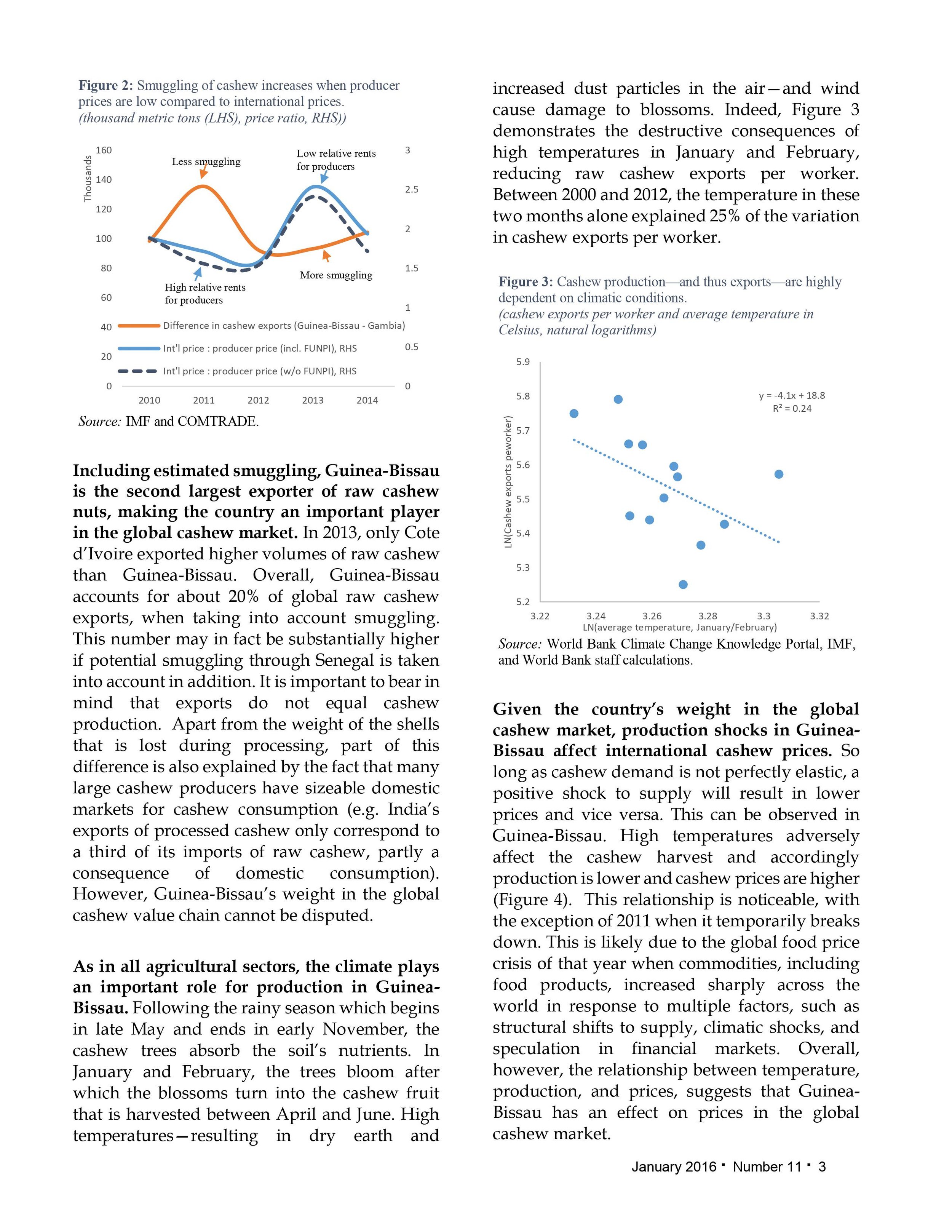

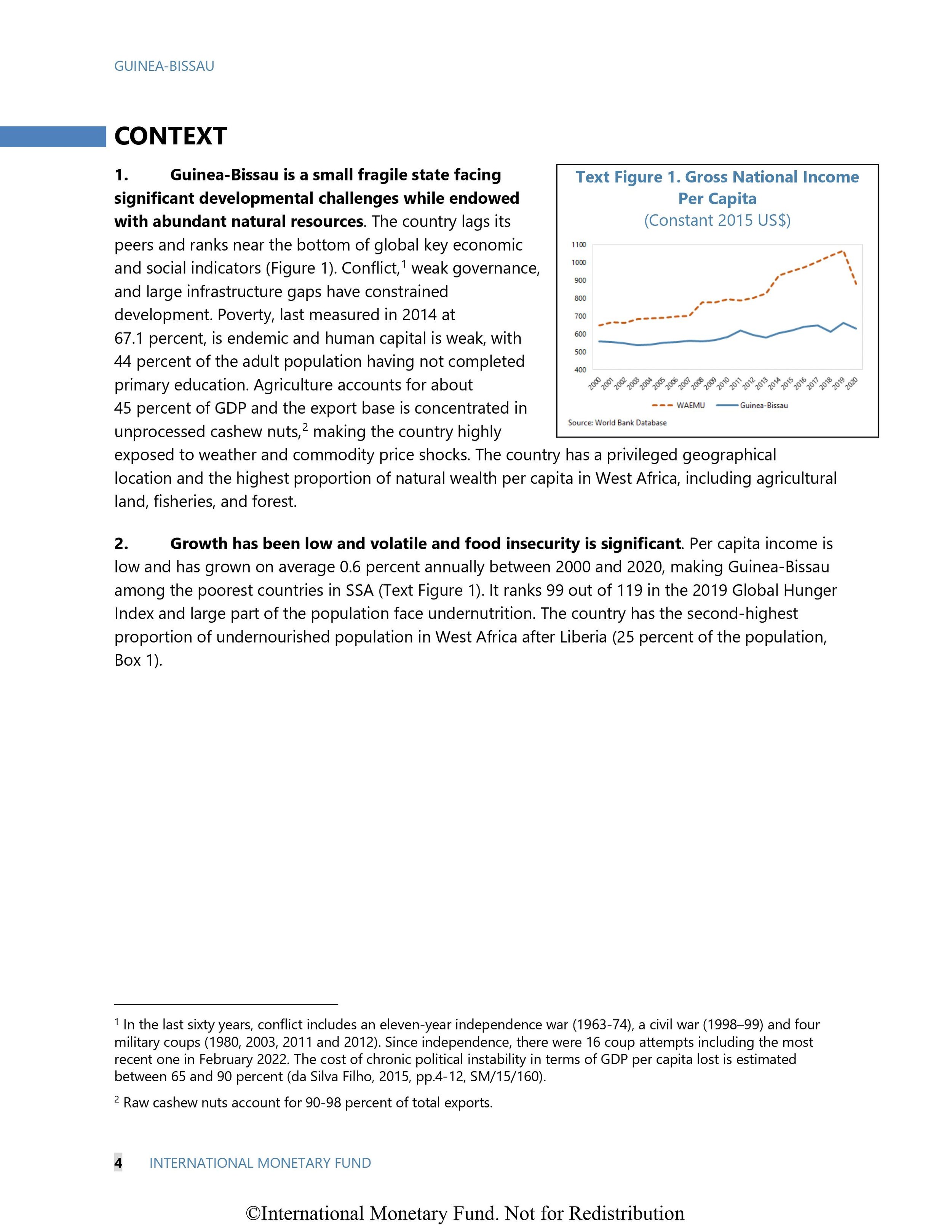

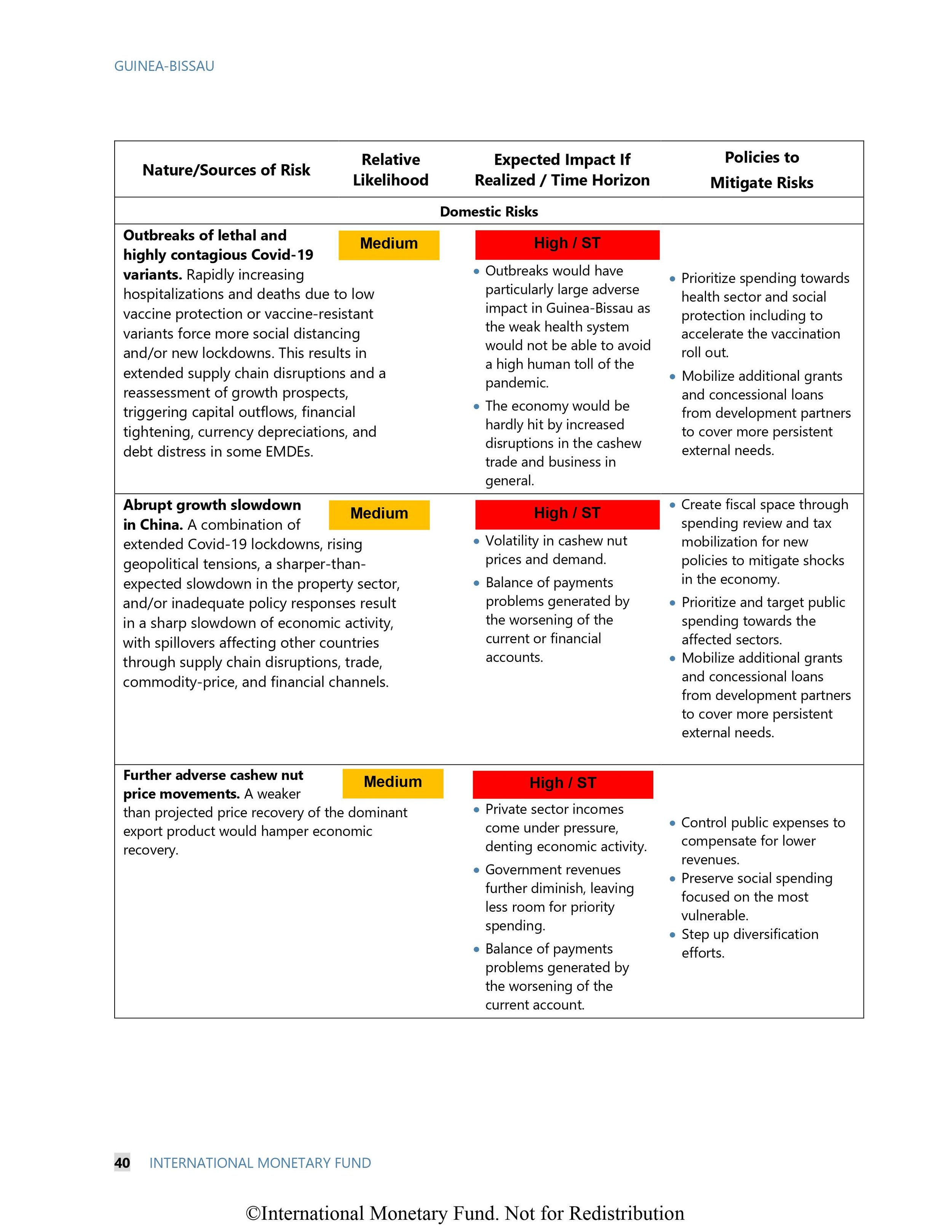

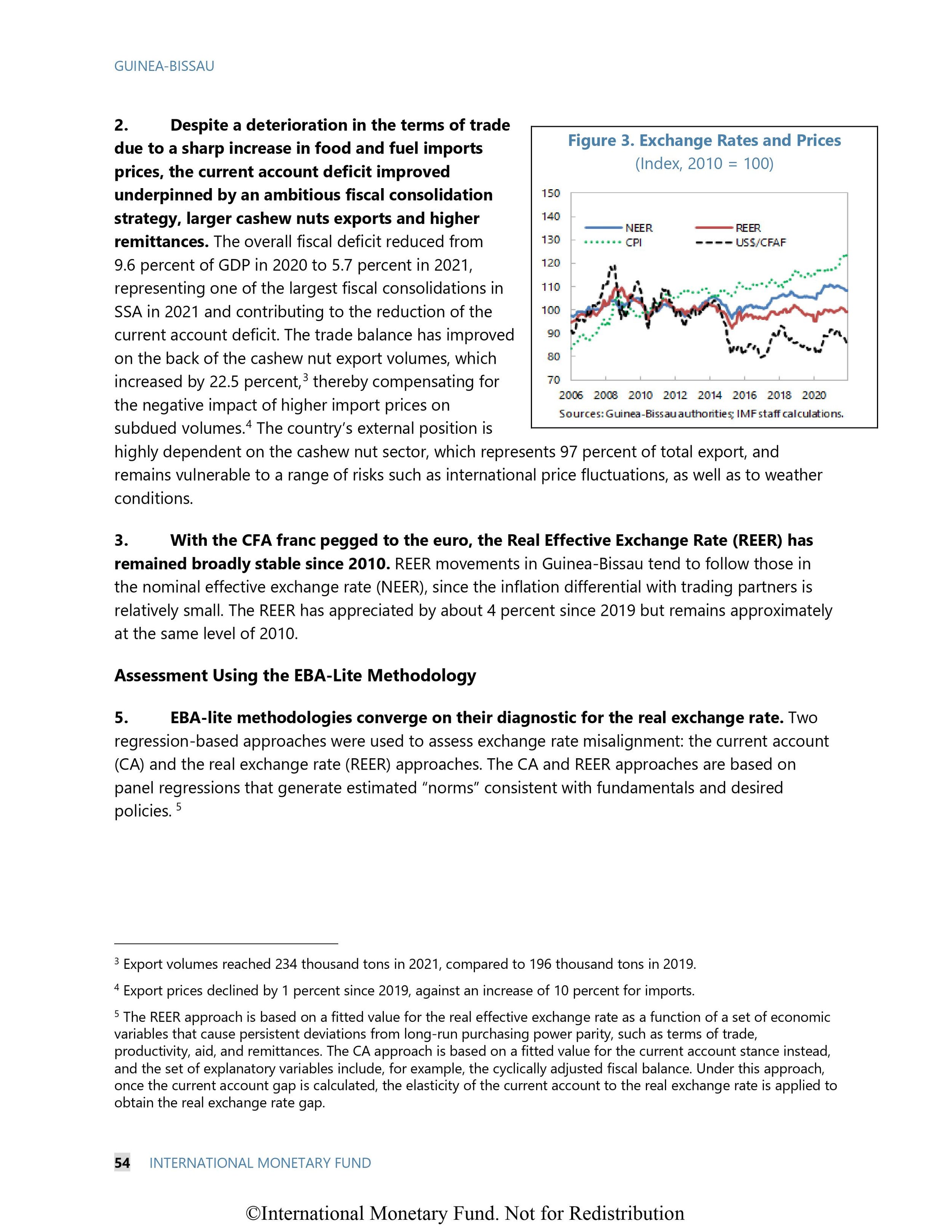

“From a macroeconomic perspective, Guinea Bissau faces two major challenges: low productivity and high vulnerability. Apart from a history of fragility which has been underlying Guinea-Bissau’s stop-and-go character of development, structural economic challenges keep the country from growing at a faster pace that would enable progress toward reducing the high levels of poverty. The dominant cashew sector at least partly lies at the heart of the structural challenges. Whilst export volumes have increased, deteriorating Terms of Trade—especially with respect to rice for which cashew is bartered—have been undermining incomes, domestic savings, and in turn investment. This at least partly explains low productivity levels and the structural slack in the economy. It leaves the country dependent on international aid which is volatile and aggravates the effect of military coups through plummeting public investment—especially given the low levels of domestic revenue. Both Terms of Trade shocks and political shocks are thus amongst the most important sources of vulnerability for Guinea-Bissau’s economy.

Investments to make the cashew sector more productive, but especially to diversify the economy, will be crucial for Guinea-Bissau. The country requires both more jobs and more productive jobs. This is especially true given expected pressures on the labor market from demographic change. Whilst there is room to improve the productivity of the cashew sector, for example by moving into processing rather than raw exports (see 2015 CEM), many of these new jobs will have to be located in other activities. The 2015 CEM and the latest national development plan identify rice, fisheries, tourism, and even mining as potential areas to add productive jobs. The production of groundnuts or sesame are other alternatives. Switching into these areas can not only raise productivity but also diversify the economy, reducing its vulnerability to the cashew price. Attracting FDI by improving the business climate can reduce the country’s dependence on donors for investment and generate knowledge spillovers that can help with the country’s economic transformation.”

A 2015 report stated,

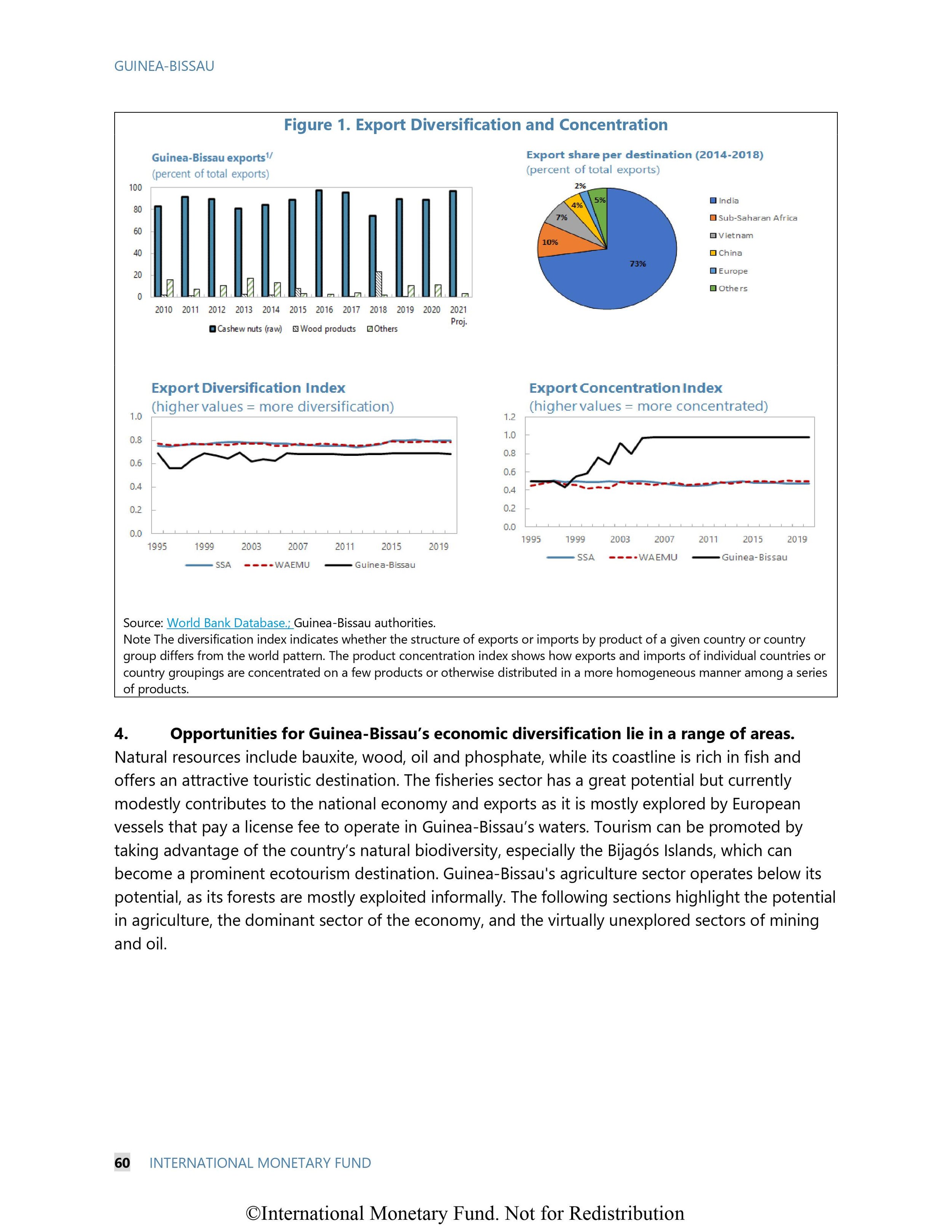

“According to the Minister of Economy and Finance, ‘The cashew campaign is the main source of income of our farmers and the main export commodity of Guinea-Bissau, and about 90 percent of our exports are cashew nuts, a tremendous weighting in our GDP.’

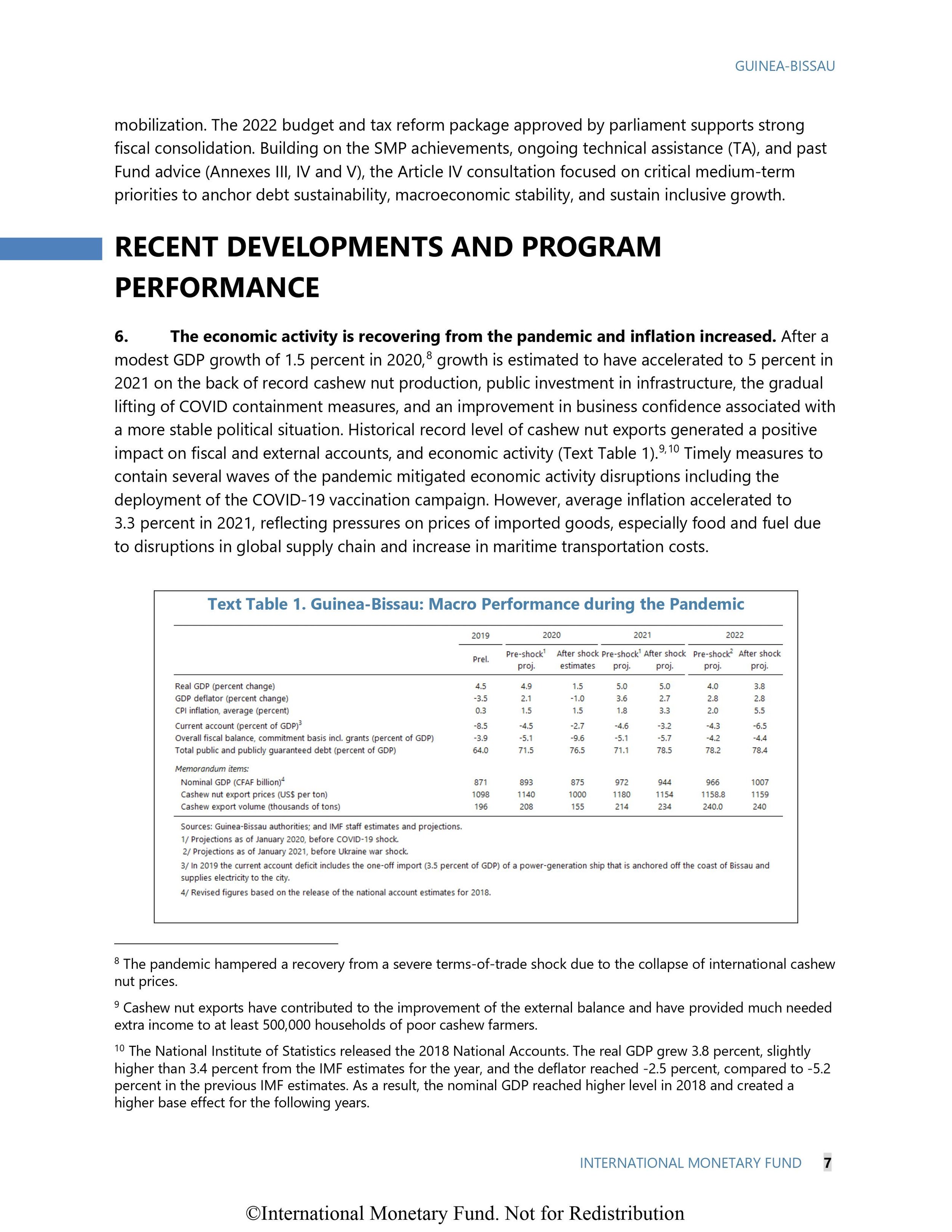

‘In 2015 about 175,000 tons of cashew were exported and this year, we expect to export 180 000 tons, probably a little more given the good prospects for this year's campaign,’ Geraldo Martins explained.

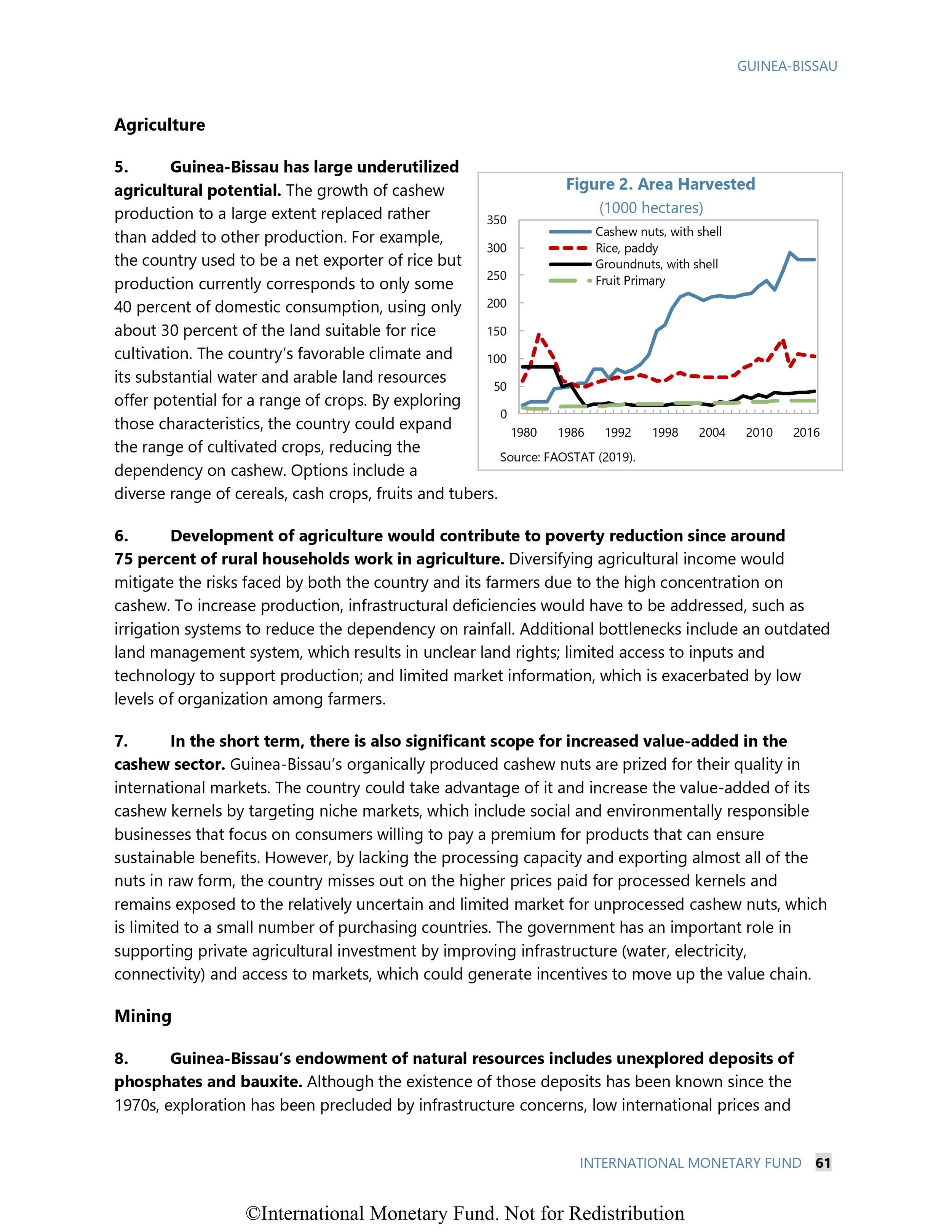

Due to the importance of cashew to the national economy the government in its development strategy focuses on the work of its entire chain, since its production, marketing to export.

‘If all the annual production was transformed locally before export of the finished product, certainly the gain would be much more important, because it would bring added value to the product, given that the price charged for a kilo of raw nuts would not be the same’" he added.

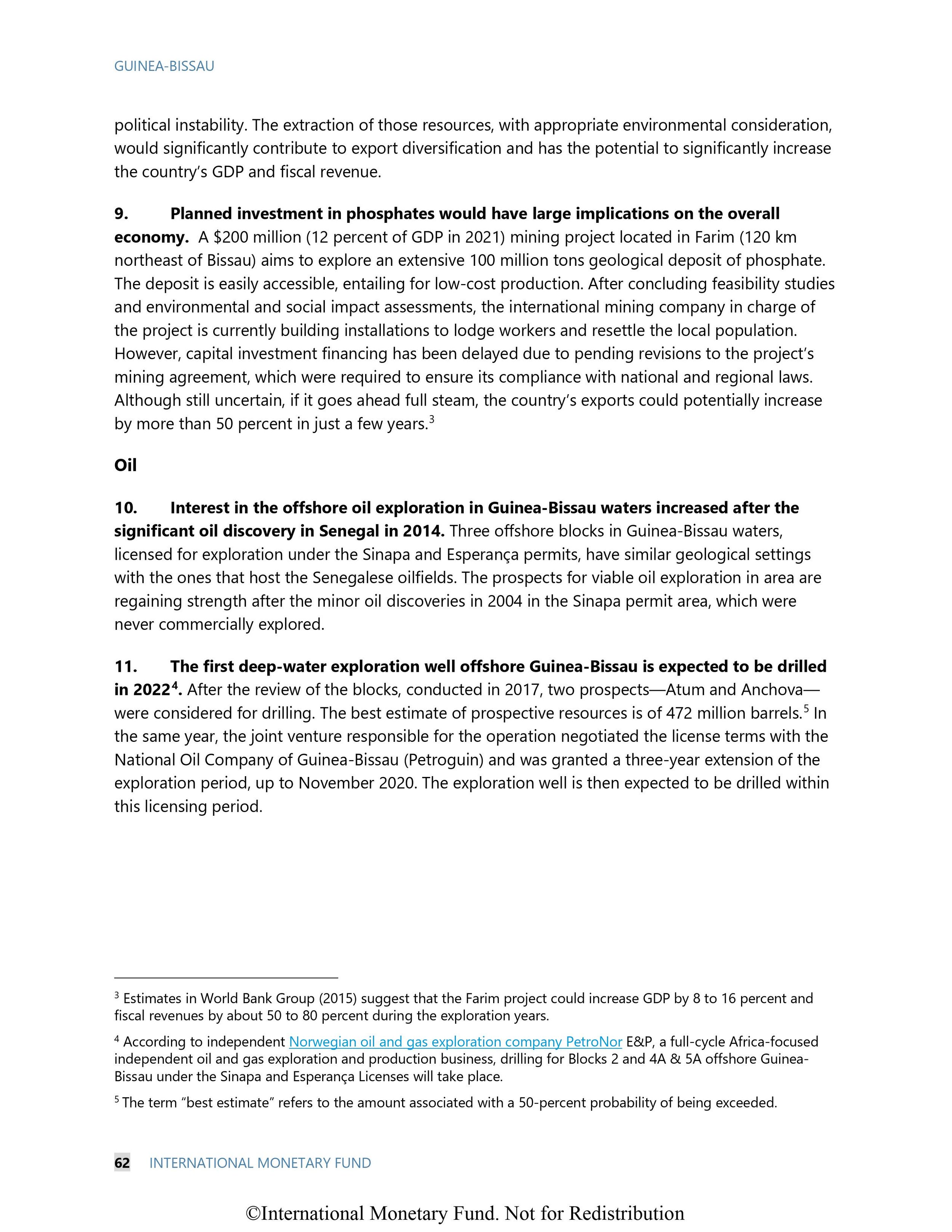

The main obstacles to the transformation of cashew are the acquisition of raw materials for processing, and the actual price of the raw material, said Josué Gomes de Almeida, Coordinator of the Rehabilitation of Private Sector and Support to Agro-industrial Development Project, funded by the World Bank.

‘When the market is good in terms of the price paid to producers, all transformers cry, and when the price is bad for producers, everyone talks about local transformation,’ said Jose Gomes de Almeida, stressing the need for this contradiction to be resolved since ‘in government policy, the fight against poverty must be reflected in rural world where cashew is produced.’

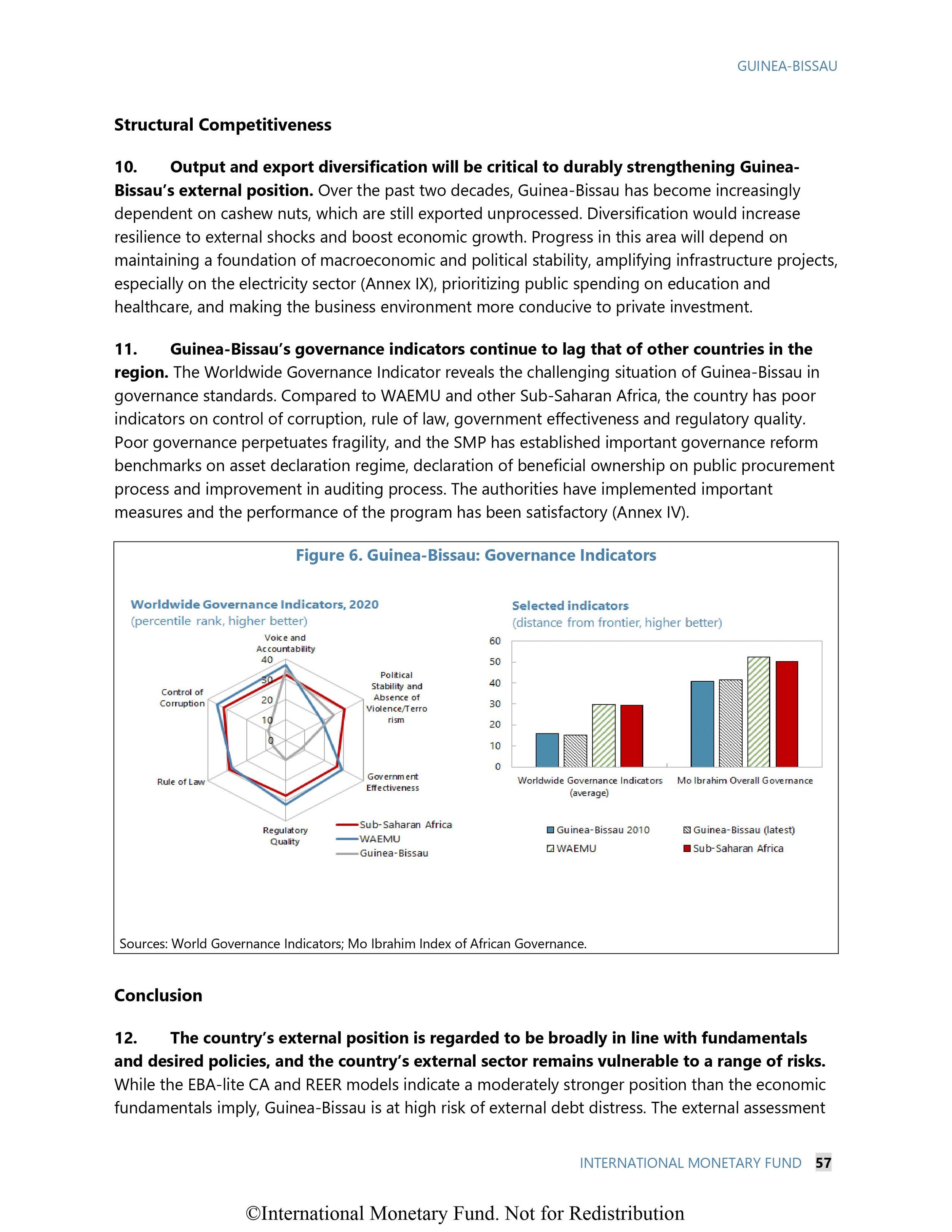

Rui Fonseca, Assistant FAO Programs, recalled that the diversification of agricultural production in the country ‘is important’ and that why his agency will launch ‘a program in partnership with the European Union at the end of April, for cashew improved production quality and also for the development of horticulture.’”

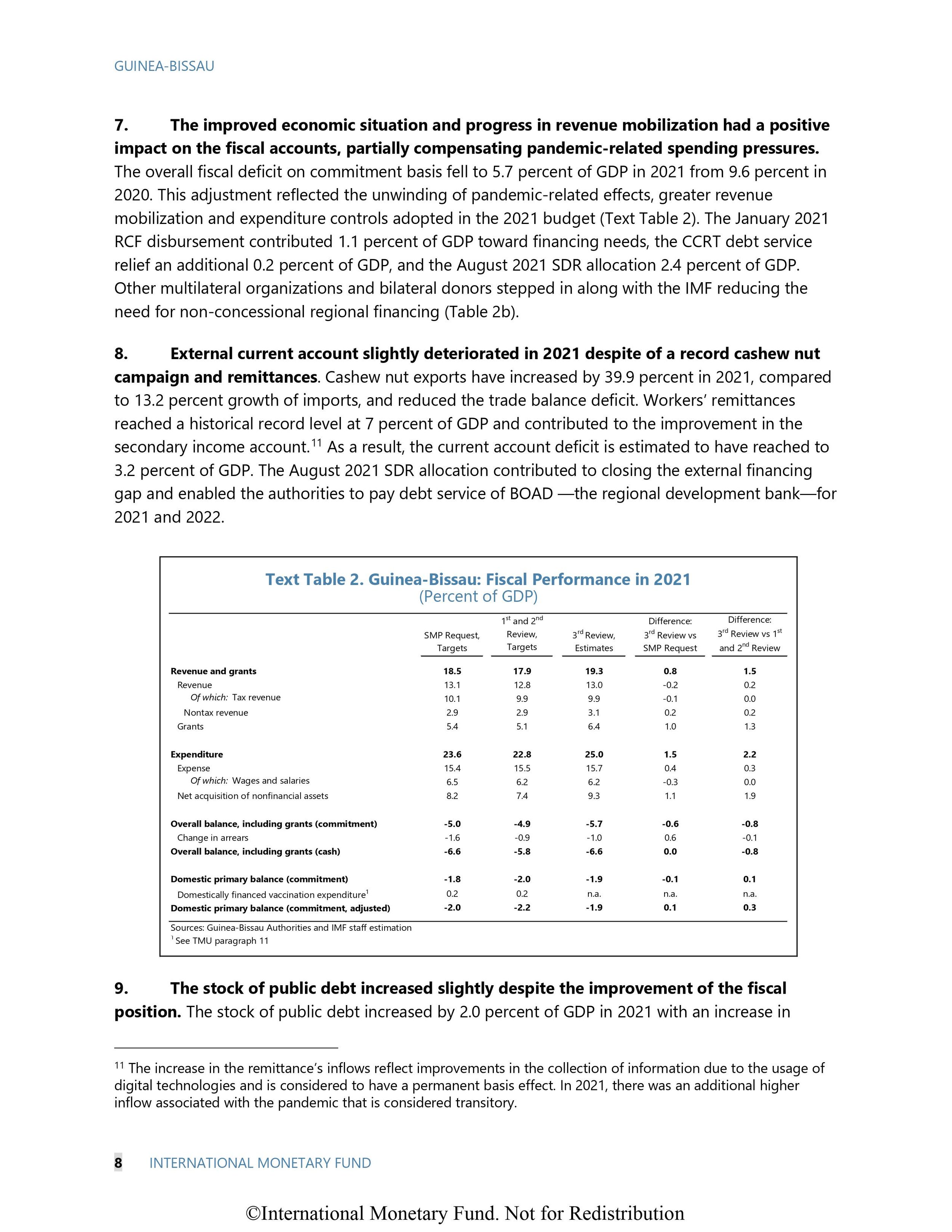

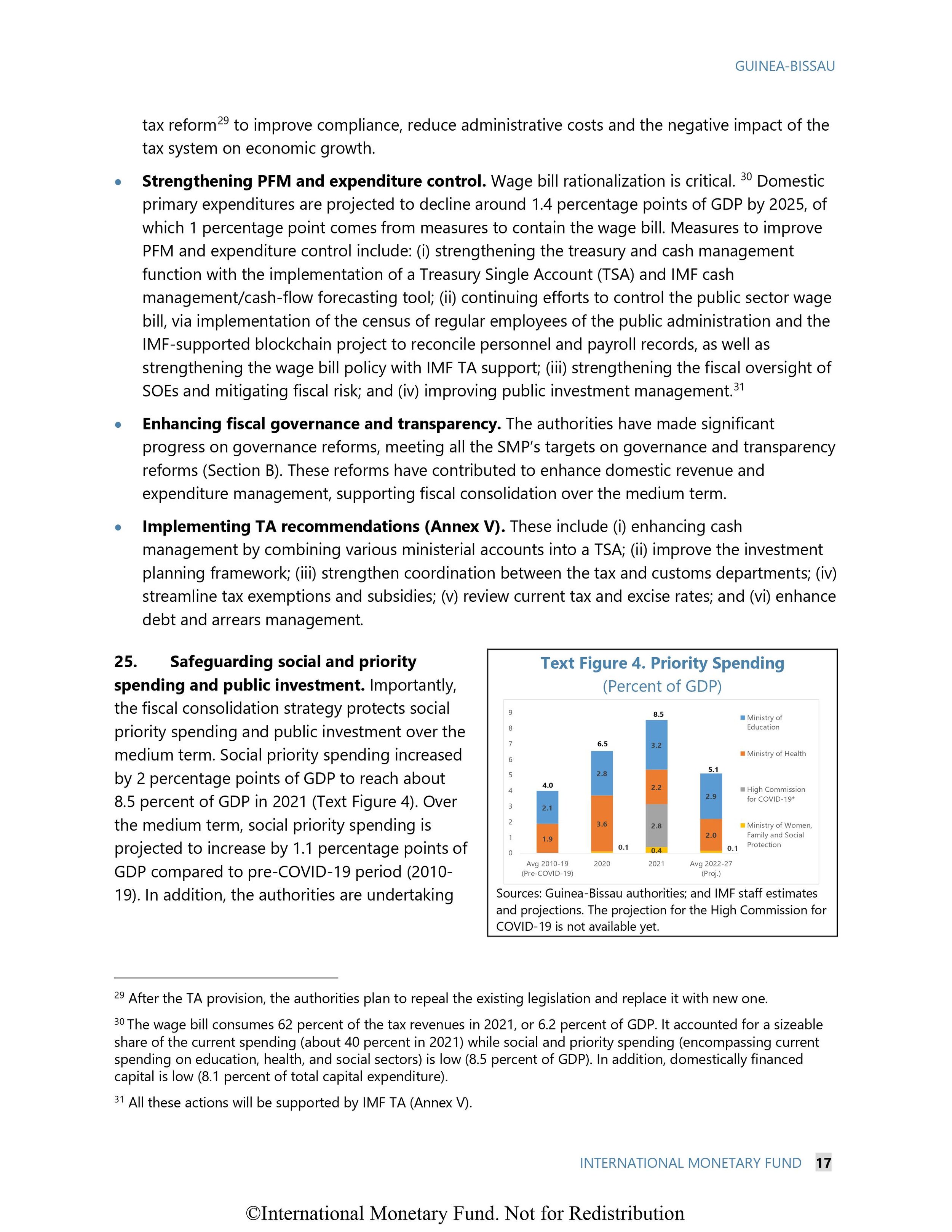

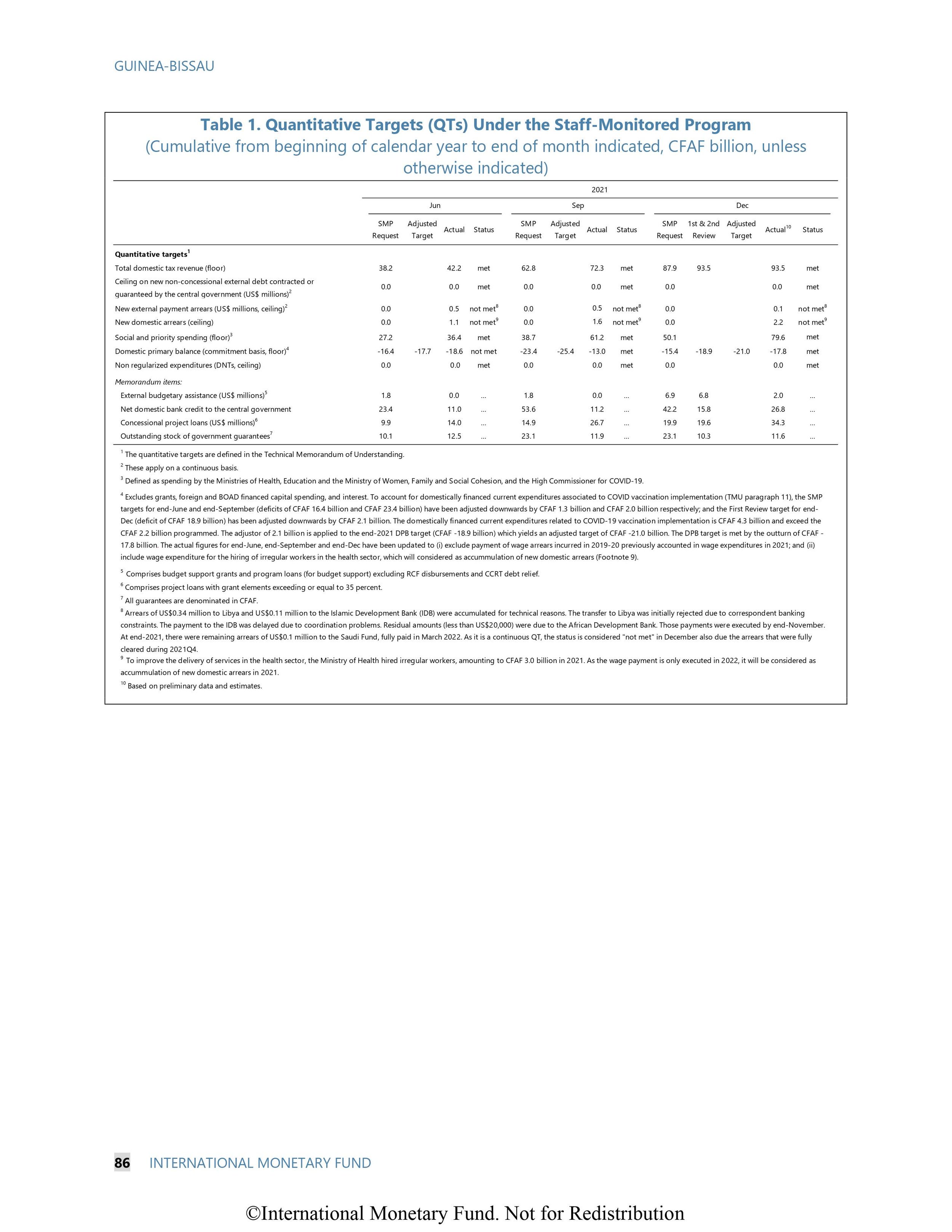

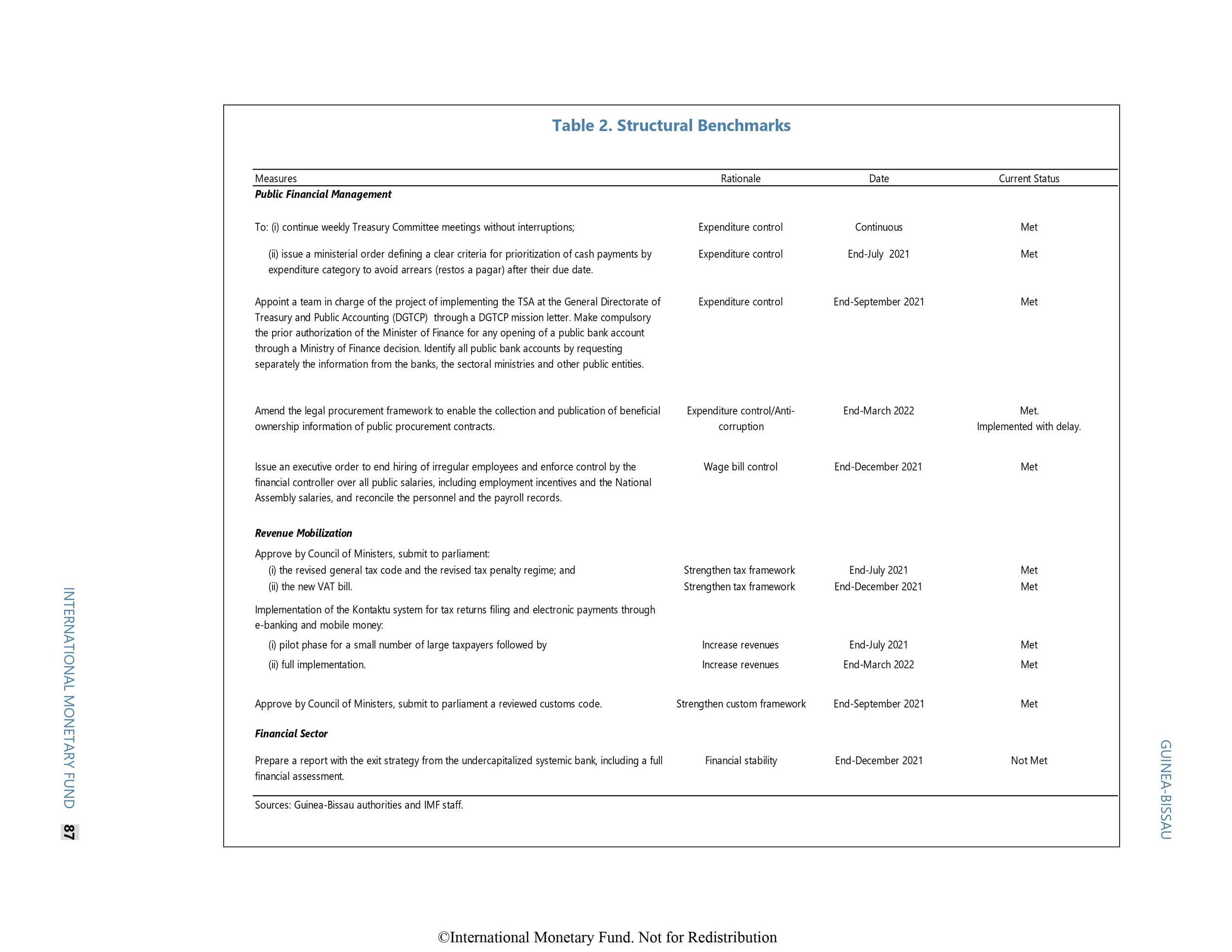

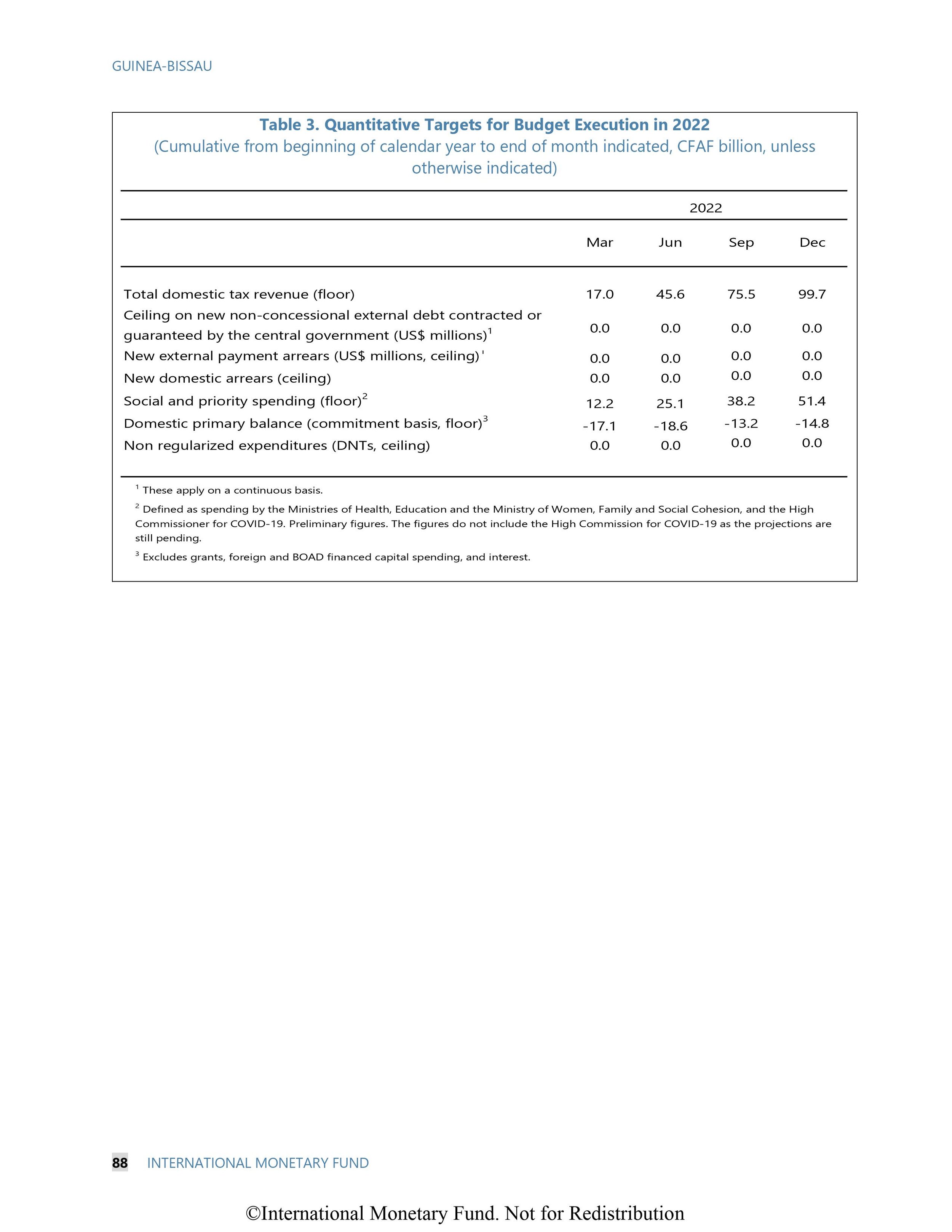

Now consider that Guinea-Bissau: 2022 Article IV Consultation and Third Review under the Staff-Monitored Program highlighted that,

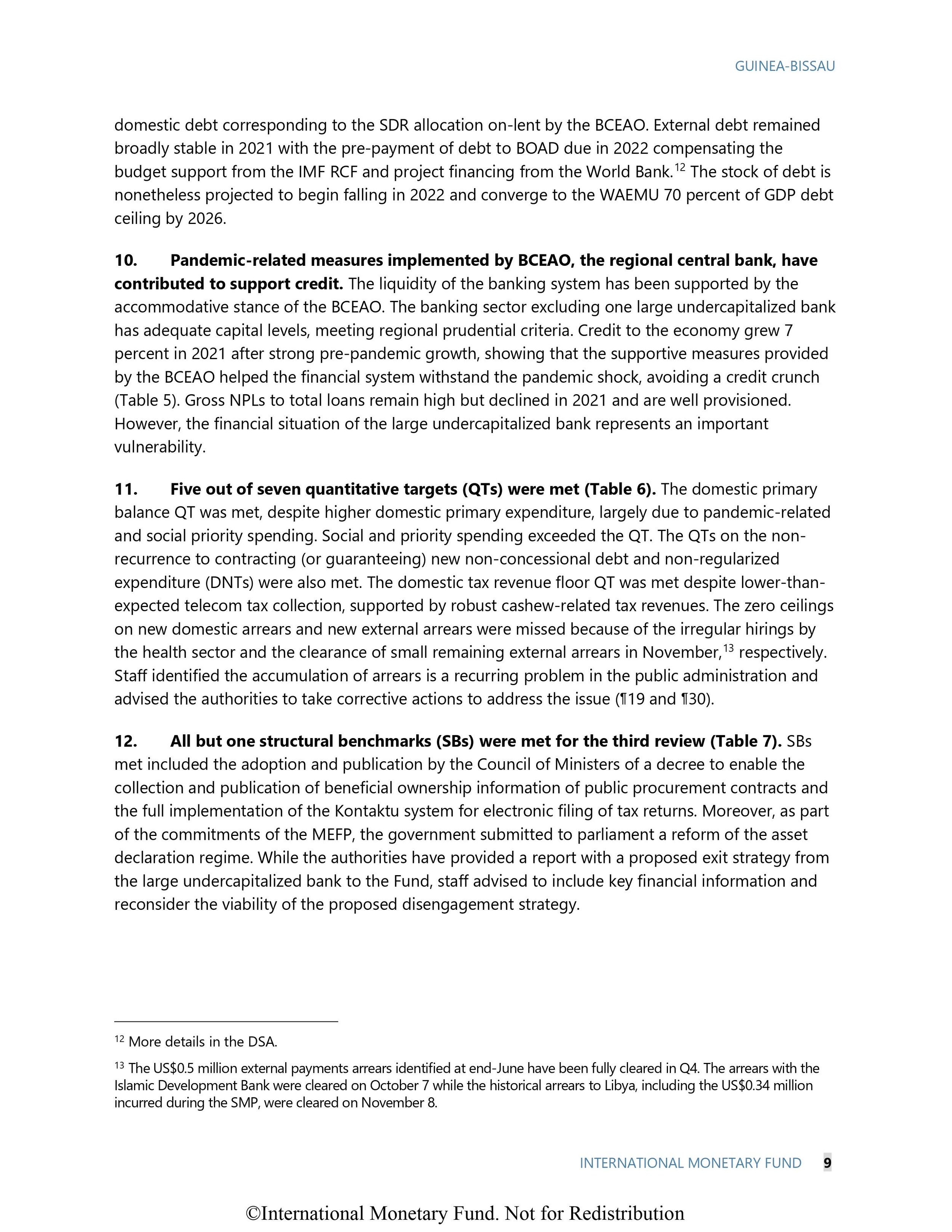

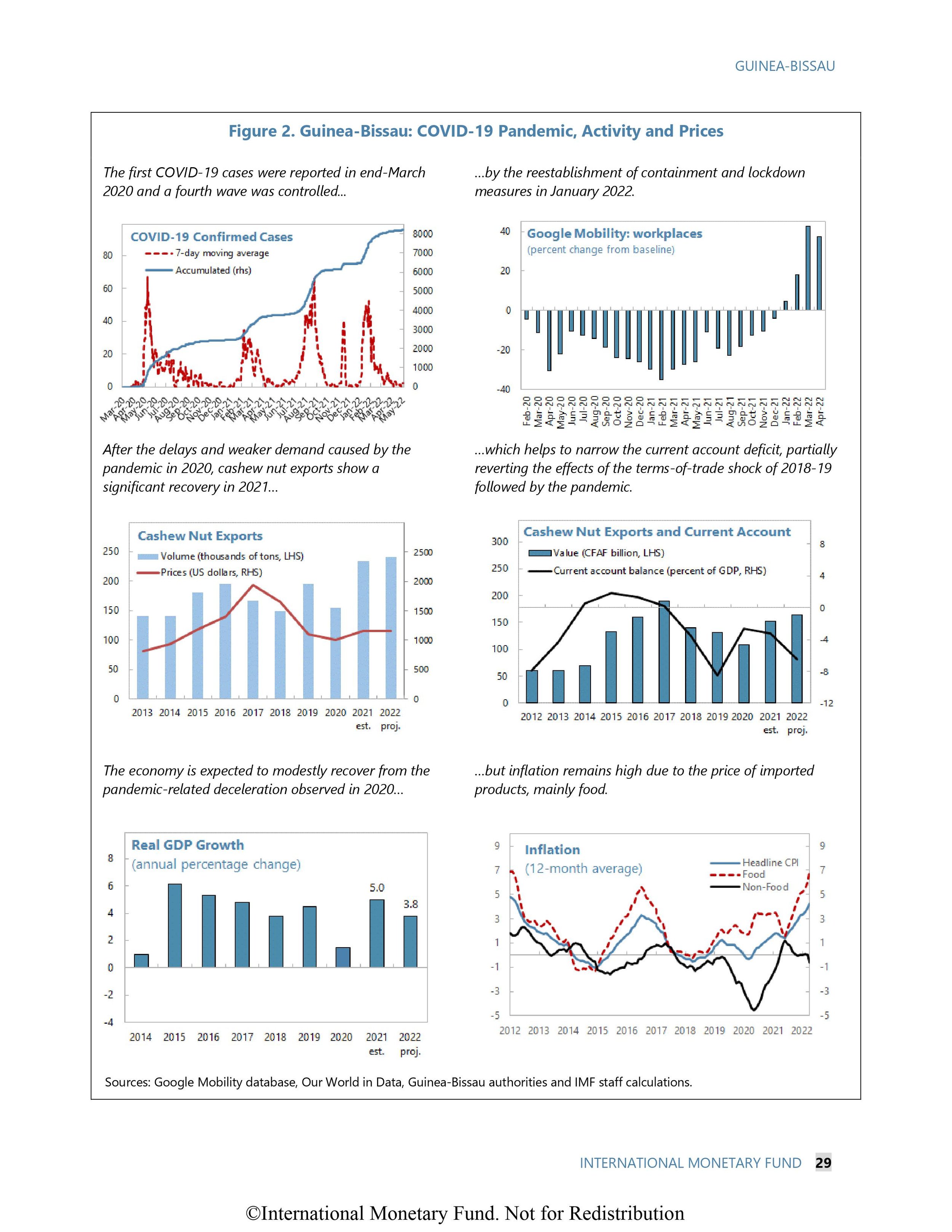

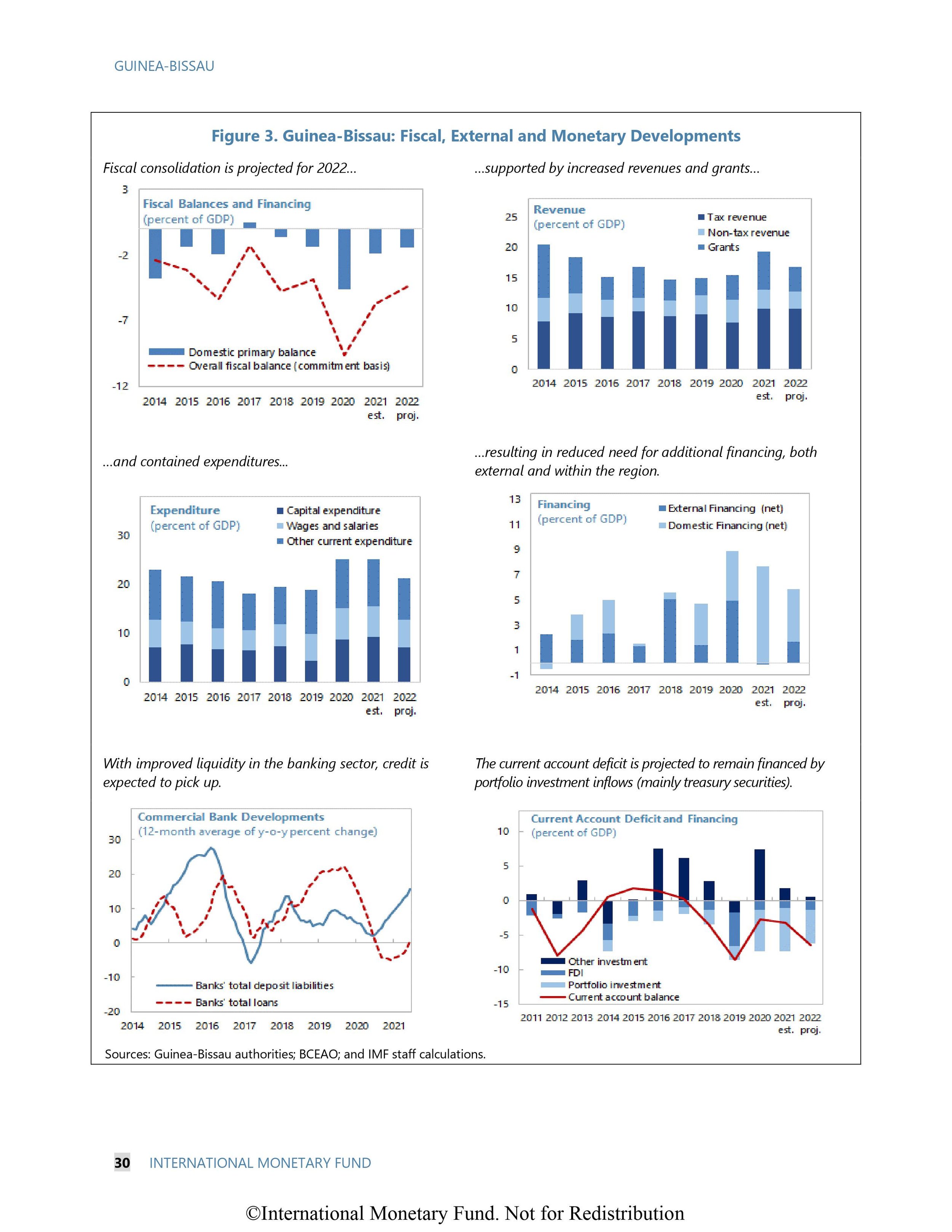

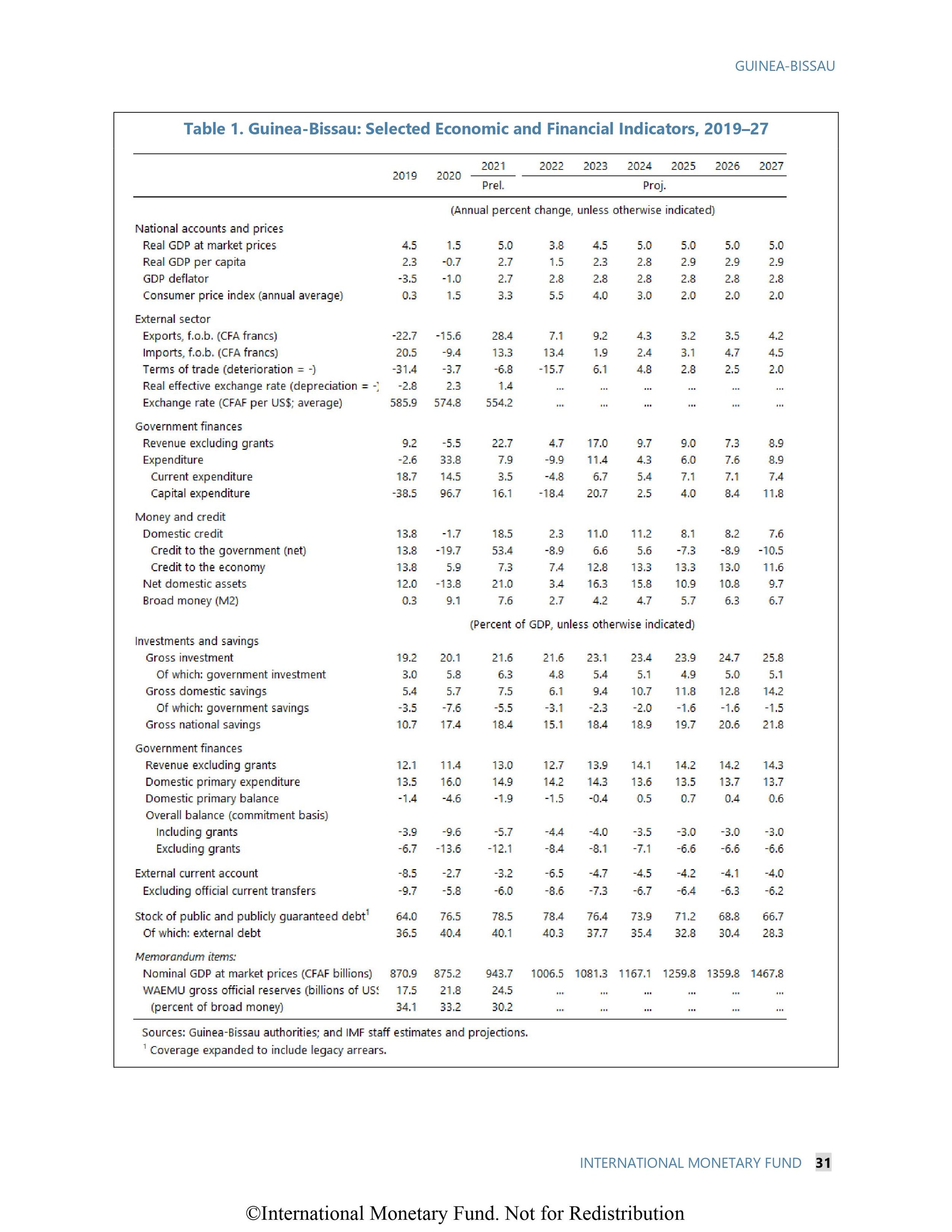

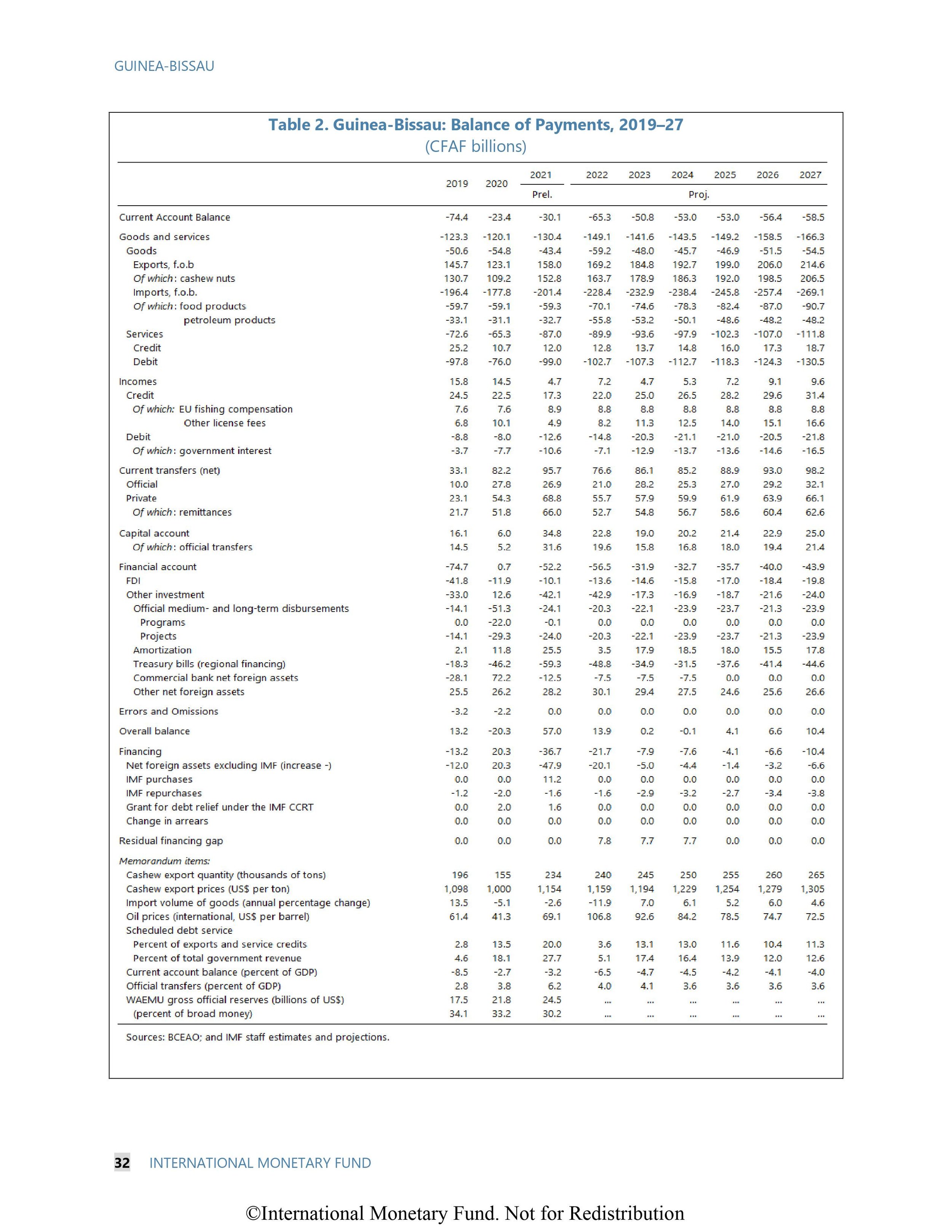

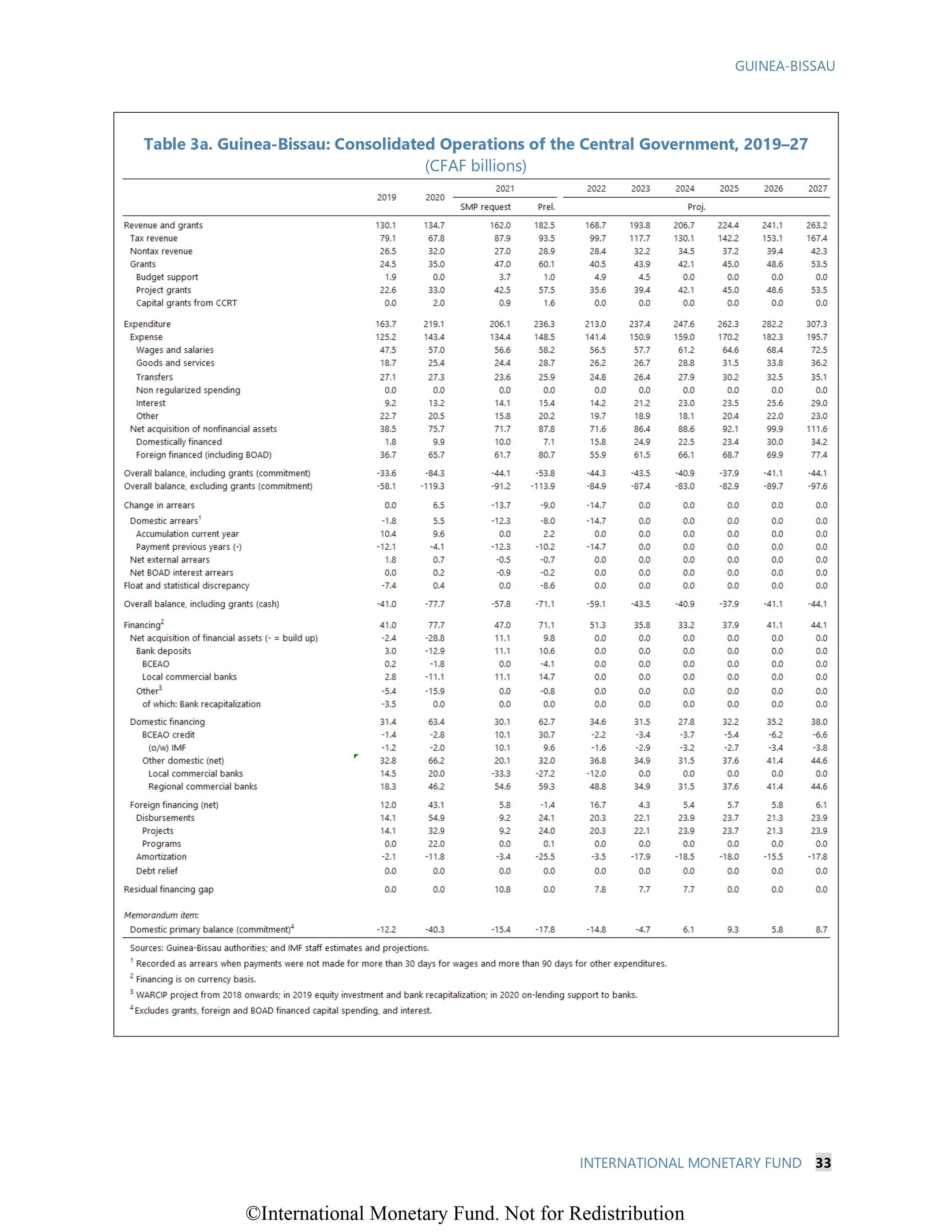

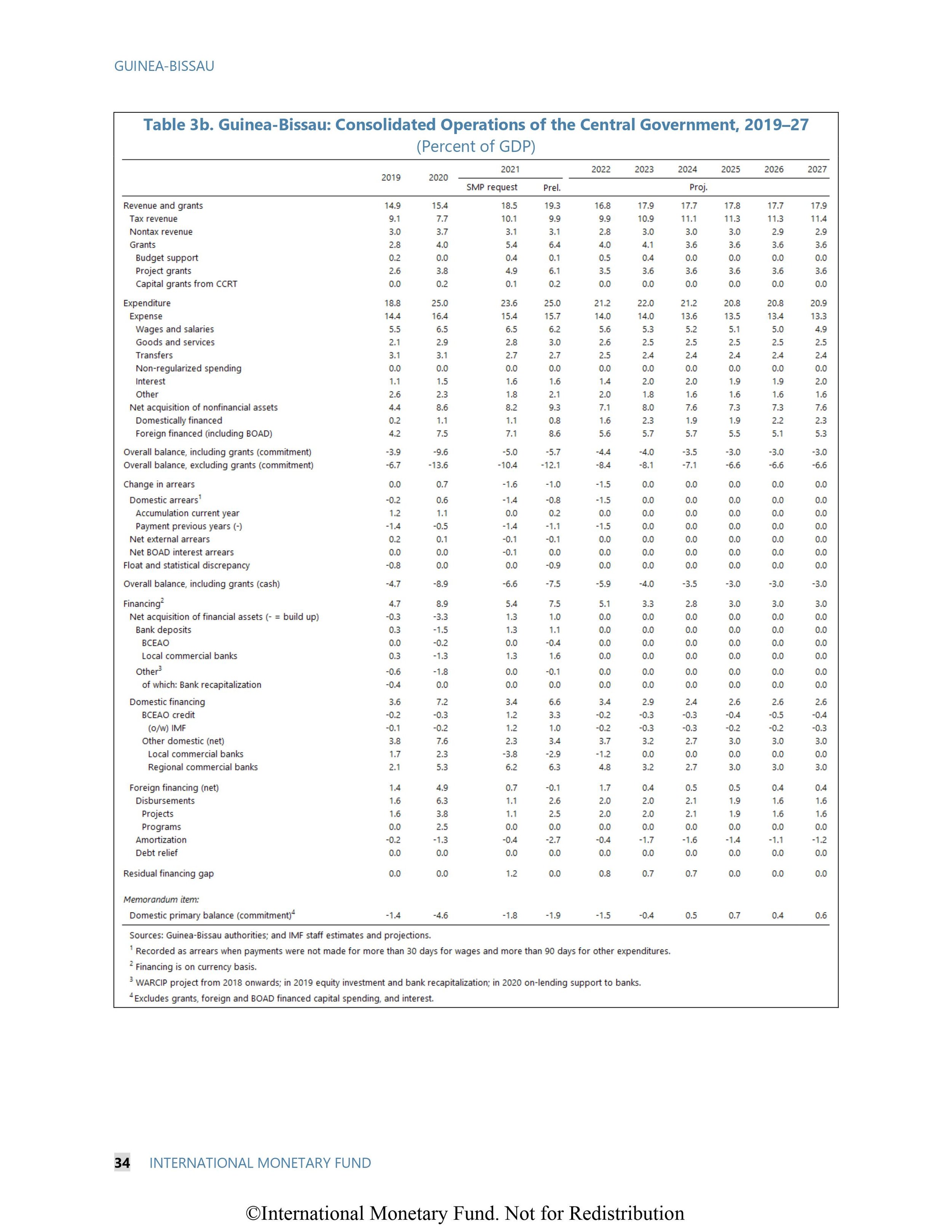

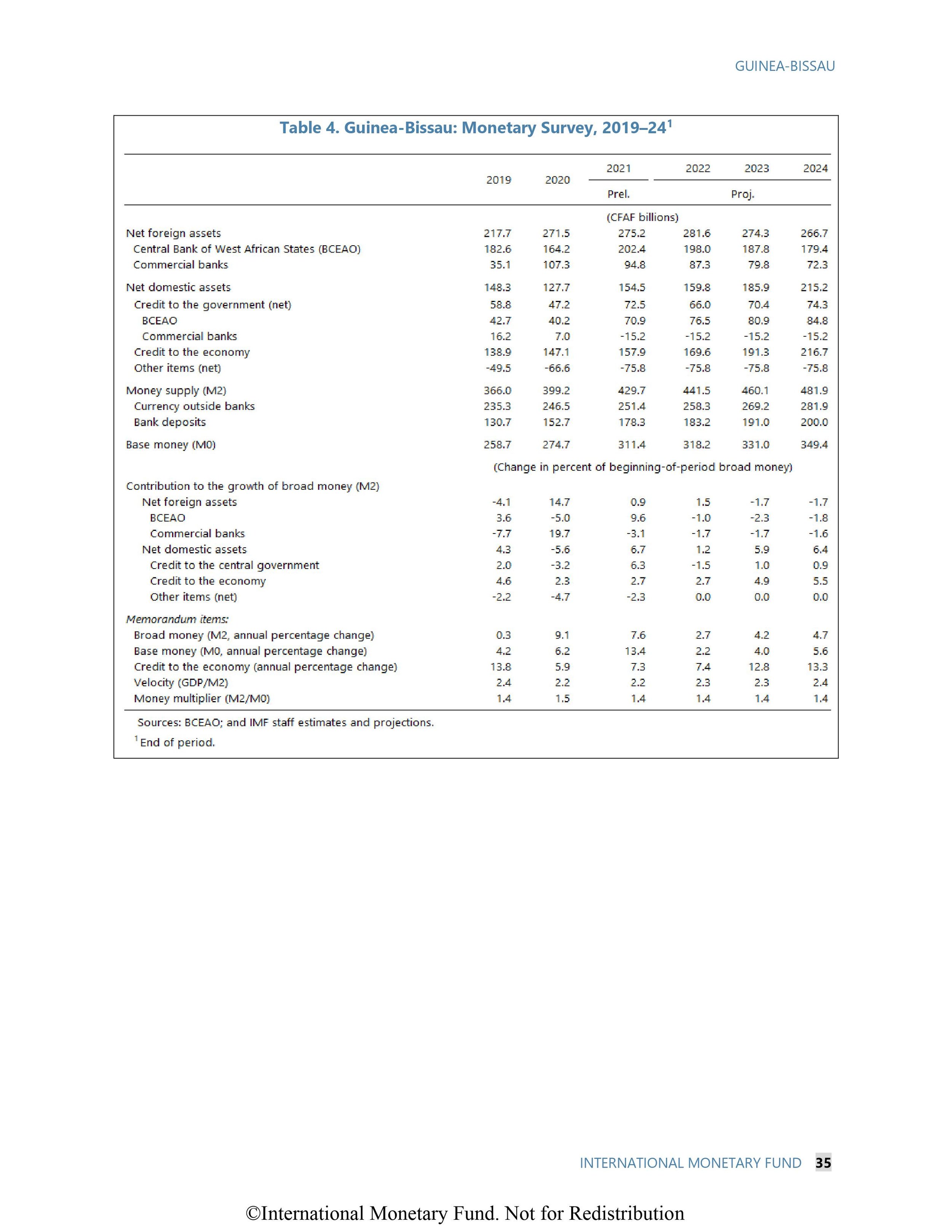

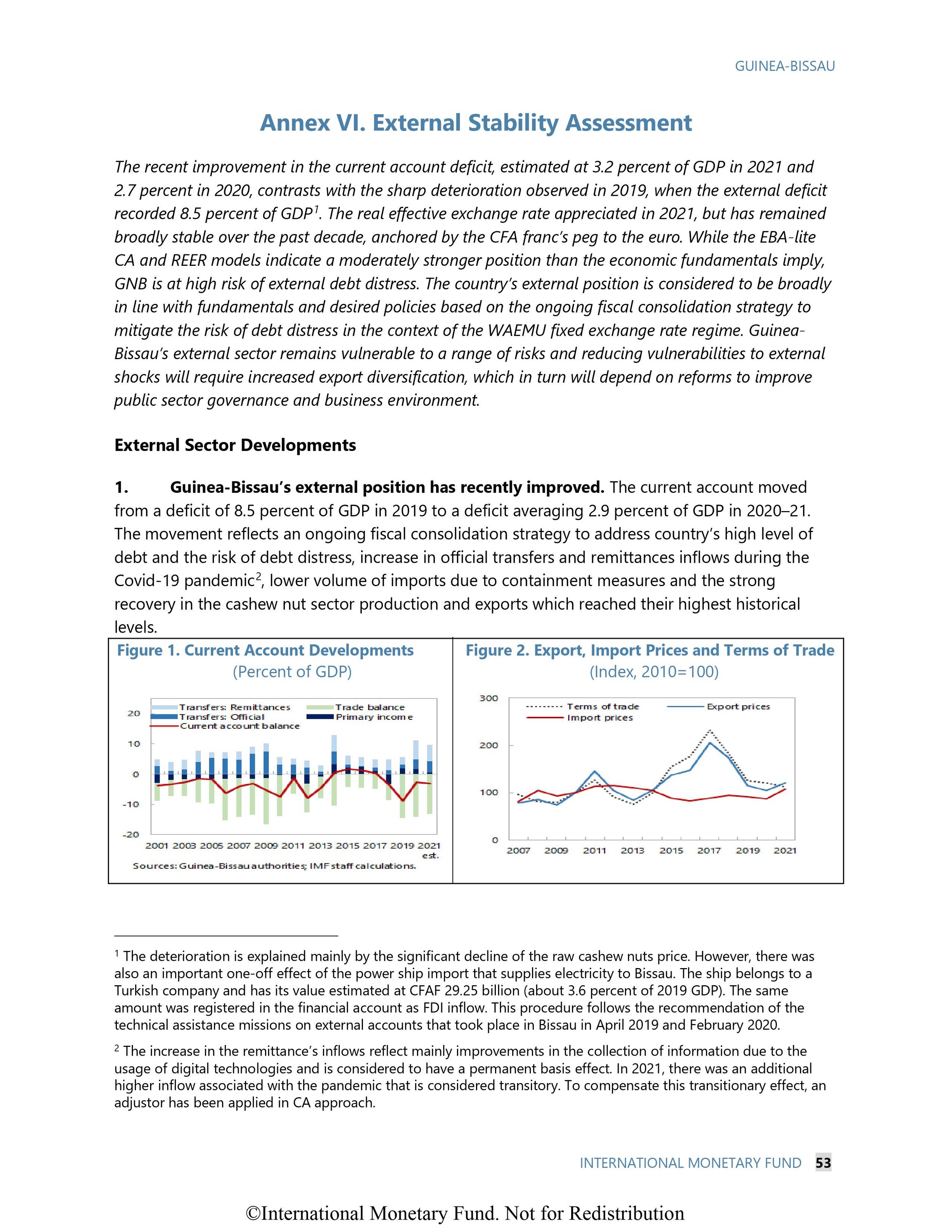

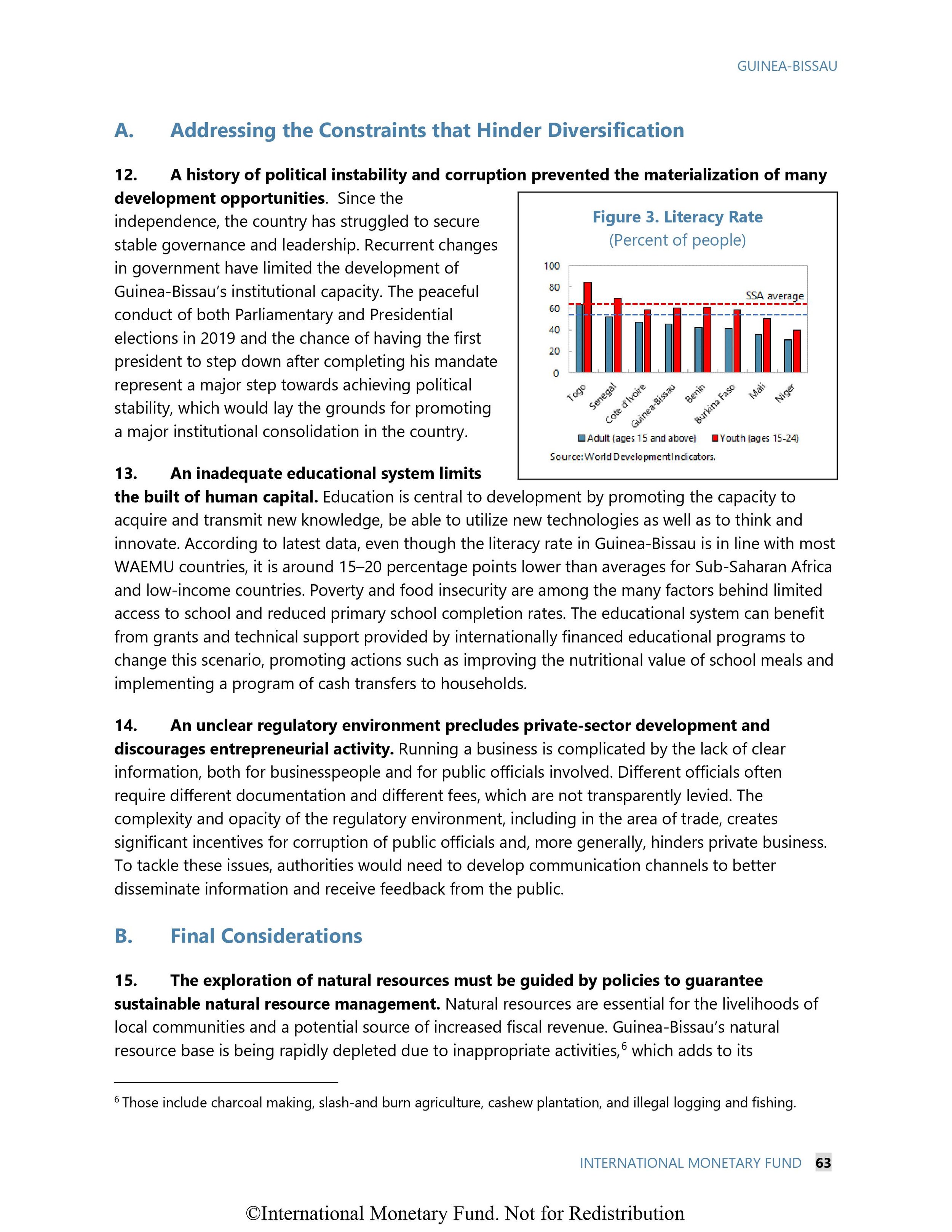

“External current account slightly deteriorated in 2021 despite of a record cashew nut campaign and remittances. Cashew nut exports have increased by 39.9 percent in 2021, compared to 13.2 percent growth of imports, and reduced the trade balance deficit. Workers' remittances reached a historical record level at 7 percent of GDP and contributed to the improvement in the secondary income account. As a result, the current account deficit is estimated to have reached to 3.2 percent of GDP. The August 2021 SDR allocation contributed to closing the external financing gap and enabled the authorities to pay debt service of BOAD —the regional development bank—for 2021 and 2022.

9. The stock of public debt increased slightly despite the improvement of the fiscal position. The stock of public debt increased by 2.0 percent of GDP in 2021 with an increase in domestic debt corresponding to the SDR allocation on-lent by the BCEAO. . . .

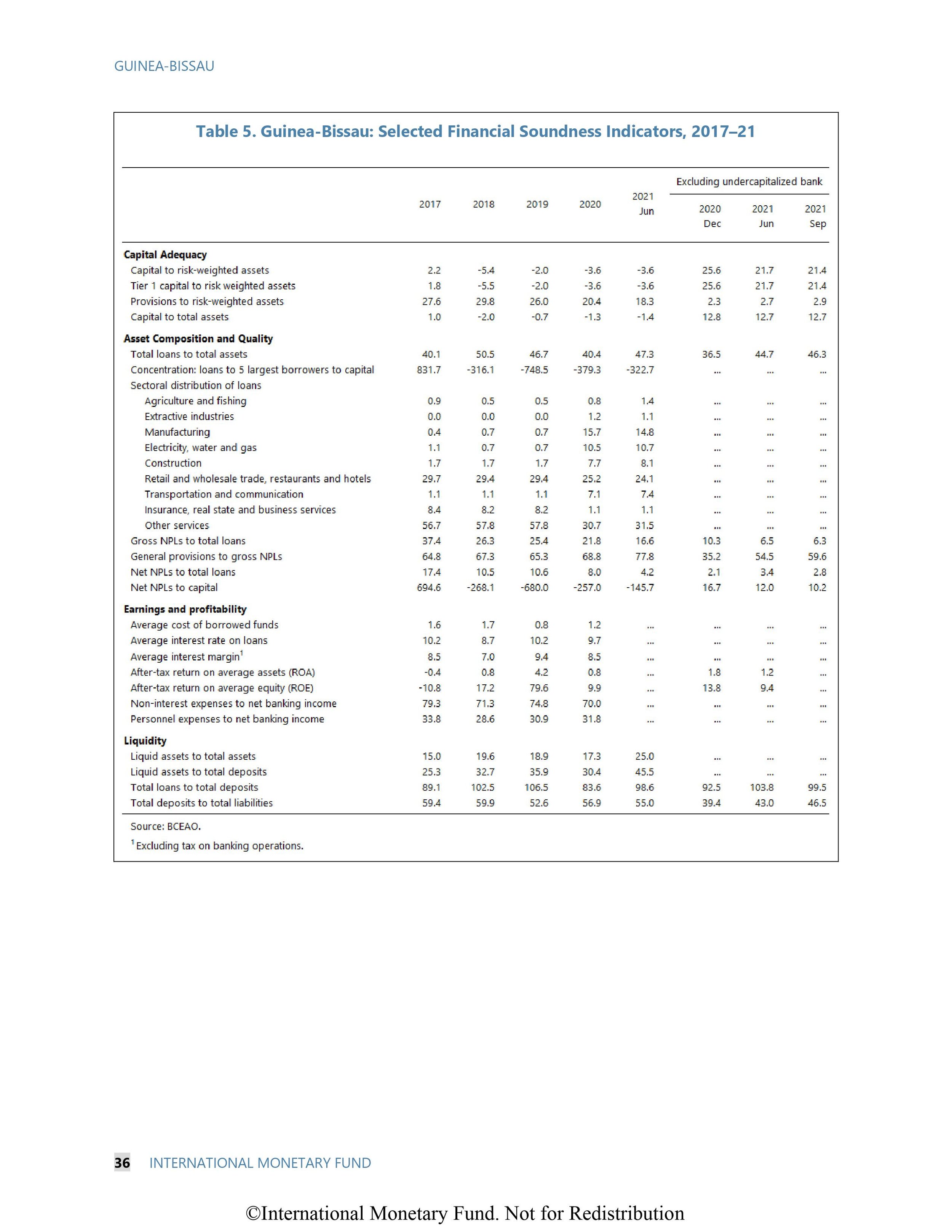

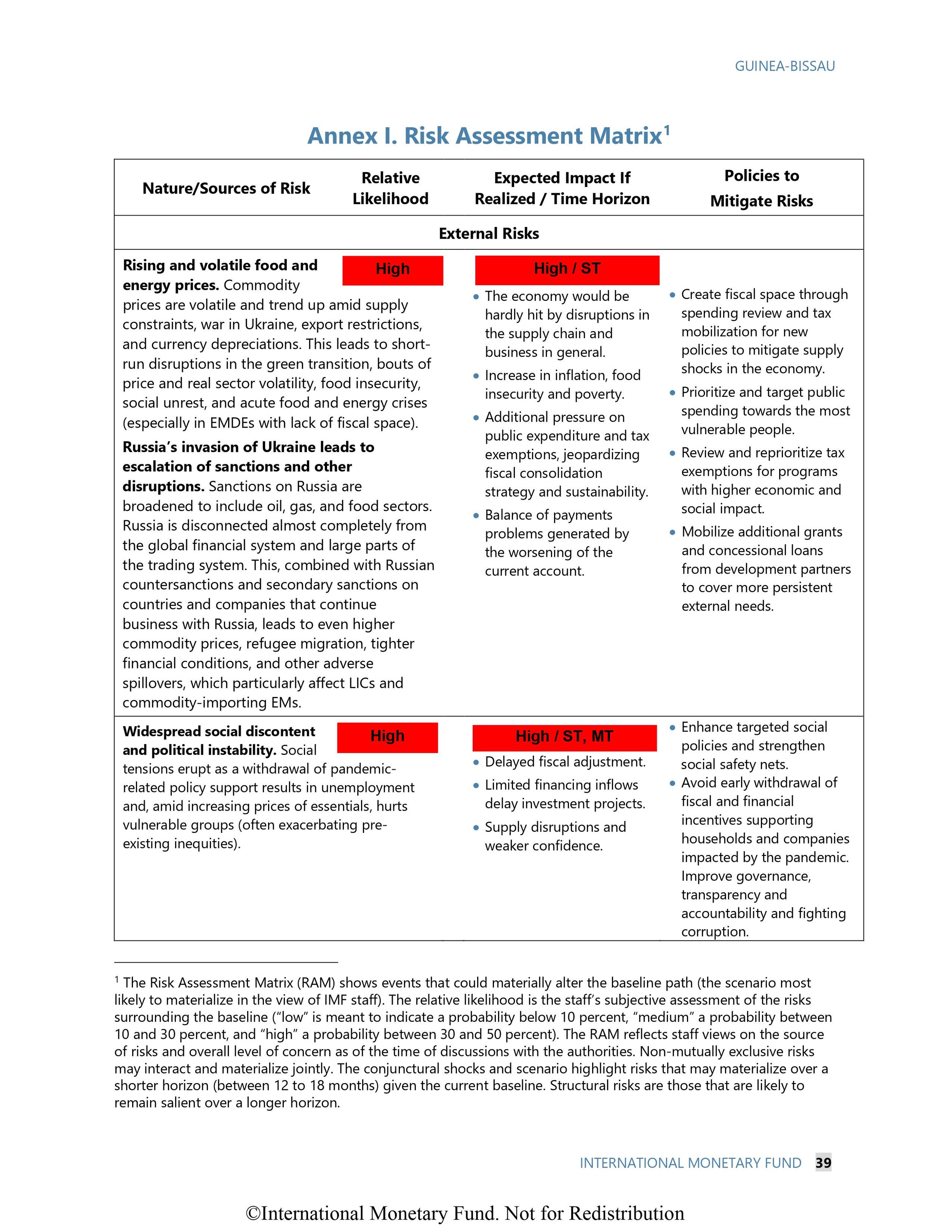

32. Guinea-Bissau is at a high risk of external and overall debt distress. With the reclassification of BOAD, the share of external debt reaches 40.1 percent of GDP (from 26.7 percent in the July 2021 DSA). The risk of external debt distress is high because the indicators based on the debt-service ratios breach their indicative thresholds under the baseline. Overall risk of debt distress is also high because the PV of public debt relative to GDP remains well above its indicative benchmark throughout the projection period (DSA). . . .

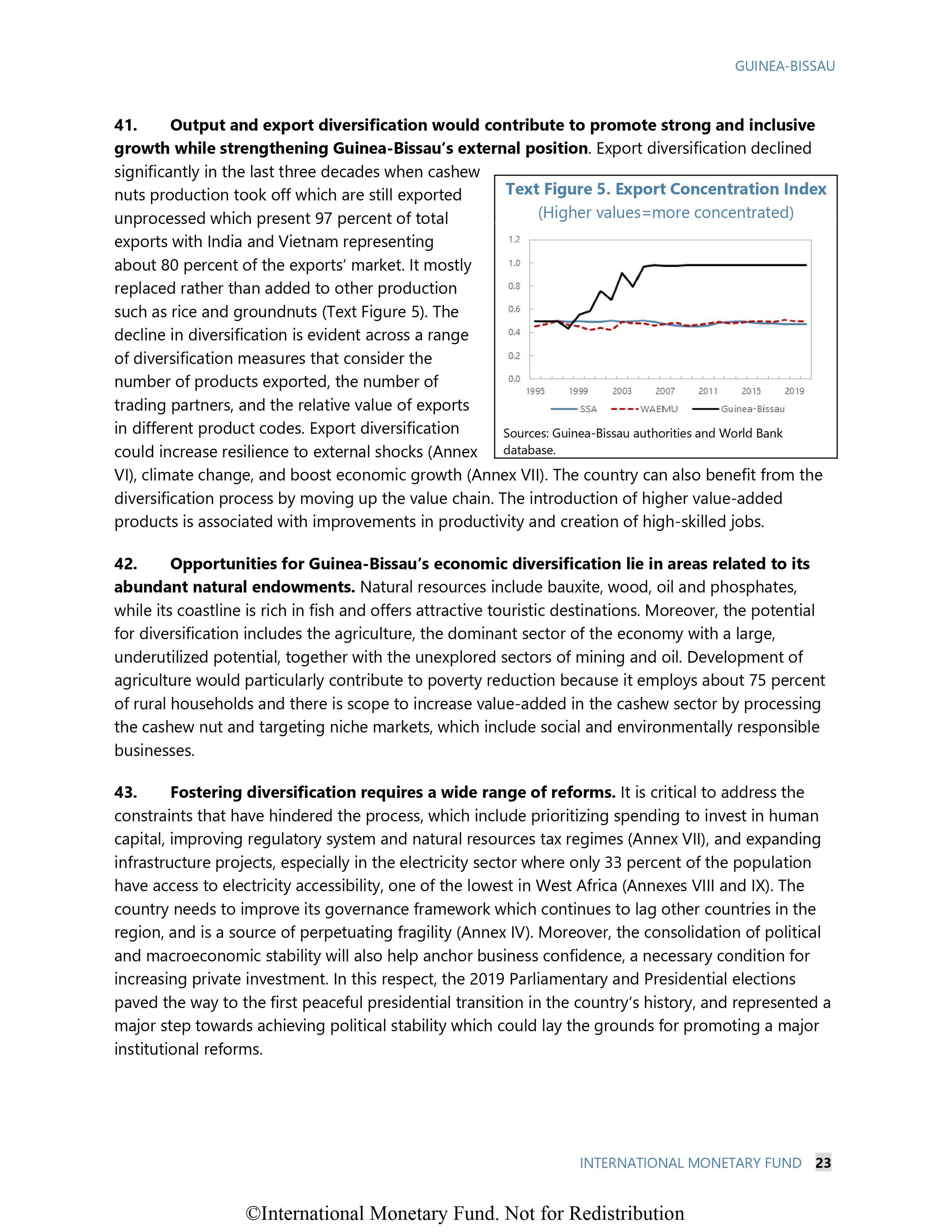

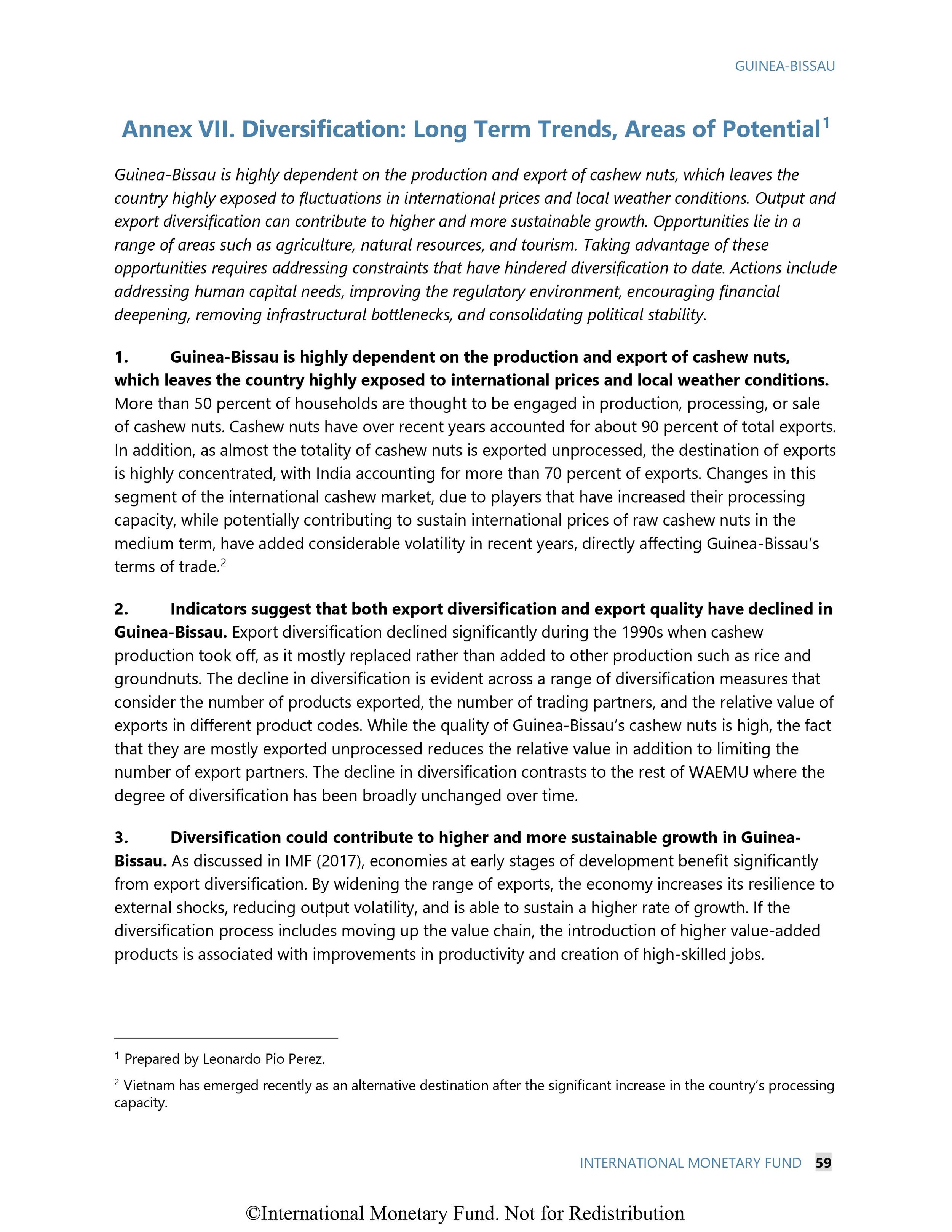

41. Output and export diversification would contribute to promote strong and inclusive growth while strengthening Guinea-Bissau's external position. Export diversification declined significantly in the last three decades when cashew nuts production took off which are still exported unprocessed which present 97 percent of total exports with India and Vietnam representing about 80 percent of the exports' market. It mostly replaced rather than added to other production such as rice and groundnuts. The decline in diversification is evident across a range of diversification measures that consider the number of products exported, the number of trading partners, and the relative value of exports in different product codes.”

Thus, despite a record cashew nut campaign and a 39.9% increase in cashew exports, public debt increased even while profits were used to pay debt service to the regional development bank.

Meanwhile, cashew funds continue to pour in. In February of 2022, O Democrata reported that the National Cashew Agency of Guinea-Bissau made plans to boost the productivity of farms from 300 kg of cashew nuts per hectare to 1,500 kg. The newspaper quoted the head of the agency, Caustar Dafá, as saying another intention is to improve the quality of the cashew nut crop using techniques appropriate for Guinean producers. Mr Dafá said his agency had agreed in January to form a partnership enabling the transfer to Guinea-Bissau from Brazil of technology for machinery for processing cashew nuts. Alanso Fati, President of the National Association of Farmers of Guinea-Bissau, ‘Guinea-Bissau needs to invest more in technology to increase its output of cashew nuts.”

The Hindu Bussiness Line reported that

“‘Beta Group, the Kerala-based food company, which owns the Nut King brand, will be setting up an industrial unit in the West African country of Guinea-Bissau for cashew business. The company is all set to sign a $100 million MoU with the Government of Guinea-Bissau over a period of five years to procure, process, and export value-added cashew, mainly to the US and China markets,’ said J Rajmohan Pillai, Chairman, Beta Group.”

In October of 2022, China-Lusophone Brief reported,

“Chinese state-owned company Grupo Human Construção e Investimentos has agreed with the authorities of Guinea-Bissau to buy the country´s cashew nuts production and later build cashew processing units. Grupo Human signed two memoranda of understanding with the ministries of Commerce and Energy and Industry of Guinea-Bissau, after four days of market prospecting in the country. Abdu Jaquité, delegate of the Government of Guinea-Bissau to the Permanent Secretariat of Forum Macau for the Economic and Trade Cooperation between China and Portuguese-speaking countries, told RFI that initially the Chinese will buy practically the entire production of cashew nuts.

In a second phase, Hunan plans to build processing units in the country, Jaquité said at the signing of the agreements. “They want to buy, if possible, 250,000 tons, which means practically all agricultural production”, the delegate underlined, adding the Chinese plan includes “to establish a factory for processing cashew nuts right here in Guinea-Bissau”. The Chinese province of Hunan, RFI added, is available to serve as Guinea-Bissau’s gateway to the world’s largest market with around 1.5 billion consumers.”

The question must be asked, in whose interest is all this cashew investment for? Is this any different from the redemptive and extractive mono-mercantilism model that Cabral identified in the 1960’s? Does increased investment in cashew value-added infrastructure address the priority long-term problems of Guinea Bissau? Does it not, in fact, make the people of Guinea Bissau even more dependent on a single crop?

And where do the profits go besides to the development banks? To answer this question, one must understand who owns the land and the farms. In Cashew cultivation in Guinea-Bissau – risks and challenges of the success of a cash crop the authors state,

“At the end of 1974, marking the end of the colonial era, several hundred hectares of cashew orchards had been planted, but no industrial processing of cashew nuts or apples was carried out. The amount of raw cashew available was still not enough to feed a decortication unit with a capacity considered economically viable at the time. Thus, the impetus for development of cashew gained during the 1960-74 period, was dampened in post-independence. However, some non-governmental organizations and cooperation agencies developed a relevant action using cashew in the context of forest interventions. The use of cashew trees as a cash crop, in forest protection schemes or as a way to recover soil fertility in fallows was stressed. Cashew was considered an important species to be used to restrain deforestation, because of its acceptability by the peasants. “

Here it should be noted that, according to some studies, the rate of deforestation has increased from about 2 percent per year between 1975 and 2000 to 3.9 percent over the 2000 to 2013 period. Overall, Guinea-Bissau lost about 77 percent of its forests between 1975 and 2013; only 180 sq km remain, mainly in the south near the Guinea border. Likewise, woodlands regressed by 35 percent over the 38 years, a loss of 1,750 sq km.

The authors of Cashew cultivation in Guinea-Bissau – risks and challenges of the success of a cash crop continue:

“A semi-manual decortication unit with a capacity of 250 tons per year and a bottling line for cashew apple juice and jams were built on Bolama Island in the late 1970’s with Dutch co-operation. Although this plant has proved to be economically unsustainable, its implementation was a strong boost to cashew cultivation.

By the mid-1980s, two factors gave new impetus to the intensity of planting and trading in the domestic market. The first was a non-organized race for the occupation of land by villagers, as a result of a significant increase in land grants to commercial farmers or "ponteiros" by government authorities. Since 1984, government policy aiming to increase agricultural production initiated large concession grants and, as of 1987, land distribution increased. It was estimated to represent around 300,000 ha out of an estimated agricultural area of 1,100,000 ha and 1,400,000 ha of silvo-pastoral land. These lands, contrary to what happens with traditional farmers, were demarcated and registered in the Land Registration Services of the Ministry of Public Works.

The gaps in the land property law, which overlooked customary rules that grant property rights to those who planted permanent crops, meant that traditional farmers tried to secure land to ensure their access to it. Cashew, due to its hardiness and quick growth, was an obvious choice. The second driving force was the authorities’ initiative to curtail cashew smuggling to Senegal, due to increased internal consumption and the revival of the cashew decortication factory in the Sokone province of that country. An informal barter trading practice was thus put in place, wherein cashew was exchanged for rice at a ratio of one to two, which evolved due to the relative change of the quotations of the two commodities to one to one. More recently, data from a country report for 2013 report a deterioration in the terms of trade, 1kg of rice being exchanged for up to 3 kg of cashew (Cont and Porto, 2014).

Another factor which can help to understand the continuous cashew expansion and consequent decrease in production of staple crops. It is the comparative advantage of cashew in terms of the differential days invested by cultural cycle and added value of the agricultural work invested per day. Since the traditional farmers’ strategy was to optimize work invested in agriculture, we can see a strong drive to shift from traditional agricultural practices to cashew cultivation. . . .

Cropping systems and cultivated varieties

Two main types of cropping systems co-exist in Guinea-Bissau: the peasant and the commercial system, locally known as "ponteiro". The vast majority of cashew orchards are owned by small farmers in villages all over the country. The average smallholder plantation is thought to cover 2-3 hectares, though farmers often have no idea of the size of their planted area.

The process of cashew expansion usually starts in the land closest to the center of villages and expansion follows a centrifugal trend. A piece of fallow land or semi-natural woodland or savanna woodland is prepared by cutting down the woody vegetation, which is burned by the end of the dry season. In the most frequently used system, cashew is intercropped in the first two or three years with food crops (e.g.: rainfed rice, millet, sorghum, maize or groundnuts). Every year a new piece of land can be prepared and sown with cashew and food crops. Cashew trees are sometimes also planted as live fences, despite the fact that their spreading habit makes them unsuitable for close spacing.

Plant spacing is traditionally very close (e.g.: 3-5 m), with roughly defined or even non-existent rows. However, in recent years this trend has begun to change, with greater plant spacing and the use of well-defined rows in the younger cashew orchards. Within the lines the trees are often paired because two seeds are sown per hole with the idea that at least one may survive. Farmers who sow close together often do so following the advice to sow a large number of trees and thin them later, which is a good proposition for rapid establishment of a crop, minimizing costs of weed clearing and avoiding severe development of termite colonies. Unfortunately, many farmers never get around to thinning the trees.

At the level of the small farmer there is no varietal selection and no care is taken in the establishment of orchards. There is also no support dispensed by the very weak structures of agricultural research and extension in the country. These orchards, owned and explored at the family level, are small, rarely exceeding a few hectares and growing with virtually no agro-chemical inputs.

To tackle some of the problems mentioned, in the 1990 decade the Trade and Investment Promotion Project (TIPS) included an extension component that promoted cashew planting seminars around the country, nursery establishment and post-harvest technologies. However, at the end of the project, no ministry took over the continuation and consolidation of the objectives. Therefore, only a minority of farmers had incorporated the knowledge made available.

At the "ponteiro" or commercial system level, a number of plantations are distributed throughout the country, with great heterogeneity in terms of size and care dispensed to the orchards. The orchards owned by small “ponteiros’ are established using a method similar to that of the traditional farmers, with no care for the choice of seeds and close tree spacing. Conversely, in a few agro-industrial farms whose extension surpasses 1000 hectares in some cases, care has been taken in the selection of parent material and in adequate tree spacing. Nevertheless, in both peasant and commercial systems no agro-chemical inputs were used in the cashew orchards. Thus, the Guinean cashew nuts are organic and can fetch a higher price if suitably processed and marketed, and comply with stringent hygiene standards as demanded by international markets. However, this is yet to be fulfilled. . . .

Cashew tree and land ownership

In Guinea-Bissau the land is formally considered state-owned but, as in most of West Africa, consuetudinary land tenure practices are linked to the planting of perennial plants, in particular fruit trees (Fenske, 2011). In times of increasing population density, and when the sale of land is becoming a common practice, cashew orchards can act as land tenure insurance (Temudo and Abrantes, 2012). In this respect, the cashew nut tree possesses several advantages: it is a rapid growing tree which does not require much care or manpower to establish and maintain and, above all, produces a non-perishable fruit with an assured market. On the other hand, cashew works like insurance for the elderly, in times of exodus of young males to the towns, because it requires little manpower that can be largely provided by women and children (Lundy, 2012). The role of cashew trees in the marking of land tenure can thus explain, to a certain extent, the success of the crop and is a matter that requires further study.

Trade, exportation and local processing of cashew

The outflow of annual production of cashew nuts occurs during the so-called "cashew campaign", which runs approximately from March-April to August. During this period, small free-lance buyers and officers of medium sized companies travel the country acquiring cashew nuts or exchanging them for rice.

From 2004 onwards, the cashew nut market became relatively liberalized and less dependent on rice bartering and more on a cash basis than previously. In approximate terms, the overall marketing chain from farm to port is quite short. There are up-country buyers acting on behalf of urban buyers; raw cashew nuts are delivered to town warehouses where they may be further dried, bagged and consolidated in loads, or sent directly to exporters in Bissau. Exporters may or may not re-bag the cashew nuts and then sell them to international dealers or processors for shipment to India. Participation in this chain of commercialization is licensed and each of the agents in the chain has to pay a fee to the Ministry of Commerce and the Chamber of Commerce, Industry and Agriculture (CCIA). As of 2004 there were about 300 registered buying agents and 40 exporters.

Fleeing from this general scheme, rural farmers maintain the custom of receiving a loan on rice on account of cashew nuts to produce the next season, often at an exchange ratio unfavorable for them. In years of low cashew nut production, this practice can have serious consequences for small farmers, specifically at the food security level.

The absence of a legislative and regulatory framework to structure the cashew market, a commodity that commands such importance to the country’s economy is surprising, and is a situation which should be remedied so that it can function with integrity and transparency of price formation and transactions. Without this market structuring, for which there are already positive examples in Africa, it is difficult to attain a fair partition of benefits for the majority of farmers.”

As per the Volza's Guinea Bissau Raw cashew nuts Exporters & Suppliers directory, there are 277 active raw cashew nuts exporters in Guinea Bissau exporting to 489 Buyers.

LION OVERSEAS PTE LTD accounted for maximum export market share with 146 shipments followed by DELTA STAR GENERAL TRADING LLC with 122 and OKI GENERAL TRADING LLC at the 3rd spot with 70 shipments.

ARREY AFRICA SARL is the largest cashew nut processor in the country. According to its website,

“Our company is located in Bula - Guinea Bissau. Arrey África has been operating a cashew nut processing plant with 5,000 m² of built area since 2015, and we have 225 employees.

In January 2021, we started the operation of another unit, in the same city, with twice the production capacity and forecast to hire 400 employees, with a built area of 7,000 m².

The Arrey Group also operates another factory in Brazil, EUROALIMENTOS, located in the city of Altos – Teresina/Piauí, with 400 employees and 15,000 m² of built area. For 25 years, it represents one of the most important industries in the state of Piauí.

Sustainability is part of one of our main goals; with this, we started the Bio project, through purchases from local cooperatives, where suppliers/producers are georeferenced, which demonstrates the origin and good practices of the products we process.

The AGRICERT certification gives us the right to guarantee the origin and qualty of our products.

Arrey África Company, together with the World Bank and the Private Sector Rehabilitation and Agroindustrial Development Support Project (PRSPDA), created a project within the cashew nut sector, directly linking farmers to the transformer in 2018.

The project has the help of 8 peasant cooperatives from two regions of the country (CACHEU and OIO).

In the same year of 2018, the orchards of 3,509 producers were georeferenced, and an area of 9987ha, which the Arrey Africa Company certified in organic cultivation through the Agricert certifier.

We have bio europa certificates, NOP, Haccp food safety certificate, and we are implementing the BRC, Smeta certificate… During the cashew nut season, Arrey África pays a bonus to the cooperatives, so that they are the ones who connect and transport the raw material from the producers to the factories, processing plants that Arrey has in the town of Bula, Comarca de Cacheu, where we process 4000MT of cashew nuts per year.

Arrey África this year 2022 will make available 6840m2 of its land in agreement with the city's school of agricultural technology for the cultivation of different vegetables and seedlings of the cashew nut tree for delivery to producers who join the project within the scope of improving the orchards of cashew.

Since 2015, our company has been exporting cashew nuts to several countries in Europe (Spain, France, Italy, Holland, Germany...), as well as the United States of America, Brazil and Asia.”

The Arrey Group includes Arrey Hotels, Arrey Construction, and Arrey Group Trade and Industry.

Alphonsa Cashew Industries, on its websites, states,

“The family has been in the cashew business since 1958. Alphonsa Cashew Industries was established as an independent business in 1986 by Babu Oommen under the patronage of his father and founder of the family business, Oommen Geevarghese. . . . Alphonsa is one of the largest direct procurers (on actual user basis) of Guinea Bissau raw cashew at the farm-gate level. . . . In line with our vision to vertically integrate our business and to create one of the most comprehensive traceability systems in the cashew industry, we started our Direct Procurement Programme in 2010 with our first procurement center being set up in Sampa, one of the most prominent cashews producing region in Ghana. This was followed by us expanding our direct sourcing footprint to Senegal, Côte d’Ivoire, Gambia, Tanzania and Guinea Bissau. What started as a single company has today grown to 12 independent companies, each lead by a descendant of the founding family, that is collectively one of the largest business group in the cashew industry.We began our direct procurement in 2019 with sourcing and shipping activities based out of Bissau, the capital of the country. . . . We have an ownership or active engagement in all stages of the cashew value chain starting from procurement of the highest quality raw cashew nut at the farm-gate level from 6 origins to in-house processing in 13 processing facilities in India and distribution of superior quality cashew kernels to over 300 customers spread across 43 countries worldwide. Cochin Chamber of Commerce, one of the most reputed Chamber of Commerce in India, ranks us among the top 10 shippers of cashew from India. . . .”

Guinean economist Aliu Soares Cassama has stated, “Our economy has had a deficit in the trade balance for a long time. In other words, we import more and export less. We know that economic agents do not have purchasing power due to the total paralysis of the State, and this situation will further complicate the economic weakness that the country is experiencing.”

AMILCAR CABRAL HAS TAUGHT US HOW THE ECONOMY OF GUINEA BISSAU DEVELOPED FROM A CASH CROP MONO-MERCANTALIST SYSTEM STARTED BY THE EXPORTS OF PEOPLE, THEN PEANUTS, NOW CASHEWS. THIS IS PROFITED FOREIGNERS AT THE EXPENSE OF GUINEANS.