The African Union and the African Diaspora - Tracking the AU 6th Region Initiative and the Right to Return Citizenship: A Resource for the 8th Pan African Congress Part 1 in Harare, Zimbabwe

WORKING PAPER ON DESIRABLE RESULTS OF THE 6TH PAN AFRICAN CONGRESS, TANZANIA 1974

————————————-

African charter oN HUMAN AND PEOPLES RIGHTS - 1981

Article 12

1. Every individual shall have the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of a State provided he abides by the law.

2. Every individual shall have the right to leave any country including his own, and to return to his country. This right may only be subject to restrictions, provided for by law for the protection of national security, law and order, public health or morality.

World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance - Durban Declaration, 31 August to 8 September 2001

“54. We underline the urgency of addressing the root causes of displacement and of finding durable solutions for refugees and displaced persons, in particular voluntary return in safety and dignity to the countries of origin, as well as resettlement in third countries and local integration, when and where appropriate and feasible;”

“78. Urges those States that have not yet done so to consider signing and ratifying or acceding to the following instruments:

(a) Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide of 1948;

(l) The Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court of 1998;”

Commentary: the 1949 Geneva Convention Article 4 (1) defines prisoners of war and Article 5 states,

“the present Convention shall apply to the persons referred to in Article 4 from the time they fall into the power of the enemy and until their final release and repatriation.”

The new Geneva Convention Protocol on Prisoners of War, which the United States has signed but not yet ratified and which went into force for some states on 7 December 1978, has provided in Articles 43 through 47 broader standards for prisoners of war, who come from irregular and guerilla units, than the terms of the 1949 Article 4. Article 45 of the 1978 Protocol states that a

“A person who takes part in hostilities and falls into the power of an adverse Party shall be presumed to be a prisoner of war… if he claims the status of war, or if he appears to be entitled to such status, or if the party on which he depends claims such status on his behalf.”

The African Diaspora, referred to as “Afrodescendents” has been determined by a competent tribunal -- the Third World Conference against Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance in the city of Santiago, Chile in the year 2000 - and confirmed in 2002 at the United Nations Conference for the Rights of Minorities in La Ceiba, Honduras to refer to the African Diaspora that

Were forcibly disposed of their homeland, Africa;

Were transported to the Americas and Slavery Diaspora for the purpose of enslavement;

Were subjected to slavery;

Were subjected to forced mixed breeding and rape;

Have experienced, through force, the loss of mother tongue, culture, and religion;

Have experienced racial discrimination due to lost ties from their original identity.

Thus, the designation or status of “prisoner of war” under the Geneva Convention is valid for Afrodescendants since they have yet to be repatriated to their land of origin.

“87. Urges States parties to adopt legislation implementing the obligations they have assumed to prosecute and punish persons who have committed or ordered to be committed grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 and Additional Protocol I thereto and of other serious violations of the laws and customs of war, in particular in relation to the principle of non-discrimination;”

“IV. Provision of effective remedies, recourse, redress, and other measures at the national, regional and international levels

158. Recognizes that these historical injustices have undeniably contributed to the poverty, underdevelopment, marginalization, social exclusion, economic disparities, instability and insecurity that affect many people in different parts of the world, in particular in developing countries. The Conference recognizes the need to develop programmes for the social and economic development of these societies and the Diaspora, within the framework of a new partnership based on the spirit of solidarity and mutual respect, in the following areas:

Facilitation of welcomed return and resettlement of the descendants of enslaved Africans;

160. Urges States to take all necessary measures to address, as a matter of urgency, the pressing requirement for justice for the victims of racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance and to ensure that victims have full access to information, support, effective protection and national, administrative and judicial remedies, including the right to seek just and adequate reparation or satisfaction for damage, as well as legal assistance, where required;

“168. Urges States that have not yet done so to consider acceding to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949 and their two Additional Protocols of 1977, as well as to other treaties of international humanitarian law, and to enact, with the highest priority, appropriate legislation, taking the measures required to give full effect to their obligations under international humanitarian law, in particular in relation to the rules prohibiting discrimination;”

First AU-Western Hemisphere Diaspora Forum in Washington, DC December 17-19, 2002

The Forum established the Western Hemisphere African Diaspora Network (WHADN) to interface with the African Union Commission. WHADN, which was given an 18 month mandate, put forward proposals for effective collaboration between the African Diaspora and the African Union which were refined by the AU Commission. One of those proposals, the Trade & Economic Development Committee proposed the following framework for recommendations as prerequisites to effective and meaningful participation in African trade and development by Africans in the western hemisphere Diaspora:

The African Union should consider the African Diaspora as Business partner, and

- Establish official programs to identify and qualify Diaspora businesses

- Issue a common visa, or eliminate business travel visas for Diaspora businesses.

IV. WORKING GROUP REPORTS

DEMOCRACY, GOVERNANCE AND THE RULE OF LAW

Selwyn R. Cudjoe (Chairperson)

Kwesi Addae,Lino D'Almeida,Carole Boyce-Davies,Cyril Boynes, Jr.,Howard Dodson,Earnie Ferreira,Tsita V. Himonyanga-Phiri,John W. Jackson,Michelle Jacobs,Kysseline Jean-Mary, Esq.,Dr. Nkamany Kabamba,Barbacar M'Bow, Mamabolo, Ibrahim Mohamed, Dr. Brimmy A.U. Olaghere, Kunirum Osia, Mohamed I. Shoush, Charles Kwalonu Sunwabe Jr., Yetunde Teriba, Barbara Tutani

“190. We, the participants of the above-named Working Group, move that the African Diaspora establishes itself for full regional representation at the African Union.”

The question of how to structure Diaspora representation was discussed, and it was agreed that the Western Hemisphere regions would be represented as follows:

i. Latin America (including Mexico and Central America)

ii. The Caribbean

iii. Brazil (given its language, size, and historical disconnect with the rest of Latin America)

iv. The United States

v. Canada (not grouped with the United States given the often different interests of the Diaspora of the two countries, as reported by members of the Working Group)

191. The question of citizenship was discussed extensively, and the following nonexclusive models were proposed:

i. Each Member-State legislate the right of citizenship to members of Diaspora,

ii. The African Union accords certain legal, civil and economic rights to members of the Diaspora,

iii. The African Union and Member-States declare all Africans in the Diaspora citizens of the New African Nation created, for the purpose of providing citizenship to people of descent. Through this process, members of the Diaspora will be accorded citizenship to the African Union, following the European Union model.

CLOSING REMARKS

Dr Jinmi Adisa, Senior Coordinator and Head of Conference on Security, Stability, Development and Cooperation (CSSDCA), Interim Commission of the African Union:

“236. We will take all your resolutions and recommendations to Chairman Essy and the Commission of the Union in Addis Ababa and through them to the Summit of the Union and while we may not be able to implement all of them immediately, you can be rest assured that they will eventually be reflected in the purposes, goals and programmes of the Union.”

RECOMMENDATION FOR COORDINATING BODY FOR AU-WESTERN HEMISPHERE DIASPORA

“December 19, 2002

250. The Meeting recommended that an office of the AU be established in Washington DC.

251. The meeting also recommended that the Foundation for Democracy in Africa serve as the coordinating body and be given the specific mandate to follow-up on the recommendations of the 1st AU-Western Hemisphere Diaspora Conference and work with the CSSDCA, enhancing the work of other African Diaspora NGOs internationally and in consultation with the AU Office in New York, within the next 18 months.”

CONSTITUTIVE ACT OF THE AFRICAN UNION (FEBRUARY 2003) AND PROTOCAL ON AMENDMENTS TO THE CONSTITUTIVE ACT OF THE AFRICAN UNION (JULY 2003)

On February 3-4, 2003, the first Extra-Ordinary Summit of the Assembly of the African Union meeting in Addis Ababa, Ehtiopia, adopted the historic Article 3(q) that officially, “invite(s) and encourage(s) the full participation of Africans in the Diaspora in the building of the African Union in its capacity as an important part of our Continent.” From this decision, the African Diaspora would become designated as the 6th Region of the African Union.” Article 3(q) was then adopted by the 2nd Ordinary Session of the Assembly of the Union in Maputo, Mozambique on July 11, 2003.

Decision on the Development of the Diaspora Initiative in the African Union at the Third Extraordinary Session in Sun City, South Africa May 2003

In May, 2003, the Executive Council of the African Union met at the Third Extraordinary Session in Sun City, South Africa and issued the "Decision on the Development of the Diaspora Initiative in the African Union" This decision stated in point 4 that it

"Supports the initiative of the Commission to convene a technical workshop, as soon as possible, to develop a concept paper to generate proposals on the relations between the AU and the Diaspora. The proposed workshop would also address the following issues:

- the definition of the Diaspora;

- the role of the Diaspora in reversing African brain drain in line with the NEPAD recommendations;

- the modalities of the creation of a Diaspora fund for investment and development in Africa;

- the modalities for the development of scientific and technical networks to channel the repatriation of scientific knowledge from the Diaspora to Africa, and the establishment of cooperation between those abroad and at home;

- the establishment of a Diaspora database to promote and facilitate networking and collaboration between experts in their respective countries of origin and those in the Diaspora.

The Decision also stated:

"b. What can the African Union offer the Diaspora?

Discussions during the Washington Forum also offers a picture of some of what the Diaspora may expect - a measure of credible involvement in the policy making processes, some corresponding level of representation, symbolic identification, requirements of dual or honorary citizenship of some sort, moral and political support of Diaspora initiatives in their respective regions, preferential treatment in access to African economic undertakings including consultancies, trade preferences and benefits for entrepreneurs, vis a vis non - Africans, social and political recognition as evident in invitation to Summits and important meetings etc. These deliberations must also focus on possibilities, criteria and qualification for Diaspora representation in the Economic, Cultural and Social Council (ECOSOC), the Pan-African Parliament, etc.

ASSEMBLY OF THE AFRICAN UNION Second Ordinary Session 10 - 12 July 2003 Maputo, MOZAMBIQUE: DECISION ON THE AMENDMENTS TO THE CONSTITUTIVE ACT - Doc. Assembly/AU/8(II) Add. 10 - July 10 -12, 2003 Maputo, Mozambique

African Union Technical Workshop on the Relationship With The Diaspora held in the Port of Spain, Trinidad, June 2-5 2004

Working Group 4: Modalities for enhancing effective partnerships between the African Union and the African Diaspora and Diaspora participation in ECOSOC

Recommendations included:

vi. The AUC should develop policies allowing the heads of state of Black nations outside the continent of Africa (in particular the Caribbean) to be included in the deliberations of AU Heads of State Summits and that, in turn, AU Heads of State representatives be invited to Summits of Black nations Heads of State outside of the continent of Africa. The same can be said for reciprocal invitations between African and African Diaspora meetings of professionals, trade associations, and trade unions. For instance, the AU would facilitate and coordinate the appointment of representatives of African professional associations to the executive councils of counterpart professional associations in Black nations and in nations with counterpart national and regional professional associations (both African descent associations and dominant professional associations with African descent caucuses) in areas such as law, medicine, the sciences (social and natural), engineering, the arts and humanities, media, urban planning, rural development, and education, etc.

vii. We recommend that the AU encourage representation policies for summits, conferences, workshops, and key meetings, which would allow for the coming together of government ministers within specified Diaspora Regions in areas of responsibility such as culture, labor, education, and trade to collaborate with AU counterpart ministers to address public policy matters of pressing concern in Diaspora regions and sub-regions (as has happened with the recent WTO meeting in Cancún). When and where appropriate, these meetings could include representatives from NGOs, private industries, professional associations, and civil rights movements.

ix. The AU Diaspora Initiative should establish criteria for selecting NGOs, private industries, universities, professional associations, and primary and secondary educational systems for partnership in the AU Diaspora Initiative. Regarding NGOs, this refers to the development of selection and evaluation criteria for the twenty NGO positions allotted in ECOSOCC. NGOs. Coalitions of NGOs interested in ECOSOCC representation, and which are recommended by regional secretariats to the AUC, must demonstrate capacity to design, implement, and evaluate services, projects, and programmes which (a) improve the quality of life of African and African Diaspora nations, communities, populations, and institutional sectors; or/and (b) promote education and awareness about African and African Diaspora history and other issues; and (c) establish collaborative partnerships with other NGOs, private industries, cultural organizations, Black social movements, and educational institutions. It is recommended that African Diaspora NGOs and coalitions of NGOs interested in being regional consultative partners with the African Union register with their respective regional secretariats;

all NGOs and coalitions of NGOs in the Western Hemisphere desiring to participate in the African Union Development of the Diaspora Initiative should register with WHADN as the first step of membership in this movement.

The AU should set other selection criteria reflecting its organizational needs and determine policy on issues such as length of tenure of ECOSOCC NGOs and NGO coalitions and criteria for renewal of tenure as set by formal performance evaluation procedures and standards.

xii. The AU should mandate Regional Diaspora Secretariats to coordinate and mobilize when needed Diaspora regional associations, organizations, and institutional sectors and to develop programmes to ensure their capacity to engage in partnerships with each other and with associations, organizations, and institutional sectors on the African continent.

xvi. The AU should consider offering Diaspora federal citizenship options and recommend that the AU establish a task force of distinguished scholars and policy makers to comprehensively study this question and offer policy recommendations to the AU Assembly.”

Report of the First Conference of Intellectuals of Africa and The Diaspora, October 6-9, 2004 in Dakar, Senegal

"59. The question on how to structure the Diaspora to make it as the 6th region was raised. To that effect:

- There is need to establish a representative body including the major regions of the world.

- 20 Diaspora organizations will be part of ECOSOCC, the advisory body of the African Union.

Recommendations

a) Setting up of an African experts group to serve as a 'think tank' to the AU.

e) Development of databases of associations to promote networking.

f) To promote the concept of African citizenship and the establishment of an African Passport.

87. Dr. Molefi Asante put forward five recommendations for the integration of the Diaspora and the continent. These include

i. the provision of curricula information from the African Diaspora in African schools,

ii. assigning responsibility to people in the ministries of African states to interface with the Diaspora

iii. operations from a perspective of strength rather than weakness,

iv. the need for African leaders to have precise knowledge of Diaspora communities as a basis for strengthening relations, and

v. the acceptance of the right of return for the African Diaspora.

Key issues and Recommendations

89. Five key issues were subject of recommendation. Preliminary discussions were held regarding the modalities for their implementation.

a. Creation of a specific structure of coordination as a follow up mechanism

i. The African Union should establish a Secretariat as a follow-up mechanism to engage in advocacy and to promote a permanent policy dialogue between intellectuals and policy makers in Africa and the Diaspora.

ii. The African Union should set up or adopt existing institutions to serve as 'Africa Houses' within strategic global and African locations to promote African interests abroad, improve awareness and knowledge about Africa, and support commercial and other links between the Diaspora and Africa.

c. Promotion of an African Citizenship Initiative

- In recognition of the importance of identity as a mobilizing factor for development, the African Union should develop a framework for a wider African Citizenship Initiative.

Modalities for Implementation

91. The African Union Commission should:

- Develop, in consultation with the Diaspora, proposals for a Bill of Citizenship that establishes rights, entitlements, and duties of African Citizens on the continent and in the Diaspora, including the responsibility of Member States and the African Union, and submit this to the Executive Council and Summit for consideration and approval.

c) Establishing The Diaspora as The Sixth Region of The African Union

- The Diaspora should initiate and, wherever it already exists should, broaden a process of consultation and regular meetings culminating in the establishment of transparent representative organs, to engage with the African Union.

Meeting of Experts on the Definition of the African Diaspora, April 11-12, 2005 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

VIII. ADOPTION OF THE DEFINITION OF THE AFRICAN DIASPORA

18. Following the discussion above, the meeting adopted the following definition by consensus as read by the Chairperson:

“The African Diaspora consists of peoples of African origin living outside the continent, irrespective of their citizenship and nationality and who are willing to contribute to the development of the continent and the building of the African Union.”

Siphiwe Note: this definition is severely flawed in light of the "Out of Africa" DNA studies. What is to stop a blonde-haired, blue-eyed Swede desiring to contribute to the development of Africa, for example, from claiming status as a member of the African Diaspora since current science states that his or her ancestors (and all human beings) originated in Africa? At the time, I recommended the following definition:

"The African Diaspora consists of peoples of African origin, descent and heritage living outside the continent, irrespective of their citizenship and nationality and who are willing to contribute to the development of the continent and the building of the African Union."

Under this definition, the Swede would be excluded on grounds that he or she did not possess an African heritage.

From Roots to Branches: The African Diaspora in a Union Government for Africa by Hakima Abbas January 2008

—————————————————————————————————————————-

DECISION ON THE FIRST AFRICAN UNION DIASPORA MINISTERIAL CONFERENCE - DOC. EX.CL/383(XII) - january 2008

The challenges of Diaspora representation in the African Union’s ECOSOCC Assembly Francis N. Ikome

The African Union Diaspora Initiative, Presentation by Dr. Jinmi Adisa, Director, Citizens and Diaspora Directorate, CIDO, African Union Commission, to the Annual Diaspora Consultation with Formations and Communities in North America, New York, USA, 21-22 October 2010

”Soon after the launching of the African Union in Durban, South Africa in 2002 therefore, the Assembly of Heads of States met in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia to establish, among other things, a legal framework that would create the necessary and sufficient conditions for putting this decision into effect. Hence, it adopted the Protocol on the Amendment to the Constitutive Act of the Union which in Article 3 (q) invited the African 4 Diaspora to participate fully as an important component in the building of the African Union. In adopting the decision, the Protocol symbolically recognized the Diaspora as an important and separate but related constituency outside the five established regions of Africa – East, West, Central North and South. Thus although there is no specific legal or political text that states this categorically, it, in effect, created a symbolic sixth region of Africa. . . .

DEFINITION OF THE AFRICAN DIASPORA

The meeting of Experts from Member States met in Addis Ababa, from 11-12 April 2005 and adopted the definition as follows: “The African Diaspora consists of peoples of African origin living outside the continent, irrespective of their citizenship and nationality and who are willing to contribute to the development of the continent and building of the African Union.” This definition was adopted at the next Ordinary Session of Council and Assembly in July 2005. The definition has attracted some criticisms. Though it was adopted by consensus, two delegations at the meeting felt strongly on the need for a two-part definition, one of which would capture the academic or intellectual aspects and the other that would be related to the political needs of the Union. Another delegation insisted on the need to add “permanently” to “ living outside the continent.” Thereafter, others have argued that the phrase “willingness to contribute to the development of the continent and the building of the African Union” should be left out. Nothing should be demanded or expected from the Diaspora. They should simply be recognized ipso facto as is the case with the Jewish and Israeli Diaspora. The criticisms are useful but they do not sufficiently address the complexity of the subject. The definition was arrived at after serious and deep reflection. The Experts agreed that any working definition must combine the following key characteristics as necessary and sufficient conditions.

A. Bloodline and/ or heritage: the Diaspora should consist of people living outside the continent whose ancestral roots or heritage are in Africa

B. Migration: The Diaspora should be composed of people of African heritage, who migrated from or are living outside the continent. In this context, three trends of migration were identified- pre-slave trade, slave trade, and post-slave trade or modern migration:

C. The principle of inclusiveness. The definition must embrace both ancient and modern Diaspora; and

D. The commitment to the African cause: The Diaspora should be people who are willing to be part of the continent (or the African family)

The AU definition comprises all these elements. A two-part definition would not be a working definition. Also, the distinction between the academic and political in this instance will be artificial. The AU is intrinsically a political and economic organization. Adding “permanently” before those “leaving outside” will imply that economic migrants or the modern African Diaspora would not be part of the working definition. This would be discriminatory and would also ignore an important and dynamic element of the Diaspora community. The final criticism regarding implied commitment of the Diaspora to rebuilding the African Union ignores the debate and decision of the Assembly of African Heads of States at the 1st Extra-Ordinary Summit of the Union in January 2003 which allied the Diaspora project to the building of the Union. This is not to imply that the AU definition of the African Diaspora is written in stone. It is a working definition and working definitions can be revised or improved upon if there are ample justifications for it. The Diaspora Initiative would always be work in progress and any work in progress would involve refinements of working models. . . .

Our organizational approach is to enable the Diaspora to organize itself with AU support within the framework provided by executive organs of the Union, the Council and Assembly and with guidance of Member States of the Union within these organs. The approach has not been without its difficulties. The Diaspora programme has created a phenomenon of rising expectations among the family abroad. This is laudable because it proves commitment. Yet, there are obvious signs of impatience. Moreover, civil society formations have not fully appreciated the organizational demands and imperatives of the AU. More often than not, the AU Commission is the whipping board for associated anger and frustrations. This is a burden that we are happy to bear.

More disturbing still is that there is some competition for power and influence within the Diaspora communities. This is a normal human disposition except that we see tendencies that can prove disruptive and which we must all try to rise above. There are some elements of the Diaspora within the US that wish to assume the natural leadership of the Diaspora agenda and to organize and centralize the Diaspora effort.

Discussions at the Expert Workshop in Trinidad and Tobago provided clear evidence that such apparent paternalism would undermine the general effort.

The challenge of organizing the Diaspora movement must embrace the need for autonomous regional coalitions to evolve and federate, if willing, but only by consent, at hemispheric levels, as may be deemed appropriate. The success of the Diaspora initiative, (to be assured) must dissuade focus on power blocs and stress an organizing principle based on democracy, within and among regions. . . .

At the continent – Diaspora level, the focus must be on building bridges across the Atlantic with an organizational emphasis on commitment, common cause and reciprocal advantages. The Commission and the Union must encourage the formation and consolidation of cooperative structures for mutual collaboration as inputs for the next wider Pan-African Congress.

Declaration of the Global African Diaspora Summit south africa 2012

”In the area of political cooperation, we commit to the following:

h) Strengthen the participation of the Diaspora population in the affairs of the African Union so as to enhance its contributions towards the development and integration agenda of the continent;

j) Encourage African Union Member States to urgently ratify the Protocol on the Amendments to the Constitutive Act, which, inter alia, invites the African Diaspora, an important part of our continent, to participate in the building of the African Union;

k) Encourage the Diaspora to organize themselves in regional networks and establish appropriate mechanisms that will enable their increasing participation in the affairs of the African Union as observers and eventually, in the future, as a sixth region of the continent that would contribute substantially to the implementation of policies and programmes.

n) Support efforts by the AU to accelerate the process of issuing the African Union passport, in order to facilitate the development of a transnational and transcontinental identity;

IMPLEMENTATION AND FOLLOW-UP

We adopt the following implementation and follow-up mechanism/strategy:

8. Agree to set up a Diaspora Advisory Board, which will address overarching issues of concern to Africa and its Diaspora such as reparations, right to return and follow up to WCAR Plan of Action, amongst others;

The African Union’s diplomacy of the diaspora: Context, challenges and prospects

AU 50th ANNIVERSARY SOLEMN DECLARATION may 2013

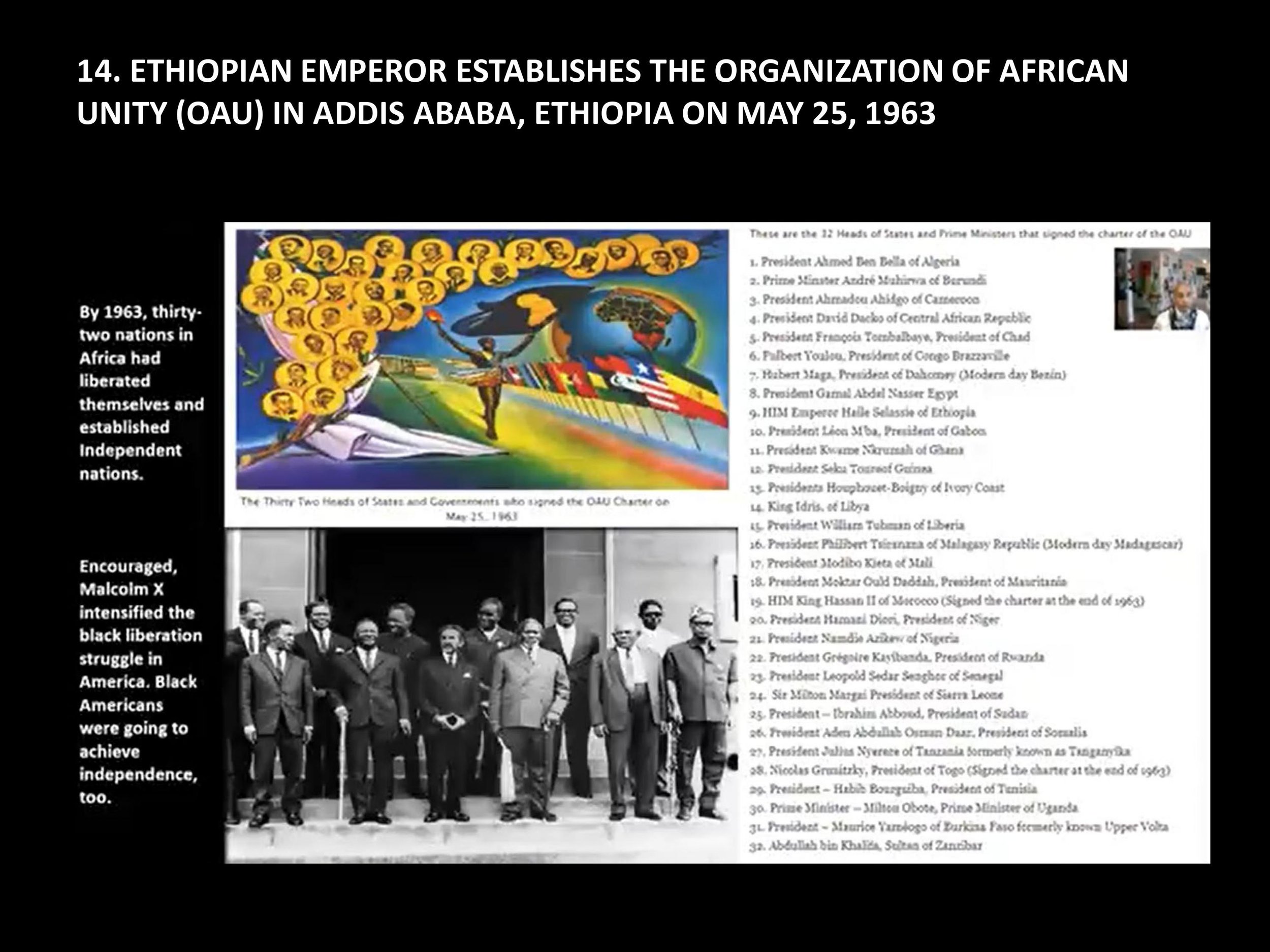

We, the Heads of State and Government of the African Union assembled to celebrate the Golden Jubilee of the OAU/AU established in the city of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia on 25 May 1963,

Evoking the uniqueness of the history of Africa as the cradle of humanity and a centre of civilization, and dehumanized by slavery, deportation, dispossession, apartheid and colonialism as well as our struggles against these evils, which shaped our common destiny and enhanced our solidarity with peoples of African descent;

Recalling with pride, the historical role and efforts of the Founders of the Pan African Movement and the nationalist movements, whose visions, wisdom, solidarity and commitment continue to inspire us;

Reaffirming our commitment to the ideals of Pan-Africanism and Africa’s aspiration for greater unity, and paying tribute to the Founders of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) as well as the African peoples on the continent and in the Diaspora for their glorius and successful struggles against all forms of oppression, colonialism and apartheid; . . . .

Stressing our commitment to build a united and integrated Africa;

Guided by the vision of our Union and affirming our determination to “build an integrated, prosperous and peaceful Africa, driven and managed by its own citizens and representing a dynamic force in the international arena”; . .

Guided by the principles enshrined in the Constitutive Act of our Union and our Shared Values . . . .

ACKNOWLEDGE THAT: . . .

III. The implementation of the integration agenda; the involvement of people, including our Diaspora in the affairs of the Union; the quest for peace and security. . . remain challenges.

WE HEREBY DECLARE:

A. On the African Identity and Renaissance

i) Our strong commitment to accelerate the African Renaissance by ensuring

the integration of the principles of Pan Africanism in all our policies and

initiatives;

ii) Our unflinching belief in our common destiny, our Shared Values and the

affirmation of the African identity; the celebration of unity in diversity and the

institution of the African citizenship;

iii) Our commitment to strengthen AU programmes and Member States

institutions aimed at reviving our cultural identity, heritage, history and Shared

values, as well as undertake, henceforth, to fly the AU flag and sing the AU

anthem along with our national flags and anthems;

iv) Promote and harmonize the teaching of African history, values and Pan

Africanism in all our schools and educational institutions as part of advancing

our African identity and Renaissance;

v) Promote people to people engagements including Youth and civil society

exchanges in order to strengthen Pan Africanism.

B. The struggle against colonialism and the right to self-determination of

people still under colonial rule

i) The completion of the decolonization process in Africa; to protect the right to

self-determination of African peoples still under colonial rule; solidarity with

people of African descend and in the Diaspora in their struggles against racial

discrimination; and resist all forms of influences contrary to the interests of the

continent; . . .

C. On the integration agenda

Our commitment to Africa‟s political, social and economic integration agenda, and in this

regard, speed up the process of attaining the objectives of the African Economic

Community and take steps towards the construction of a united and integrated Africa.

Consolidating existing commitments and instruments, we undertake, in particular, to:

i) Speedily implement the Continental Free Trade Area; ensure free movement

of goods, with focus on integrating local and regional markets as well as

facilitate African citizenship to allow free movement of people through the

gradual removal of visa requirements;

ii) Accelerate action on the ultimate establishment of a united and integrated

Africa, through the implementation of our common continental governance,

democracy and human rights frameworks. Move with speed towards the

integration and merger of the Regional Economic Communities as the building

blocks of the Union.

Global African Stakeholders Diaspora Convention, Washington DC, 19- 22 November 2015

DECISION ON FREE MOVEMENT OF PERSONS AND THE AFRICAN PASSPORT AT THE 27th Ordinary Session in Kigali, Rwanda in July 2016

Protocol to the Treaty Establishing the African Economic Community Relating to Free Movement of Persons, Right of Residence and Right of Establishment at the 29th Ordinary Session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government held in Addis Ababa in January/February 2018

“REITERATING our shared values which promote the protection of human and people’s rights as provided in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 and the African Charter on Human and Peoples Rights which guarantees the right of an individual to freedom of movement and residence;

GUIDED by our common vision for an integrated, people-centered and politically united continent and our commitment to free movement of people, goods and services amongs the Member States as an enduring dedication to Pan Afrianism and African integration as reflected in Aspiration 2 of the African Union Agenda 2063;

RECALLING our commitment under article 4(2)(i) of the Treaty Establishing the Econmic Community, to gradually remove obstacles to the free movement of persons, goods, services and capital and the right of residence and establishment among Member States:” [Siphiwe note: Here should be inserted, FURTHER RECALLING Article 3(q) to the Constitutive Act of the African Union to ““invite(s) and encourage(s) the full participation of Africans in the Diaspora in the building of the African Union in its capacity as an important part of our Continent.” ]

NOTING FURTHER the decision of the Peace and Security Council adopted at its 661st meeting (PSC/PR/COMM.1 (DCLX) held on 23rd February 2017 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia where the Council acknowledged that the benefits of free movement of people, goods and services far outweigh the real and potential security and economic challenges that may be perceived or generated;

REAFFIRMING our belief in our common destiny, shared values and the affirmation of the African identity, the celebration of unity in diversity and the institution of the African citizenship as expressed in the Solemn Declaration of the 50th Anniversary adopted by the 21st Ordinary Session of the Assembly of Heads of State and Government in Addis Ababa on 23rd May, 2013;

MINDFUL of the decision of the Assembly adopted in July 2016 in Kigali, Rwanda (Assembly?AU/Dec.607(XXVII) welcoming the launch of the African Passport and urging Member States to adopt the African Passport and to work closely with the African Union Commission to facilitate the processes towards its issuance at the citizen level based on international , continental and citizen policy provisions and continental design and specifications:

HAVE AGREED as follows:

Article 3 PRINCIPLES

The free movement of persons, right of residence and right of establishment in Member States shall be guided by the principles guiding the African Union provided in article 4 of the Constittutive Act.

Article 5 PROGRESSIVE REALIZATION

The free movement of persons, right of residence and right of establishment shall be achieved progressively through the following phases:

(a) phase one, during which States Parties shall implement the right of entry and abolition of visa requirements;

(b) phase two, during which States Parties shall implement the right of residence;

(c) phase three, during which States Parties shall implement the right of establishment

Article 10 AFRICAN PASSPORT

States Parties, shall adopt a travel document called “African Passport” and shall work closely with the Commission to facilitate the processes towards the issuance of this Passport to their citizens.

The Commission shall provide technical support to Member States to enable them to produce and issue the African Passport to their citizens.

The African Passport shall be based on international, continental and national policy provisions and standards and on a continental design and specifications.

Article 16 RIGHT OF RESIDENCE

Nationals of a Member State shall have the right of residence in the territory of any Member State in accordance with the laws of the host Member State.

A national of a Member State taking up residence in another Member State may be accompanied by a spouse and dependants.

States Parties shall gradually implement facourable policies and laws on residence for nationals for nationals of other Member States.

AGREEMENT ESTABLISHING THE AFRICAN CONTINENTAL FREE TRADE AREA - MARCH 21, 2018

CONCEPT NOTE African Union Continental Symposium on the Implementation of the International Decade for People of African Descent 18-20 September 2018 Accra/Cape Coast, Ghana

”The African Union Designation of the African Diaspora as the 6th Region of Africa The African Union Commission through its Citizens and Diaspora Directorate (CIDO) has instituted a program of Regional Consultative Conferences (RCCs) as a vehicle to enable the African Union to consult with the various Diaspora stakeholders around the world to give practical meaning to the designation of the African Diaspora as the 6th Region of the continent. Through this mechanism, CIDO has established and/or supported a growing number of AUaffiliated diaspora networks around the world, including in the Caribbean, Canada, Australia and Europe.”

Resolution on Africa’s Reparations Agenda and The Human Rights of Africans In the Diaspora and People of African Descent Worldwide - ACHPR/Res.543 (LXXIII) 2022

Dec 12, 2022

The African Commission on Human and People’s Rights, meeting at its 73rd Ordinary Session held in Banjul, The Gambia, from 21 October 2022 – 9 November 2022.

Recalling its mandate to promote and protect human and peoples' rights in Africa under Article 45 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights (the African Charter);

Recalling also the decision of the Assembly of the African Union to invite and encourage the full participation of the African diaspora as an important part of the Continent, in the building of the African Union;

Noting the commitment of members states in the African Union Diaspora Programme of Action of: (a) engaging developed countries with a view to creating favourable regulatory mechanisms governing migration, and to address concerns of African immigrants in diaspora communities; (b) working for the full implementation of the Plan of Action of the United Nations World Conference against racism; (c): engaging developed countries to address the political and socio-economic marginalization of diaspora communities in their country of domicile; and (d): strengthening the implementation of legislation and other measures aimed at eradicating child trafficking, human trafficking, child labour, exploitation of women and children in armed conflicts and other modern forms of slavery.

Reaffirming the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action as a comprehensive framework addressing racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia, and related intolerance;

Acknowledging the significance of the International Decade for People of African Descent (2015 – 2024) in advancing recognition, justice and development of people of African descent worldwide;

Reaffirming the obligations of States under the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights and relevant international human rights instruments, in particular the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination;

Recognizing that the human rights situation of Africans in the diaspora and people of African descent worldwide remains an urgent concern;

Expressing concern that Africans and people of African descent continue to suffer systemic racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance and other violations of their human rights;

Noting the emergence of contemporary forms of enslavement of Africans and people of African descent globally including in the Middle East and Arabo-Persian Gulf states;

Affirming that accountability and redress for legacies of the past including enslavement, the trade and trafficking of enslaved Africans, colonialism and racial segregation is integral to combatting systemic racism and to the advancement of the human rights of Africans and people of African descent;

Taking note of the ongoing discussions the calls from the African continent and Africa’s diaspora for reparations for legacies of the past including the trade and trafficking of enslaved Africans, colonialism and racial segregation;

Welcomes the reports of the United Nations Working Group of experts on people of African descent and its recommendations to eliminate racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance faced by people of African descent and Africans in the diaspora;

Welcomes also the recommendation by the Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent that work begins urgently to conceptualize Africa’s Reparations Agenda, seek the truth, define the harm, address the legacies of past tragedies, pursue justice and reparations and contribute to non-recurrence and reconciliation of the past;

The Commission:

1. Reinforces its collaboration with the Working Group of Experts on People of African Descent and other United Nations special procedure mechanisms concerning the human rights situation of Africans in the diaspora and people of African descent worldwide in the framework of the Addis Ababa Road Map.

2. Calls upon member states to:

promote and protect the human rights of African migrant workers worldwide including in the Middle East and Arabo-Persian Gulf states;

protect the human rights of migrants and ensure the right of all its citizens to receive full and authentic information about migration;

take measures to eliminate barriers to acquisition of citizenship and identity documentation by Africans in the diaspora;

to establish a committee to consult, seek the truth, and conceptualise reparations from Africa’s perspective, describe the harm occasioned by the tragedies of the past, establish a case for reparations (or Africa’s claim), and pursue justice for the trade and trafficking in enslaved Africans, colonialism and colonial crimes, and racial segregation and contribute to non-recurrence and reconciliation of the past;

respect their obligations under the International Convention on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, the Durban Declaration and Programme of Action, and the Programme of Activities for the Implementation of the International Decade for People of African Descent;

fulfill their commitment under the African Union Diaspora Programme of Action to encourage and support its adoption and implementation, in different diaspora countries, policies that facilitate the elimination of racism and the promotion of equality of all races.

3. Invites civil society to document and report on human rights cases concerning people of African descent and Africans in the diaspora (or AU sixth region) including migrants in the Middle East and Arabo-Persian Gulf states.

4. Encourages civil society and academia in Africa, to embrace and pursue the task of conceptualising Africa’s reparations agenda with urgency and determination.

Done in Banjul, The Gambia, on 9 November 2022