[A]rmed revolt in the South became organized by the planters with the cooperation of the mass of poor whites. Taking advantage of an industrial crisis which throttled both democracy and industry in the the North, this combination drove the Negro back toward slavery. Finally, the poor whites joined the sons of the planters and disfranchised the black laborer, thus nullifying the labor movement in the South for a century and more. . . .

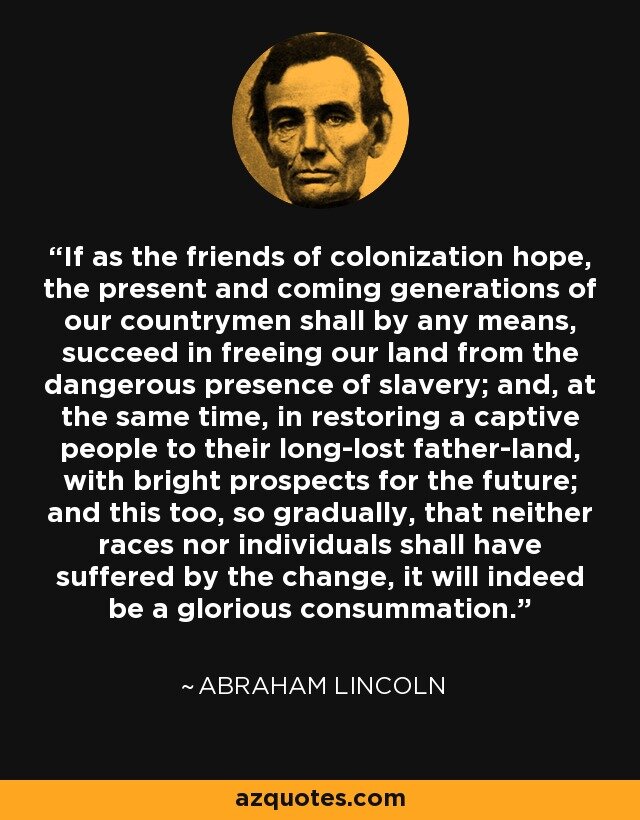

It is clear that from the time of Washington and Jefferson down to the Civil War, when the nation was asked if it was possible for free Negroes to become American citizens in the full sense of the word, it answered by a stern and determined ‘No!’ The persons who conceived of the Negroes as free and remaining in the United States were a small minority before 1861, and confined to (mis)educated free Negroes and some of the Abolitionists. [Note: more on Fredrick Douglass later]

This basic thought of the American nation now began gradually to be changed. It bore the face of fear. It showed a certain dismay at the thought of what the nation was facing after the war and under hypnotism of a philanthropic idea. The very joy in the shout of emancipated Negroes was a threat. Who were these people? Were we not loosing a sort of gorilla into American freedom? Negroes were lazy, poor and ignorant. Moreover, their ignorance was more than the ignorance of whites. It was a biological, fundamental and ineradicable ignorance based on pronounced and eternal racial differences. The democracy and freedom open and possible to white men of English stock, and even to Continental Europeans were unthinkable in the case of Africans. We were moving slowly in an absolutely impossible direction. . . .

The classic report on condition in the South directly after the war is that of Carl Schurz. Carl Schurz was of the finest type of immigrant Americans. A German of education and training, he had fought for liberal thought and government in his country, and when driven out by the failure of the revolution of 1848, had come to the United States, where he fought for freedom. No man was better prepared dispassionately to judge condition in the South than Schurz. . . . His mission came about in this way: he had written Johnson on his North Carolina effort at Reconstruction and Johnson invited him to call. . . . In his report, Schurz differentiated four classes in the South:

Those who, although having yielded submission to the national government only when obliged to do so, have a clear perception of the irreversible changes produced by the war, and honestly endeavor to accommodate themselves to the new order of things.

Those whose principal object is to have the states without delay restored to their position and influence in the Union and the people of the states to the absolute control of their home concerns. They are ready in order to attain that object to make any ostensible concession that will not prevent them from arranging things to suit their taste as soon as that object is attained.

The incorrigibles, who still indulge in the swagger which was customary before and during the war, and still hope for a time when the Southern Confederacy will achieve its independence.

The multitude of people who have no definite ideas about the circumstances under which they live and about the course they have to follow; whose intellects are weak, but whose prejudices and impulses are strong, and who are apt to be carried along by those who know how to appeal to the latter. . . .

In some localities, however, where our troops had not yet penetrated and where no military post was within reach, planters endeavored and partially succeeded in maintaining between themselves and the Negroes the relation of master and slave partly by concealing from them the great changes that had taken place, and partly by terrorizing them into submission to their behests. But side from these exceptions, the country found itself thrown into that confusion which is naturally inseparable from a change so great and so sudden. The white people were afraid of the Negroes, and the Negroes did not trust the white people; the military power of the national government stood there, and was looked up to, as the protector of both. . . .

I regret to say that views and intentions so reasonable I found confined to a small minority. Aside from the assumption that the Negro will not work without physical compulsion, there appears to be another popular notion prevalent in the South which stands as no less serious an obstacle in the way of a successful solution of the problem.

It is that the Negro exists for the special object of raising cotton, rice and sugar for the whites, and that it is illegitimate for him to indulge, like other people, in the pursuit of his own happiness in his own way. . .

The popular prejudice is almost as bitterly set against the Negro’s having the advantage of education as it was when the Negro was a slave. . . . Hundreds of times I heard the old assertion repeated, that ‘learning will spoil the nigger for work,’ and that ‘Negro education will be the ruin of the South.’ Another most singular notion still holds a potent sway over the minds of the masses - it is, that the elevation of the blacks will be the degradation of the whites. . . .

The emancipation of the slaves is submitted to only in so far as chattel slavery in the old form could not be kept up.

But although the freedman is no longer considered the property of the individual master, he is considered the slave of society, and all independent state legislation will share the tendency to make him such. The ordinances abolishing slavery passed by the conventions under the pressure of circumstances will not be looked upon as barring the establishment of a new form of servitude.

Carl Schurz summed the matter up:

“Wherever I go - the street, the shop, the house, the hotel, or the steamboat - I hear the people talk in such a way as to indicate that they are yet unable to conceive of the Negro as possessing any rights at all. Men who are honorable in their dealings with their white neighbors, will cheat a Negro without feeling a single twinge of their honor. To kill a Negro, they do not deem murder; to debauch a Negro woman, they do not think fornication; to take the property away from a Negro, they do not consider robbery. The people boast that when they get freedmen’s affairs in their own hands, to use their own expression, ‘the niggers will catch hell.’

The reason of all this is simple and manifest. the whites esteem the blacks their property by natural right, and however much they admit that the individual relations of masters and slaves have been destroyed by the war and by the President’s emancipation proclamation, they still have an ingrained feeling that the blacks at large belong to the whites at large.’

Corroboration of the main points in the thesis of Schurz came from many sources. From Virginia:

‘Before the abolition of slavery, and before the war, it was the policy of slaveholders to make a free Negro as despicable a creature and as uncomfortable as possible. They did not want a free Negro about at all. They considered it an injury to the slave, as it undoubtedly was, creating discontent among the slaves. The consequences were that there was always an intense prejudice against the free Negro. Now, very suddenly, all have become free Negroes; and that was not calculated to allay that prejudice.

A colored man testified:

‘There was a distinct tendency toward compulsion, toward reestablished slavery under another name. Negroes coming into Yorktown form regions of Virginia and thereabout, said that they had worked all year and received no pay and were driven off the first of January. The owners sold their crops and told them they had nor further use for them . . . .”

The courts aided the subjection of Negroes. George S. Smith of Virginia, resident since 1848, said that he had been in the Provost Marshal’s department and ‘have had great opportunities of seeing the cases that are brought before him. although I am prejudiced against the Negro myself, still I must tell the truth, and must acknowledge that he has rights. In more than nine cases out of ten that have come up in General Patrick’s office, the Negro has been right and the white man has been wrong, and I think that will be found to be the case if you examine the different provost marshals.’ . . .

Lieutenant Sanderson, who was in North Carolina for three years, said that as soon as the Southerners came in full control, they intended to put in force laws ‘not allowing a contraband to stay in any section over such a length of time without work; if he does, to seize him and sell him. In fact, that is done now in the county of Gates, North Carolina. The county police, organized under orders from headquarters, did enforce that. . . .

From Alabama it was reported:

‘The planters hate the Negro, and the latter class distrust the former, and while this state of things continues, there cannot be harmonious action in developing the resources of the country. Besides, a good many men are unwilling yet to believe that the ‘peculiar institution’ of the South has been actually abolished, and still have the lingering hope that slavery, though not in name, will yet in some form practically exist. . . .’

The New York Herald says of Georgia:

‘Springing naturally out of this discorded state of affairs is an organization of ‘regulators,’ so called. their numbers include many ex-Confederate cavaliers of the country, and their mission is to visit summary justice upon any offenders against the public peace. It is needless to say that their attention is largely directed at maintaining quiet submission among the blacks. The shooting or stringing up of some obstreperous ‘nigger’ by the ‘regulators’ is so common an occurrence as to excite little remark. Nor is the work of proscription confined to the freedmen only. The ‘regulators’ go to the bottom of the matter, and strive to make it uncomfortably warm for any new settler with demoralizing innovations of wages for ‘niggers.’’

A committee of the Florida legislature reported in 1865 that it was true that one of the results of the war was the abolition of African slavery.

‘But it will hardly be seriously argued that the simple act of emancipation of itself worked any change in the social, legal or political status of such of the African race as were already free. Nor will it be insisted, we presume, that the emancipated slave technically denominated a ‘freedman’ occupied any higher position in the scale of rights and privileges than did the ‘free Negro. If these inferences be correct, then it results as a logical conclusion, that all the arguments going to sustain the authority of the General Assembly to discriminate in the case of ‘free Negroes’ equally apply to that of ‘freedmen,’ or emancipated slaves.

But it is insisted by a certain class of radical theorists that the act of emancipation did not stop in its effect in merely severing the relationship of master and slave, but that it extended further, and so operated as to exalt the entire race and placed them upon terms of perfect equality with the whit man. These fanatics may be very sincere and honest in their convictions, but the result of the recent elections in Connecticut and Wisconsin shows very conclusively that such is not the sentiment of the majority of the so-called Free States.’

Judge Humphrey of Alabama said,

‘I believe in case of a return to the Union, we would receive political cooperation so as to secure the management of that labor by those who were slaves.

There is really no difference, in my opinion, whether we hold them as absolute slaves or obtain their labor by some other method. Of course, we prefer the old method, But that question is not now before us!’

A twelve-year resident of Alabama said:

‘There is a kind of innate feeling, a lingering hope among many in the South that slavery will be re-galvanized in some shape or other. They tried by their laws to make a worse slavery than there was before, for the freedman has not now the protection which the master from interest gave him before.

Every day, the press of the South testifies to the outrages that are being perpetrated upon un-offending colored people by the state militia. These outrages are particularly flagrant in the states of Alabama and Mississippi, and are of such character as to demand most imperatively the imposition of the national Executive. These men are rapidly inaugurating a condition of things - a feeling - among the freedmen that will, if not checked, ultimate in insurrection. The freedmen are peaceable and inoffensive; yet if the whites continue to make it all their lives are worth to go through the country, as free people have a right to do, they will goad them to that point at which submission and patience cease to be a virtue.

I call your attention to this matter after reading and hearing from the most authentic sources - officers and others - for weeks, of the continuance of the militia robbing the colored people of their property -arms - shooting them in the public highways if they refuse to halt when so commanded, and lodging them in jail if found from home without passes, and ask, as a matter of simple justice to an unoffedning and downtrodden people that you use your influence to induce the President to issue an order or proclamation forbidding the organization of state militia.’

In Mississippi:

“In respectful earnestness I must say that if at the end of all the blood that has been shed and the treasure expended, the unfortunate Negro is to be left in the hands of his infuriated and disappointed former owners to legislate and fix his status., God help him for his cup of bitterness will overflow indeed. . . .

Sumner quotes ‘an authority of peculiar value’ - a gentleman writing from Mississippi:

‘I regret to state that under the civil power deemed by all the inhabitants of Mississippi to be paramount, the condition of the freedmen in many portions of the country has become deplorable and painful in the extreme. I must give it as my deliberate opinion that the freedmen are today, in the vicinity where I am now writing, worse off in most respects than when they were held slaves.

If matters are permitted to continue on as they now seem likely to be, it needs no prophet to predict a rising on the part of the colored population, and a terrible scene of bloodshed and desolation. Nor can anyone blame the Negros if this proves to be the result.

I have heard since my arrival here, of numberless atrocities that have been perpetrated upon the freedmen. It is sufficient to state that the old overseers are in power again . . . .’

There was no inconsiderable number of Southerners who stoutly maintained that Negroes were not free. The Planters’ Party of Louisiana in 1864 proposed to revive the Constitution of 1852 with all its slavery features. They believed that Lincoln had emancipated the slaves in the rebellious pasts of the country as a war measure. Slavery remained intact within the Federal lines except as to the return of fugitives, and might be reinstated everywhere at the close of hostilities; or, in any case, compensation might be obtained by loyal citizens through the decision of the Supreme Court. . . .

The Houston, Texas, Telegraph was of the opinion that emancipation was certain to take place but that compulsory labor would replace slavery. Since the Negro was to be freed by the Federal Government solely with a view to the safety of the Union, his condition would be modified only so far as to insure this, but not so far as materially to weaken the agricultural resources of the country.

Therefore, the Negroes wold be compelled to work under police regulations of a stringent character.”

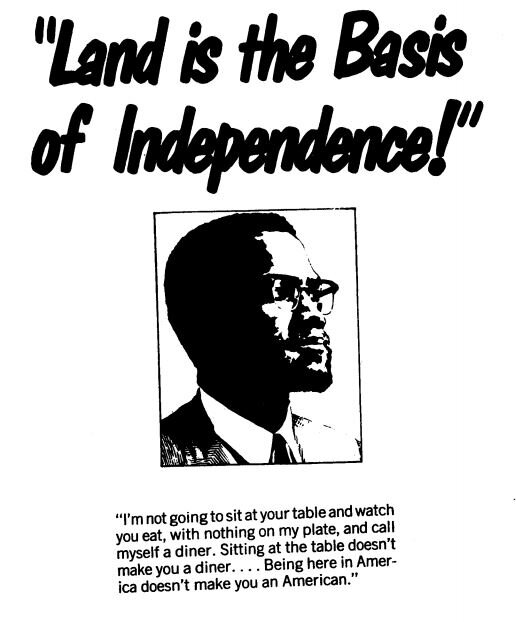

Therefore, it was a the combination of bitter planters and ex-Confederate soldiers, in an alliance with poor whites based on race and the community of white people, which stood opposed to the demand for LAND, be it a return to Africa or land in America and opposed to educating and informing the emancipated victim of trafficking from Africa and enslavement in America, that prevented the solution of American’s race problem at the end of the Civil War.

Also working against this was the co-optation of the legitimate and majority demand for LAND and INDEPENDENCE by Christianized Negroes, many of them biracial ‘mulatto’ offspring. Chief among them was Frederick Douglass. As as already been pointed out, Douglass’ contemporaries and peers overwhelmingly want to return to their ancestral lands or obtain their own land in American and become independent.

After escaping from slavery in Maryland, Douglass became a national leader of the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts and New York, gaining note for his oratory and incisive antislavery writings. In his time, he was described by abolitionists as a living counter-example to slaveholders' arguments that slaves lacked the intellectual capacity to function as independent American citizens. Douglass wrote several autobiographies. He described his experiences as a slave in his 1845 autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, which became a bestseller, and was influential in promoting the cause of abolition, as was his second book, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855). The feeling of freedom from American racial discrimination amazed Douglass:

Eleven days and a half gone and I have crossed three thousand miles of the perilous deep. Instead of a democratic government, I am under a monarchical government. Instead of the bright, blue sky of America, I am covered with the soft, grey fog of the Emerald Isle [Ireland]. I breathe, and lo! the chattel [slave] becomes a man. I gaze around in vain for one who will question my equal humanity, claim me as his slave, or offer me an insult. I employ a cab—I am seated beside white people—I reach the hotel—I enter the same door—I am shown into the same parlour—I dine at the same table—and no one is offended ... I find myself regarded and treated at every turn with the kindness and deference paid to white people. When I go to church, I am met by no upturned nose and scornful lip to tell me, 'We don't allow niggers in here!'

Louis Mehlinger, in The Attitude of the Free Negro Toward African Colonization, writes,

“To carry out more effectively the work of ameliorating the condition of the colored people, a National Council composed of two members chosen by election at a poll in each State, was organized in 1853. As many as twenty State conventions were to be represented. Before these plans could be well matured, however, those who believed that emigration was the only solution of the race problem called another convention to consider merely that question. Only those would not introduce the question of African emigration but favored colonization in some other parts, were invited. Among the persons thus interested were Reverend William Webb and Martin R. Delaney of Pittsburgh, Doctor J. Gould Bias and Franklin Turner of Philadelphia, Reverend August R. Greene of Allegheny, Pennsylvania, James M. Whitfield of New York, William Lambert of Michigan, Henry Bibb, James Theodore Holly of Canada, and Henry M. Collins of California.

Frederick Douglass criticized this step as uncalled for, unwise, unfortunate, and premature. . . . The greatest enemy of the Colonization Society among the freedmen . . . . was Frederick Douglass.

At the National Convention of Free People of Color, held in Rochester, New York, in 1853, Douglass was called upon to write the address to the colored people of the United States. A significant expression of this address was: ‘We ask that no appropriation whatever, State of national, be granted to the colonization scheme. ‘ . . . .[I]n writing to Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe in reply to her inquiry as to the best thing to be done for the elevation of the colored people, ‘The truth is,’ he said, ’we are here and here we are likely to remain. Individuals emigrate, nations never. We have grown up with this republic and I see nothing in her character or find in the character of the American people as yet, which compels the belief that we must leave the United States.’”

Hollis Lynch writes in Pan-Negro Nationalism in the New World Before 1862 that,

“Before Delany could act on his scheme, the largest Negro national conference up to that time was convened in Rochester, New York, in 1853, and the persistent division between emigrationists and anti-emigrationists was forced into the open.

The anti-emigrationists, led by the Negro leader Frederick Douglass, persuaded the conference to go on record as opposing emigration.

But as soon as the conference was over, the emigrationists, led by Delany, James M. Whitfield, a popular poet, and James T. Holly, an accomplished Episcopalian clergyman, called a conference for August 1854, from which anti-emigrationists were to be excluded. Douglass described this action as ‘marrow and illiberal,’ and

he sparked the first public debate among American Negro leaders on the subject of emigration.

Here Douglass is betraying the expressed desire (through songs) of his enslaved brothers and sisters who wanted to leave the United States and return to Africa. This either/or rejection of emigration was a major mistake made by Douglass and other Christianized Negroes.

At the opening of the Civil War, according to DuBois,

“Frederick Douglass spoke for the free and educated black man. . . .: ‘Events more mighty than men, eternal Providence, all-wise and all-controlling, have placed us in new relations to the government and the government to us. . . Citizenship is no longer denied us under this government. Under the interpretation of our rights by Attorney General Bates, we are American citizens. . we can import goods, own and sail ships and travel in foreign countries, with American passports in our pockets; and now, so far from there being any opposition, so far from excluding us from the army as soldiers, the President at Washington excluding us from the army as soldiers, the President at Washington, the Cabinet, and the Congress, the generals commanding and the whole army of the nation unite in giving us one thunderous welcome to share with them in the honor and glory of suppressing treason and upholding the star-spangled banner. . . .I hold that the Federal Government was never, in its essence, anything but a n antislavery government. Abolish slavery tomorrow, and not a sentence or syllable of the Constitution need be altered. It was purposely so framed as to give no claim, no sanction to the claim of property in man. If in its origin slavery had any relation to the government, it was only as the scaffolding to the magnificent structure, to be removed as soon as the building was completed. There is in the Constitution no East, no West, no North, no South, no black, no white, no slave, no slaveholder, but all are citizens who are of American birth. Such is the government, fellow-citizens, you are now called upon to uphold with your arms. Such is the government, that you are called upon to cooperate with in burying rebellion and slavery in a common grave. Never since the world began was a better chanse offered to a long enslaved and oppressed people. The opportunity is given us to be men. With one courageous resolution we may blot out the handwriting of ages against us. Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters U.S.; let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on earth or under the earth which can deny that he has earned the right of citizenship in the United States.”

Hollis Lynch writes in Pan-Negro Nationalism in the New World Before 1862 that,

“The emigrationist position was generally strengthened by the Dred Scott decision of 1857, which led directly to the founding of the Weekly Anglo-African and the Anglo-African Magazine by Robert Hamiltion, who in 1859 urged Negroes to ‘set themselves zealously to work to create a position of their own - an empire which shall challenge the administration of the world, rivaling the glory of their historic ancestors.

Events in the United States were continuing to give impetus to the emigration movement: the failure of John Brown’s raid, the split in the Democratic Party, and the founding of the avowedly anti-slavery Republican Party had both exacerbated feelings against Negroes and increased the interest in emigration. By January 1861, the Haitian emigration campaign seemed to be succeeding. . . . . Indeed, by 1861 almost all American Negro leaders had given some expression of support to Negro emigration. Even the formidable Frederick Douglass gave in and accepted an invitation by the Haitian government to visit the country. Thus, when Delany and Campell returned to the United States in Late December 1860, they found that the feeling for emigration was stronger than ever . . . ‘Africa is our fatherland, we its legitimate descendants, and we will never agree or consent to see this . . . step that has been taken for her regeneration by her own descendants blasted.’ . . .

When Blyden and Crummell returned to Liberia in the fall of 1861, they reported the support of American Negroes for emigration. The Liberian government decided to act: legislation was passed by which Blyden and Crummell were appointed commissioners ‘to protect the cause of Liberia to the descendants of Africa in that country, and to lay before them the claims that Africa had upon their sympathies, and the paramount advantages that would accrue to them, their children and their race by their return to the fatherland.

INDEED, WHEN IN THE SUMMER OF 1862 LINCOLN DECIDED TO PUT INTO EFFECT HIS SCHEME FOR GRADUAL NEGRO EMANCIPATION WITH COLONIZATION, HE RECEIVED NO SUPPORT FROM AMERICAN NEGRO LEADERS.

Thus when Blyden and Crummell returned to the United States as official commissioners in the summer of 1862, to urge American Negroes to ‘return to the fatherland,’ they found ‘an indolent and unmeaning sympathy - sympathy which put forth no effort, made no sacrifices, endured no self-denial, braved no obloquy for the sake of advancing African interests.’ Further, Lincoln’s proclamation of January 1, 1863, ending slavery, and the use of later in that year of Negro troops in the Union army, made American Negroes feel sure that a new day had dawned for them.

In this they were wrong, of course. Although Negroes were awarded political and civil rights during the period of Reconstruction (1867 -1877), their hopes of full integration within American society were largely frustrated. This disappointment, continuing throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, again resulted in a desire to leave for other parts of the Americas or for Africa.”

Miles Mark Fisher writes in “Deep River”,:

“The task of the colonizationists was yet incomplete. They had to supply Negroes with actual ships on the ocean, and they did so. Nine transport ships went to Liberia under the auspices of the American Colonization Society between 1827 and 1830. . . . Notwithstanding, its evolution was in conformity with what Negroes wanted, and its permanent organization to send Negroes outside the United States provided that it be ‘with their consent.’ Richard Allen, [Frederick Douglass] and William Lloyd Garrison should not be considered interpreters of the aspirations of Negroes to the neglect of colonizationists like Lott Cary and Jehudi Ashmun. Nineteenth-century North Americans were persuaded that free Negroes could not become better than they were in the United States.

FREE NEGROES AS WELL AS SLAVES WERE MISREPRESENTED.”

THUS, FREDERICK DOUGLASS LAUNCHED THE INTEGRATION MOVEMENT TO COUNTER THE DEMAND FOR LAND AND INDEPENDENCE.